In 2015, during a visit to Lahore, curator Natasha Ginwala had the chance to meet the late Lala Rukh, even visiting her home studio. The experience, she says, was “life changing”.

To see the workspace of one of Pakistan’s most influential artists was a rare privilege. Ginwala was a mere window away from the garden where the Women’s Action Forum and other feminist movements in Lahore met in secret during the 1980s, developing printmaking techniques and producing materials that were considered subversive to the prevailing censorship laws and military rule. Her visit was a cerebral brush with Pakistan’s modern history.

What was even more invigorating, however, was the chance to hear from Rukh herself about both her art and her activism – aspects of her work she often kept independent from one another.

Ginwala had visited Rukh while preparing for Documenta 14, a 2017 contemporary art exhibition that took place in Germany and Greece. The curator hoped to touch upon not only Rukh’s art but her efforts as an activist. Speaking to Rukh was integral to knowing how to bridge the two elements of the artist’s output.

Ginwala had visited Rukh’s home with a mutual friend, writer and activist Urvashi Butalia. It was perhaps Butalia’s presence that gave Rukh a sense of comfort to openly discuss the disparate facets of her work.

“She was a bit more free in talking both about her activism and her art making, which usually she would keep separate,” Ginwala says. “Within the context there, she was much more open to kind of bringing these aspects together.

“I wanted to know about both those aspects. She’s not one of those artists who claim to be an activist. She actually just did this as a way of life.”

Ginwala met Rukh just before the artist died of cancer in 2017. “I met her at the very end of her life, which was also a very kind of emotional thing,” Ginwala says. Over the years, Ginwala has come to appreciate the “urgency” of that meeting, and it has since become a “central experience” in the curator’s life.

It is also the bedrock of Ginwala’s curatorial approach for Lala Rukh: In the Round.

The exhibition at Sharjah Art Foundation reflects this in the way it touches upon Rukh’s legacy not just as an artist, but as an educator and activist. It is curated by Sheikha Hoor Al Qasimi, director of Sharjah Art Foundation, as well as Ginwala, who is the artistic director of Colomboscope, a contemporary arts festival in Colombo. Ginwala has also been named one of the curators of Sharjah Biennial 16, slated to run from February to June 2025.

Rukh’s art, through videos, photographs and drawings, exhibits an almost serene familiarity with the nuances of light and time, and how the two work together to manifest transient beauties in a landscape.

Many in the UAE may be familiar with her art. Her works were featured at the Sharjah Biennial 12, giving insights to how the artist contemplated time in philosophical as well as visual dimensions. Rukh also participated at Sharjah’s March Meeting in 2015.

During her session, she spoke about she developed a screen printing manual in her own garden. The manual was an act of resistance designed to defy a ban on printing and circulating materials that were considered disruptive by the marshal law regime of Pakistan’s General Zia. Rukh also had her first solo exhibition in Dubai in 2017, presenting at Grey Noise gallery.

However, each of these events addressed one side to Rukh’s multifaceted output. As such, In the Round offers a more holistic glimpse of who Rukh was, across various fields. This makes the exhibition an unprecedented survey of an artist who was spectacular for many reasons.

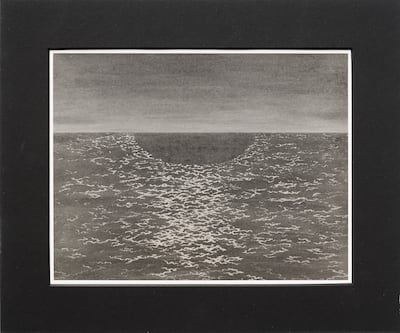

Lala Rukh: In the Round sprawls across three galleries at the Mureijah Art Spaces. It unfolds with several stunning pieces from Rukh’s oeuvre, including Moonscape, a series of triptychs produced using graphite and carbon paper. The works present Rukh’s deft approach to capturing light by depicting a single scene across three different moments in time.

Details including clouds and ripples shimmer in and out of view as viewers change their vantage point. Each piece within the triptychs measures at 28cm by 21.5cm. Being relatively small in size, the pieces invite the viewer to come gradually closer, revealing novel landscapes with every step.

This ability to goad out landscapes from within landscapes is explicitly underscored in Rukh’s River In An Ocean. In this series, Rukh reveals shifting curves and patterns within landscapes. Serpentine bends of light glisten over calm oceanic landscapes.

Sunlight streams over currents giving the impression of a grassy field. Shadows from clouds fall over otherwise brilliantly illuminated waterscapes with a beauty that verges on abstraction. The works give the impression that they are seen from an aeroplane window and were produced after the artist visited Peshawar in the early 1990s.

“There’s a lot of talk about the role of time in an artistic practice. There are many artists who are also seen as timekeepers,” Ginwala says. Rukh was an embodiment of this ethos in more ways than one.

The artist’s preoccupation with time can also be seen in the works that revolve around music. In her Hieroglyphics series, Rukh notates Hindustani classical rhythms in unique visual patterns. The works employ calligraphic elements, going left to right with dotted patterns and with a grace that touches upon time, space and rhythm.

Music had a foundational role in Rukh’s practice. Both of Rukh’s parents were deeply involved with Pakistan’s cultural scene. While her mother studied Punjabi Sufi Poetry, Rukh’s father was a major patron of Lahore’s art and classical music.

In the late fifties, Hayat Ahmad Khan founded the All Pakistan Music Conference. It was a time when classical music education and functions were waning in Pakistan, and Khan sought to revitalise the art form. Rukh was an active volunteer in the conference. There is a special section within In the Round dedicated to the conference, with photographs, as well as a majlis seating area, where visitors can listen to recordings of the performances.

“I was really drawn to this aspect of Rukh’s work because a lot of my a lot of my curatorial work looks at rhythm structures and how artists respond to rhythm,” Ginwala says.

“This relationship that she had, not just with the passage of time, but really with the role of music, and the in-depth understanding of sound, which came from her father. She [intrinsically] had it but it grew because she was constantly sitting in on these concerts, meeting incredible musicians, contributing to that sophistication of understanding rhythm, form, structure, timekeeping.”

Then comes perhaps one of the most inspiring phases of Rukh’s career. In the 1980s, shortly after returning from Chicago, where she had gone to study, Rukh joined the art faculty of the University of the Punjab. Around the same time, she cofounded the Women’s Action Forum, along with 15 other cultural figures, including journalist Najma Sadeque and author Nighat Said Khan. The forum was dedicated to bolstering women’s legal rights and equality in the face of Zia ul-Haq’s regime.

Rukh also cofounded Simorgh, a feminist collective that aimed to research and produce publications that highlighted women’s issues. It is through this collective that Rukh developed In Our Own Backyard – a manual that democratised screen printing techniques and became a pivotal resource for spreading feminist ideas in Pakistan. Rukh held workshops to help women develop printmaking skills in her garden.

The exhibition details this phase with Rukh’s political posters, photographs of the workshops, as well as images documenting various events that researchers are only just beginning to pinpoint and understand the significance of.

There are images of art workshops in Sri Lanka, dance and theatre performances, as well as children’s art therapy initiatives following an earthquake. Many of the images aren’t accompanied by captions, as details about what they document are still somewhat murky, but they nevertheless provide a sharp insight with Rukh’s involvement with communities across South Asia.

In many ways, Rukh’s legacy is still being unfolded and this section of the exhibition is a testament to that. The exhibited photographs come from an archive that has been meticulously preserved and digitised by Rukh’s niece, Maryam Rahman, who is an artist herself.

“She’s in charge of the estate of Lala, and the archive. She grew up with Lala, and she was Maryam’s creative influence,” Ginwala says, adding that Rahman also set out to document perspectives of others who were familiar with Rukh’s practice.

The exhibition contains several of these interviews. The videos and audio recordings feature artists and creative practitioners who worked with Rukh or studied under her at Lahore’s National College of Arts, where she taught until her retirement in 2012.

“This material has not been shared in this way,” Ginwala says. “I’m sure it will multiply and there’ll be even bigger presentations in the future, but at this point, it is the first time that it is being publicly shared.”

From her pensive landscape works to the sharply specific posters and initiatives that advocate for women’s rights, Lala Rukh: In the Round provides a sharp and holistic insight to an artist who was well ahead of her time. Though Rukh has exhibited around the world in her lifetime, the breadth of her artistic legacy is only just beginning to be truly examined and appreciated.

“I’m really grateful that this exhibition,” Ginwala says. “It became a beautiful meeting point for a lot of people who have already upheld and built Rukh’s legacy and that carry the values that she embodied. The exhibition examines all of these different facets, and connects her to larger conversations, global and local.”

Ginwala says she is particularly proud that the exhibition is happening in Sharjah. “There’s a lot of gratitude from a lot of South Asian community members in the UAE,” she says. “It is very recent for South Asian voices to be present for their own value and their own histories, not only because they carry Gulf history within them and their story.”

Lala Rukh: In the Round is running at Sharjah Art Foundation until June 16

Updated: June 09, 2024, 3:04 AM