Posted In:

Hromadske Radio, ,

Culture,

Visual Arts,

The program’s guest, art critic and translator Diana Klochko, discusses the outstanding ceramicist Olga Rapay-Markish.

Diana Klochko: I got to talk to Olga Rapay-Markish thanks to Leonid Finberg, who invited me to her studio as we prepared an album/book about her. I was not just stunned. I was in permanent delight arising from her artistic space and our interaction. I could take any of her works into my hands. I was also impressed by how she later reacted to the text I wrote for this book.

These are several layers of communication. Absolutely unique communication that I often recall. All my books have to do with Rapay-Markish one way or another.

In conversation with her, I learned about the fate of her parents. I started reading the poetry of her father, Peretz Markish, and learned why she was also attached to French culture, particularly French modernism. I began to discover for myself the Ukrainian-Jewish-French trinity of her images. The reason was that her father was a friend of the Parisian modernists of the early 20th century.

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: As far as I know, her father lived in Paris for some time.

Diana Klochko: Yes. Ukrainians are now discovering how prominently Ukrainian artists are featured in Parisian affairs. There is an entire constellation of artists from Odesa who produced art nearby in the same context of modernism.

Olga Rapay-Markish and her works

Diana Klochko: Olga Rapay-Markish was born Golda. There was also a history of identity change, initially forced and then voluntary. Even though she divorced the outstanding sculptor Mykola Rapay, she warmly remembered her mother-in-law. This is also a very interesting little bridge because many Ukrainian nuances were connected with the image of her mother-in-law. We rarely encounter this kind of topic. But Rapay-Markish really told the story of how her mother-in-law welcomed her after her exile when she came with little Katya in her arms. Katya had been born in exile in Kazakhstan. How did her mother-in-law accept her? In her perception, what were the manifestations of Ukrainianness and Ukrainian warmth, which contained, as she put it then, a lot of what was naive and heartfelt? It was probably manifested in many everyday moments. Her mother-in-law was a simple woman who gave her a lot of insight into what relationships were and how they could warm a person’s heart.

Warming the soul and heart is such a subtle thing. Warmth was one of the reasons Rapay-Markish switched from porcelain to ceramics. To her, the former seemed factory-made, cold, and mass art, while ceramics (clay) were related to the warmth of the hands and soul. Ukraine has a great tradition in ceramics with a distinct way of thinking and using colors, shapes, color patterns, handiwork, and irregularity. Rapay-Markish was very fond of irregular shapes in which a flower, a bud, or a leaf could be expressed. This is what she contributed to the Ukrainian ceramic tradition.

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: What I see in this is childlike naivety combined with a flight of imagination and inner content.

Diana Klochko: Yes. But this naivety, like the entire stream of modernism, which emerged at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century, is still linked to a certain wisdom in attitudes to all phenomena. It’s a manifestation of archaic thinking and contains a certain wisdom of generalization, such as the images of evil creatures, of which there are quite a few in Rapay-Markish’s sculptures.

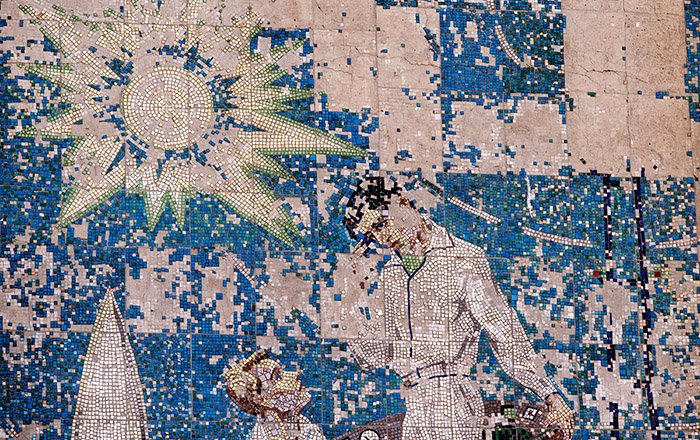

Her works in the collections of several museums, such as the National Art Museum and the National Museum of Decorative Arts, are hidden for obvious reasons. However, there is a unique children’s library where she did the decorations: a fountain with sculpted flowers, a hall of fairy tales with reliefs, and a wall dedicated to book printing. This library was unique in the former USSR and remains unique now. Unfortunately, no one in Ukraine has continued this line of monumental ceramic design.

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: Rapay-Markish’s mother, Zinaida Joffe, was a translator. She knew and worked with Vasyl Stus, which is also a significant detail for the overall picture of the environment Olga grew up in.

Diana Klochko: It was the thaw of the 1960s. At the time, Rapay-Markish communicated with Vasyl Stus directly and through her mother. She was in the center of the intellectual milieu, which included Heorhii Yakutovych and his family, Hryhorii Havrylenko, Sergej Parajanov, and others.

It was a circle of intellectuals who met daily, discussing problems and influencing each other. Their informal art seemed to stand on the edge of this highly intense discussion of all artistic problems. One issue was how Ukrainian art could become truly Ukrainian rather than Soviet. These artists lived in a situation where only Soviet Ukrainian art existed, and one of the crucial problems for them was how they could move in the direction of genuinely Ukrainian art. And we see the fruits of their labor. They discussed, deliberated, shared their insights, and were open with each other on the question of what Ukrainian art actually was and how it could be obtained.

Rapay-Markish always said (at least to me) that Jewish background was frowned upon in the USSR. Let’s not forget that. She knew how her father was executed.

Jewish art was an art in which ornament was more important than human figures. Meanwhile, she was a sculptor who wanted to depict people and animals and be part of the modernist Jewish discourse. So, her Jewish motif was modernist rather than traditional, and she said it was hidden. One of the probable reasons was that all things Jewish were not too strongly promoted in Soviet times.

Elyzaveta Tsarehradska: Putting it very mildly.

Diana Klochko: That’s why Ukrainian motifs were more important for her.

What can we say about the works of our artists of that time?

Diana Klochko: We have a museum of the Sixtiers’ movement in Kyiv with a pretty good collection of photos, letters, essays, memoirs, images, etc. And there has been growing interest in this movement and its figures.

This interest has a peculiar twist: the Sixtiers are often portrayed as victims with the predominant intonations of suffering and sacrifice. These people did go to prison, were exiled, and died. They stood in open opposition to the Soviet government. However, this is somewhat overshadowed by the stories of people who found an opportunity to develop methods of representation that bypassed all the prescriptions of Soviet ideology. We forget that many artists were not broken because they found a visual language with which they could continue the line of Ukrainian modernism. There is very little understanding of this experience.

Rapay-Markish is one such artist whose experience we can look up to. How was she able to continue working in monumental sculpture, which, in general, required some serious funding from the state? How did she navigate all the difficulties of getting approvals for her sketches and works? How did the visual artists, the dissidents of the 1960s, make it a rule to continue producing some new values through their art? They lived in Kyiv and Lviv and worked to create another language. Incidentally, Margit Sielska was also a Jew. How did the Jewish identity continue to find expression, working its way toward a different visual culture? It’s imperative to start thinking and talking about it now.

Why is Olga Rapay-Markish’s monumental art not imitated?

Diana Klochko: A negative attitude toward 20th-century exterior ceramic mosaics has emerged over a certain period. The reasoning goes that it was funded and supported by the Soviet state, artists received royalties, and thus, it “has to be destroyed.”

A number of interiors and exteriors decorated by Rapay-Markish were destroyed in the 1990s and early 2000s. We have a list of objects destroyed during this wave. At the time, it was not called decommunization. Rather, the destruction was dictated by hatred of everything Soviet.

This failure to distinguish between Soviet and Ukrainian brings a lot of grief, leading to the destruction of objects created by people who embraced a completely different public space strategy.

Our attitude toward this monumental legacy is still being guided by the shouts “Shame!”, “Destroy all sovok!” [Soviet things. — Trans.], and “They all received money!” This is a very negative trend. Unfortunately, our visual culture is at a very low level, so it’s essential to talk about such things. All these visual dissidents spoke about free means of thinking. Having destroyed their works, we are now putting up some utterly meaningless murals.

The works of people who created senses in the 20th century are now being destroyed because they are part of the Soviet legacy. And their art is being replaced by murals that have no visual appeal and carry no meaning at all. It’s garbage and an eyesore.

This program is created with the support of Ukrainian Jewish Encounter (UJE), a Canadian charitable non-profit organization.

Originally appeared in Ukrainian (Hromadske Radio podcast) here.

This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Translated from the Ukrainian by Vasyl Starko.

NOTE: UJE does not necessarily endorse opinions expressed in articles and other materials published on its website and social media pages. Such materials are posted to promote discussion related to Ukrainian-Jewish interactions and relations. The website and social media pages will be places of information that reflect varied viewpoints.