Indigenous artist Christi Belcourt’s floral artworks depict Earth’s life force and encourage regreening and sustainability.

Possibly Canada’s best-known Métis artist, Christi Belcourt paints large-scale artworks of acrylic on canvas that depict vivid floral imagery and landscapes in the natural world. Following in the tradition of Métis floral beadwork — known for motifs in which flowers typically interconnect by stems and tendrils — Belcourt’s work blooms with entwining plants, flowers, animals, and birds. Employing dots, she paints a narrative about environmental protection, biodiversity, and the spirituality of Métis culture. It’s a potent “green” narrative that has turned heads as far away as Milan, Italy, where famed fashion house Valentino featured her artwork in a collection.

“My work reflects my deep love, respect, and sense of awe for the beauty of this world and my desire for every human being to take leadership from the Earth — and to understand how we need to live in balance with each other and with the Earth,” Belcourt says.

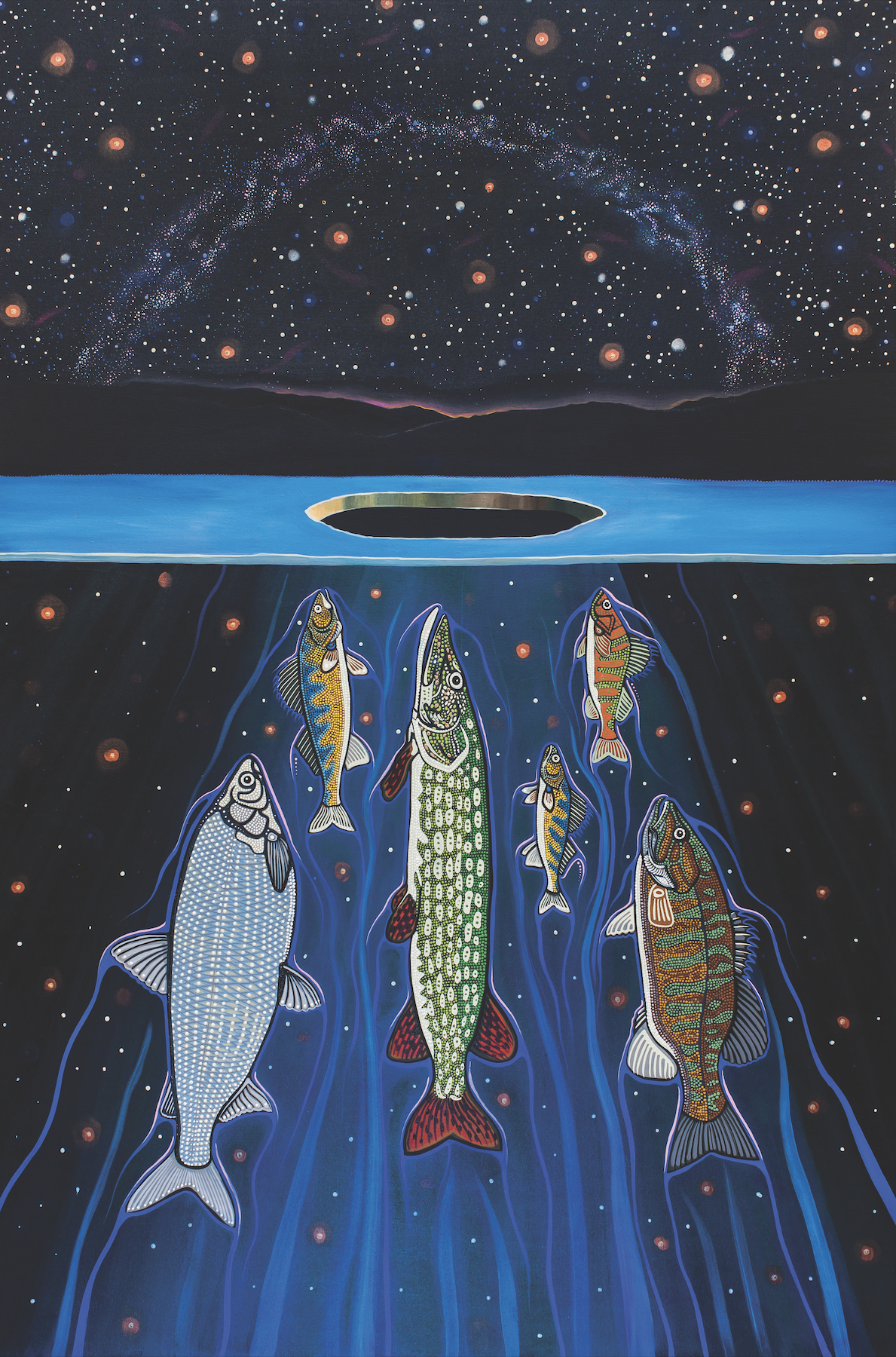

The Fish Are Fasting for Knowledge From the Spirit World, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 48 inches.

The Fish Are Fasting for Knowledge From the Spirit World, 2019. Acrylic on canvas, 36 x 48 inches.

Belcourt, 57, strives for that very balance where she lives in rural northeast Ontario province. She walks the land observing the many species around her, then depicts them in her idea-driven paintings. “There’s nothing I do that would be a landscape that would be recognized as one certain place, but I try to capture a feeling of a place,” she explains. “I have increasingly been depicting more and more species that are on the endangered species list, and that is, of course, to draw attention to those species and hopefully contribute to the awareness that needs to be raised.”

Many of her paintings include root systems, which have an artistic and figurative significance. “I believe that we are here as spiritual beings and that our lives have more meaning than what we experience on a daily basis on the surface of our life. The roots are depicted for that reason: to show the importance of soil, of plant life in giving us life. Roots absorb nutrients; then plants in turn give us food, give us medicine. Those things occur underground, and there’s this great mystery to life because it’s so big and vast and wondrous.”

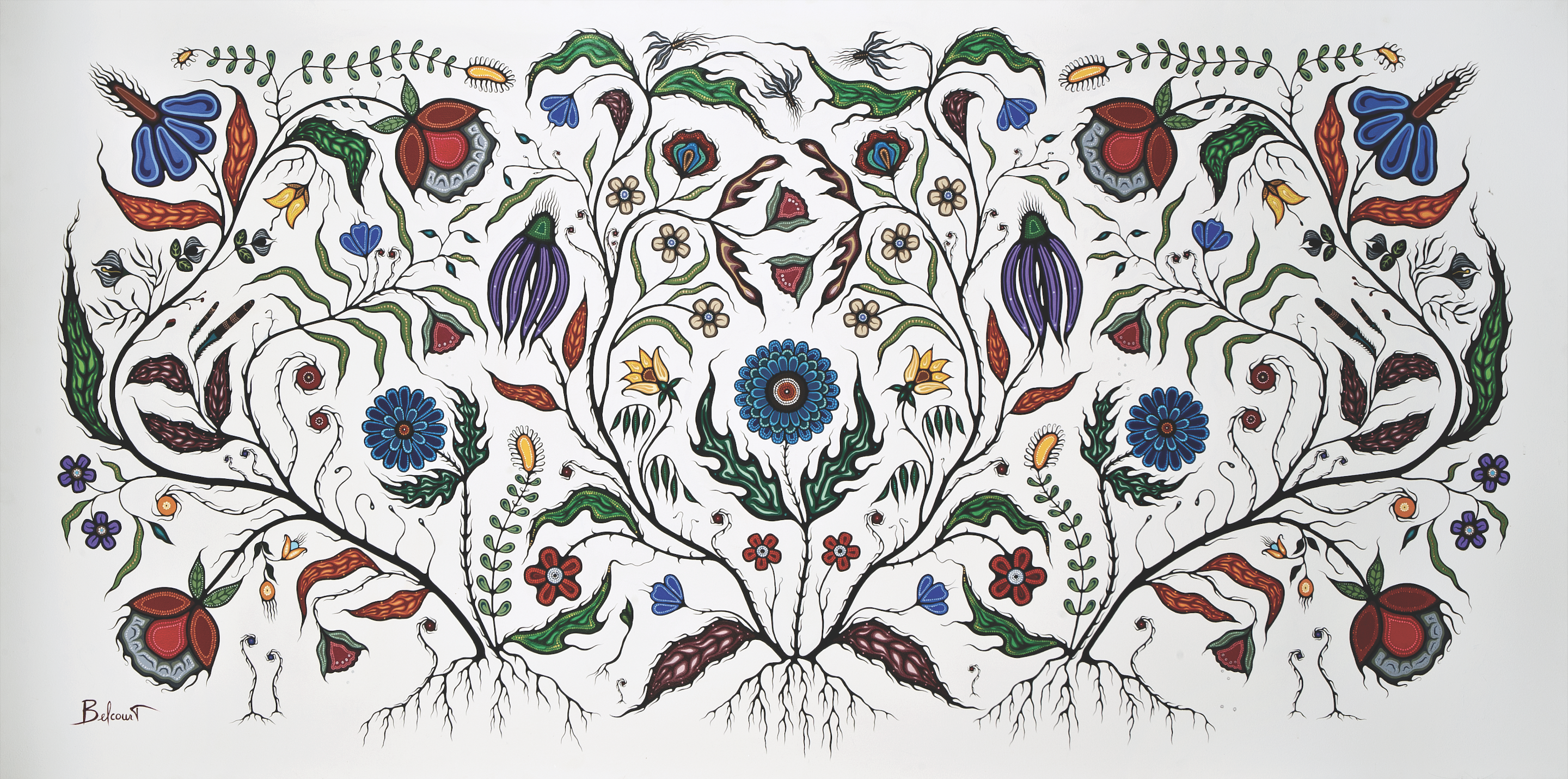

Even My Garden Knows What Peace Is, 2000. Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 72 inches.

Even My Garden Knows What Peace Is, 2000. Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 72 inches.

Belcourt, the daughter of Métis rights activist Tony Belcourt, grew up mostly in the capital city of Ottawa. She dropped out of high school after 11th grade, married, had a daughter, and in the 1990s left the city and began focusing on plant-based artworks. Her intention with her art: “To motivate people to protect the land and waters in the areas where they live.”

In Even My Garden Knows What Peace Is, she says, “The idea is, if you go on the land, and you sit on the land for a moment and quiet your mind, you understand that this Earth knows how to live in balance innately. It can bring us to a sense of health and wellbeing and balance again, if we listen to it.”

The continuing presence of Métis culture is the idea behind The Celebration, while The Fish Are Fasting for Knowledge from the Spirit World is about frozen fish that fast in winter and in doing so gain knowledge from the stars, knowledge humans can absorb when later eating the fish. North Star recognizes the stars that have always guided the totality of life, with an underlying message cautioning against satellite pollution filling our skies. Likewise, The Night Shift is an ode to the moths and other insects that do the work of pollination at night.

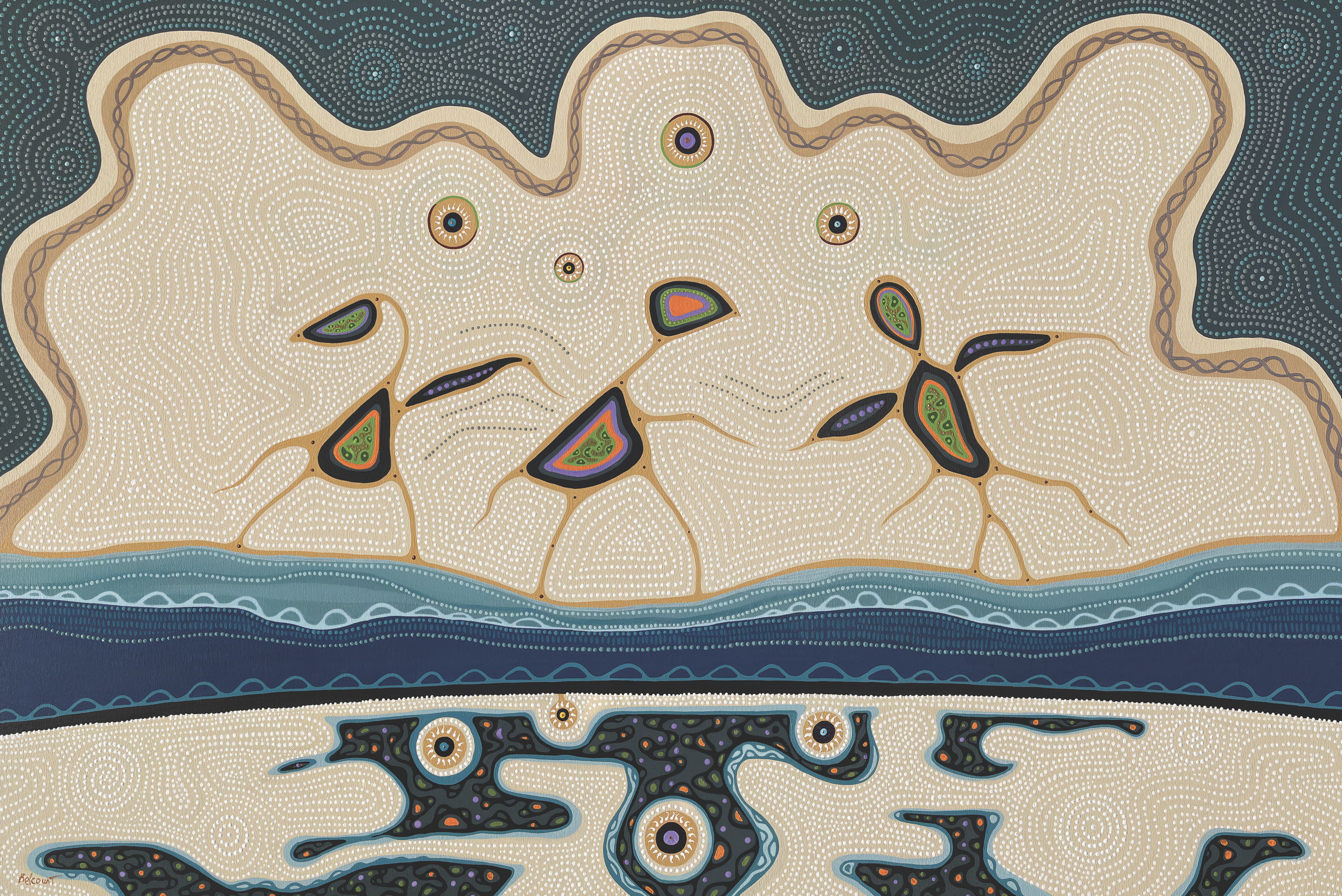

Tree Spirits Leaving Before the Fire, 2007. Acrylic on canvas, 24 x 36 inches.

Tree Spirits Leaving Before the Fire, 2007. Acrylic on canvas, 24 x 36 inches.

Belcourt’s community activism extends beyond her paintings. She was the project creator of Walking With Our Sisters, a commemorative art installation of more than 1,700 moccasin vamps created to recognize the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls movement that seeks to bring awareness to the pervasive problem. As co-creator of #Resistance150, she reminded Canadians that Indigenous people have occupied the land for 15,000 years and have historically resisted discriminatory practices. She co-created the Onaman Collective for Indigenous language and arts preservation and has used her art to print thousands of banners to spur community action on water and land protection.

“Communities are left entirely powerless when corporations want the resources that they have their communities on,” Belcourt says. “They have no recourse with which to stop ‘development.’” The way Belcourt sees it, it’s incumbent on all of us as people, and on her as an artist, to fight for the next generation.

Belcourt’s art is part of Radical Stitch, a group exhibit touring in 2024, including a stop at the National Gallery of Canada. She has two pieces in the exhibit How to Survive, mounted at the Anchorage Museum in Anchorage, Alaska, through January 19, 2025. She also has a commission from the Philbrook Museum in Oklahoma in 2024.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the artist

HEADER IMAGE: The Night Shift, 2023. Acrylic on canvas, 76 x 102 inches.

From our October 2024 issue.