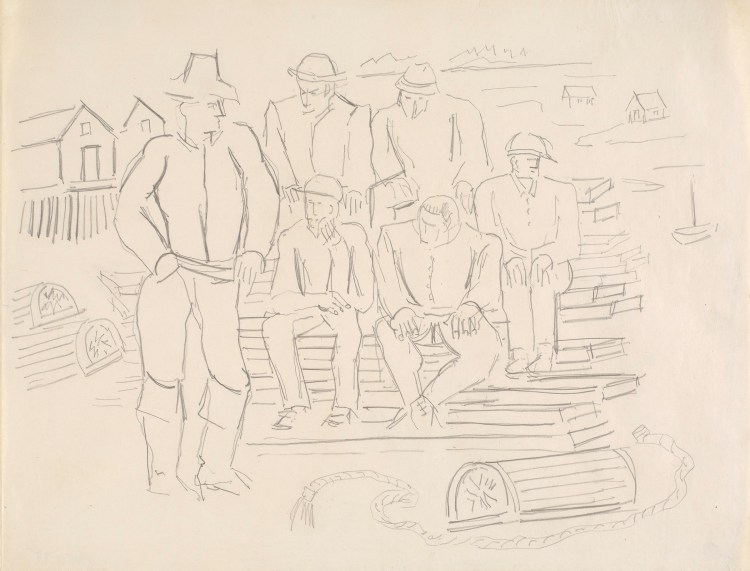

Marsden Hartley, (Preliminary drawing for Lobster Fishermen), ca. 1940, graphite on paper, 8 1/2 x 11 inches, Bates College Museum of Art, Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection, Gift of Norma Berger, 1955.1.79

This summer, Maine’s art institutions offer up exhibits showcasing a multitude of genres and media, historical evaluations of 19th- and early 20th-century artists, and more contemporary perspectives from women, Wabanaki culture and Black life. Here are seven shows not to miss.

“Hartley | Hopper: Drawings from Two New England Collections”

June 7 to Oct. 6, Bates College Museum of Art, Lewiston, 207-786-6255, bates.edu/museum

Edward Hopper, “Study for Cape Cod Morning (no. 1 of 4),” n.d., graphite on paper, 7 x 8 5/8 inches, Provincetown Art Association and Museum, Gift of Laurence C. and J. Anton Schiffenhaus in memory of Mary Schiffenhaus, and two anonymous donors, 2016

This show represents a collaboration between Bates’ Hartley Memorial Collection and The Provincetown Art Association and Museum’s (PAAM) Hopper collection, both of which steward major holdings of these artists’ works, studio materials, photos, diaries, correspondence and ephemera. It’s an intriguing pairing of two artists with much in common. Marsden Hartley and Edward Hopper both painted in the 1930s and ’40s and were preoccupied with the human figure as well as landscape, and both worked in maritime locales rich in natural beauty. The exhibition, which will travel to the PAAM after its Bates run, will create interesting juxtapositions between Hartley’s beefy male nudes – i.e., “Flaming American (Swim Champ)” of 1939-40 – and Hopper’s nude women, such as “Seated Woman with Cat” of 1942-43. We will also be able to compare Hartley’s “Sailboats at Anchor in a Cove” (1930) with two untitled studies of a sailboat by Hopper. A bonus will be preliminary graphite-on-paper studies for well-known masterworks such as Hartley’s “Lobster Fishermen” (now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art) from 1940-41 and Hopper’s “Cape Cod Morning” of 1950 (now in the Smithsonian).

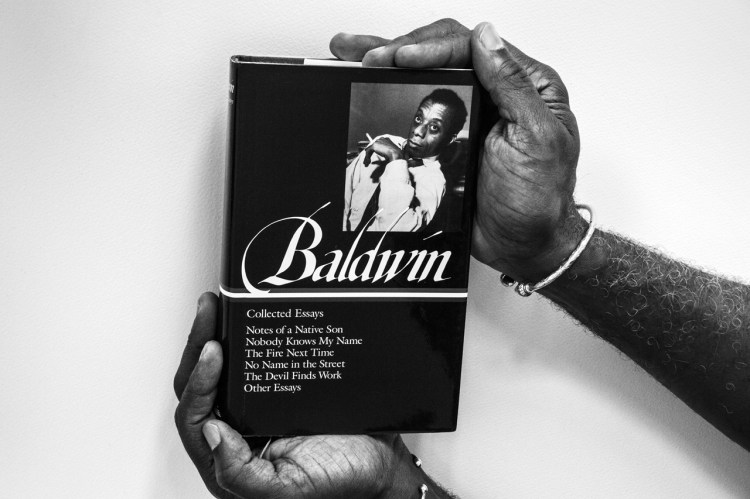

Arnold Joseph Kemp, “Possible Bibliography (detail),” 52 black and white archival inkjet prints; unique closed edition, 2015 – 2020, The Fine Arts Collection, Jan Shrem and Maria Manetti Shrem Museum of Art, University of California, Davis. Museum Purchase.

“To Whom Keeps a Record | Arnold J. Kemp”

May 25 to Sept. 8, Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Rockland, 207-701-5005, cmcanow.org

About the color black in his work, artist Arnold J. Kemp has said: “For me it is a color, a reference to race, since I am a Black person, and also as a reference to a kind of magic. Black can also represent a sort of spiritual seeking.” This contemplative show, curated by Portland-based artist Ashley Page, embodies a deeply personal, conceptual exploration of Blackness in its many racial, cultural and spiritual dimensions. “Possible Bibliography,” for instance – a work of 52 black-and-white inkjet prints in which Kemp photographs his hands holding up literary works from his own library by James Baldwin, Toni Morrison, Wanda Coleman, Cornel West, Glen Ligon and other Black literary and artistic giants – speaks to his abiding interest in cultural criticism and perception of Black artists and thinkers. In his sculpture “Music Brings Goodness to Us All Unless One Has Some Other Motive for Its Use,” we can interact with vinyl records from his personal collection that feature music by jazz pioneers, but also archival recordings from Black scholars, political figures, historians and other thought leaders. It’s an immersion in, according to the CMCA description, a personal archive that “serves as a reminder of today’s socio-political landscape and its reverberations in the Black psyche.”

Eastman Johnson, “Shelling Corn,” 1864, oil on academy board, 15 3/8 x 12 1/2 in. (39.1 x 31.8 cm), Toledo Museum of Art; gift of Florence Scott Libbey, 1924.35 Richard P. Goodbody Inc./courtesy of Colby College

“Eastman Johnson and Maine”

June 6 to Dec. 8, Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, 207-859-5600, museum.colby.edu

Colby dives into the legacy of this 19th-century painter born in Lovell and raised in Fryeburg and Augusta. Eastman Johnson is not an artist we hear much about these days, despite having been co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the author of famous portraits of Abraham Lincoln, fellow native son Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and other figures. The exhibition concentrates on Johnson’s genre painting and, compared with the other shows featured here, is a throwback to another time, long before our contemporary consciousness made artists like Johnson unfashionable. In its focus on domestic scenes of people making maple sugar, shucking corn, children sitting in a hayloft and so on, we can glean the influence of 17th-century Flemish and Dutch Masters, likely due to Johnson’s time in the Hague, which he followed with studies in Paris (Jean-François Millet is another obvious influence). Johnson is to New England genre painting what George Caleb Bingham was to the depiction of life and commerce on the Missouri River. He is enigmatic to some extent. The painting that arguably cemented his artistic reputation, “Negro Life at the South,” has been interpreted as both criticizing and romanticizing slavery. While Johnson’s sister married an abolitionist preacher, his father’s second marriage was to a Southern woman who owned three slaves. The Colby show is unlikely to take up this debate. But whatever Johnson’s true sentiments, it is easy to take pleasure in his distinctive style and the agrarian idylls he was fond of painting.

Lynne Drexler (1928-1999), “Flowered Convention,” 1965, oil on linen, 68 1⁄2 x 88 inches, Gift from the estate of the artist, 2002.15.2, © 2024 Lynne Drexler by permission of The Lynne Drexler Archive

“Lynne Drexler: Color Notes”

Through Jan. 12, Farnsworth Art Museum, Rockland, 207-596-6457, farnsworthmuseum.org

By now, Lynne Drexler is a household name thanks to a long overdue re-appraisal of her oeuvre, which was overshadowed in her lifetime by an art scene mostly interested in white male Abstract Expressionists. This is that rare exhibition that brings together seven paintings and a dozen works on paper from private collectors and three museums – The Farnsworth, Bates and the Monhegan Museum of Art & History – to tell a well-rounded story of the artist’s most critically acclaimed period: the 1960s. As the title indicates, it highlights her iconoclastic talents as a colorist. But evident also are the rhythmic musicality of her canvases, as well as her connection to familiar landscapes from her native Virginia (“Cismont”) to her beloved Monhegan Island (“Shimmering Rays” and “Flowered Convention”), where she lived until her death in 1999. Three paintings, in particular, measure over 85 by 65 inches. Drexler’s work at this scale is spectacular and not often exhibited, so they are guaranteed to stop you dead in your tracks.

Elena Jahn, 1938-2014, “Red Rocks, Monhegan,” 1959, oil on canvas, 24 x 28 in., collection of Lisa Jahn-Clough Courtesy of Monhegan Museum

“Women Artists of Monhegan Island: A Common Bond”

July 1 to Sept. 30, Monhegan Museum of Art & History, Monhegan Island, 207-596-7003, monheganmuseum.org

Until the re-discovery of Lynne Drexler, exhibitions largely ignored the significant contributions of women artists to the creative life of one of Maine’s most prominent summer art colonies: Monhegan Island. In 2007, the University of New England featured the work of 36 female artists who worked on this dramatic speck of land 10 miles off the coast of Maine. Women Artists of Monhegan Island (WAMI) – a group established in 1990 by Elena Jahn and Frances Kornbluth and still extant today – created community among female painters of the colony by generating artistic exchanges, fostering their work and also creating exhibition possibilities for their art. The show promises a variety of styles and genres. Among the highlights: “Red Tide Pool” by Sylvia Alberts (which straddles representation, abstraction and pattern art); the more vigorously abstract works of Jahn (“Red Rocks, Monhegan”) and Nancy Thompson Brown (“Pond Life”); graphically informed pieces such as an untitled Frankie Odom ink print embossment on paper and Arline Simon’s mixed-media “Pictures at an Exhibition”; and a fascinating Joan Rappaport watercolor that simultaneously suggests a tree and the inner spirit that might reside there. It’s well worth an early morning ferry ride to hike around the island and immerse yourself in the landscape that informed their art. You can also find work of current WAMI members such as Kate Cheney Chappell and Joan Harlow at the island’s Lupine Gallery.

Lee Krasner, “Lavender,” 1942, oil on canvas, 24 x 30 inches. Guillermo Gonzalez. Image courtesy of Kasmin, New York. Photo by Angus Hill. © Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

“Lee Krasner: Geometries of Expression”

Aug. 1 to Nov. 17, Ogunquit Museum of American Art, Ogunquit, 207-646-4909, ogunquitmuseum.org

In 1972, Lee Krasner demonstrated with some 300 female artists (including Louise Bourgeois and luminist sculptor Chryssa) and art historians (Cindy Nemser) in front of the Museum of Modern Art, accusing the institution of discriminating against women artists (one sign read: “MOMA Prefers Papa”). This show presents the artist’s geometric abstraction as part and parcel with her progressive thinking and her relationships with colleagues in the American Abstract Artists Group such as Willem de Kooning, Arshile Gorky, Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still. Krasner’s career, of course, was often eclipsed by that of her hard-drinking, womanizing husband, Jackson Pollock, so she knew firsthand what it felt like to have one’s work disregarded simply because of her gender. It was Krasner, however, who introduced Pollock to people like de Kooning and critic Clement Greenberg (who later lauded Pollock’s work while decrying Krasner’s), and Krasner who debated issues of art vociferously at the Artists Union (leaving when she realized the club was being infiltrated by Communists). This show zeroes in on her formative years in the 1930s and early ’40s, before she met Pollock, and during which she worked for the Works Progress Administration’s Federal Art Project (which later became the War Services, for which she created collages in various department store windows to support the war effort).

“Basket in progress in Frey’s studio,” 2023. Photo by Jared Lank (Mi’kmaq)

“Jeremy Frey: Woven”

May 24 to Sept. 15, Portland Museum of Art, Portland, 207-775-6148, portlandmuseum.org

In March, a New York Times profile of the seventh-generation Passamaquoddy basket maker Jeremy Frey stated, “Frey’s vibrant and innovative baskets – remarkably contemporary forms woven with ancestral knowledge – have caught the attention of the art world and put him at the forefront of a wave of interest from museums, galleries and collectors in the work of Native artists.” Now, he has the first-ever solo exhibition of a Wabanaki artist in a museum. The elevation of this Bangor-area artist’s work in the eyes of the art cognoscenti is significantly due to the efforts of Jaime DeSimone, who early on championed his basketry as a unique hybrid of sculpture and exquisite ancient craft while at the Portland Museum of Art (she is now chief curator at the Farnsworth Art Museum and has organized this exhibition with Ramy Mize, associate curator of American art at the PMA). Frey’s baskets are masterful, employing ash he harvests from the woods, along with sweetgrass, birch and cedar bark, spruce root, dyes and porcupine quill work employed in images of wildlife that carry cultural resonance among the Wabanaki peoples. Adding urgency to the exhibition, and underscoring Frey’s connection to the nature around him and the centuries-old tradition he is innovating, is the emergence of the invasive emerald ash borer that has decimated the black ash trees that comprise a major element of his art. (The Farnsworth will also present “Magwintegwak: A Legacy of Penobscot Basketry” from May 25 to Jan. 5, which chronicles the tent market in Lincolnville Beach run by the Shay and Anderson families since the 1930s to promote Penobscot basketry.)

Jorge S. Arango has written about art, design and architecture for over 35 years. He lives in Portland. He can be reached at: jorge@jsarango.com

Related Stories

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you’ve submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.