Born Judy Cohen in Chicago in 1939, pioneering feminist artist Judy Chicago has, over the span of a 6-decade career, sought to address “absence and erasure” with her oeuvre. Chicago was brought up in a liberal Jewish household which emphasized the importance and joy of art, culture and social justice, ingraining in her a steadfast passion for all three. In the 1970s, Chicago became inspired by and actively involved in the women’s liberation movement, and, “in an effort to liberate herself from the confines of patriarchal traditions,” dropped her married name and took the surname “Chicago” in honor of her own birthplace. Encapsulated within her name is the artist as we have come to know her: working for the collective, whilst remaining fundamentally and crucially herself.

In the Serpentine North Gallery’s exhibition “Revelations,” Chicago’s unpublished, early 70s manuscript by the same name takes center stage. Focusing on the centrality of drawing to Chicago’s creative output, this exhibition is organized around the five chapters of the manuscript and follows Chicago’s career and artistic development as she found her voice, and chose to use it to amplify women’s and feminist art. The space is immediately striking, with the sprawling, 30-foot-long, psychedelic masterpiece “In the Beginning” from her revolutionary “Birth Project” opening out in front of you as you enter. Colorfully delineated sections guide you through the chapters and, in tandem, the evolution of Chicago’s practice.

Beginning in a section titled “Revelations of the Goddess,” we are introduced to Chicago’s early works from the late 60s to the early 70s. Chicago found the Los Angeles art scene “inhospitable to women” and thus avoided creating explicitly “female” works, focusing instead on minimalist, geometric and abstract pieces. These works are undeniably visually appealing, but also visually low-risk; they speak clearly to the way in which Chicago’s voice was suppressed by the male-dominated, sexist culture within which she was creating, leading her to focus on accepted, palatable media. This provides a brilliant foil to her later works: Her abstracts are nice, but as she develops, she seems to discard a concern with the nice altogether in preference of the personal, the affronting, the unapologetic. In some ways, whilst of course it makes sense chronologically and thematically to start here, it does feel like an undersell of the exhibition on the whole. However, although we do not begin with the most exciting or attention-grabbing works, to see the process through which Chicago transformed from this point to where she finds herself now is truly moving.

The curation by Hans Ulrich Obrist (artistic director), Chris Bailey (associate exhibitions curator) and Liz Stumpf (assistant exhibitions curator) demonstrates a real dedication to elucidating this process. Next comes a collection of works that are still, for all intents and purposes, abstract, but evidence a distinct move into a more symbolic, politicized abstraction. Here, with works like “Through the Flower” and “The Extended Vagina as the Goddess Diana,” Chicago’s artistic and social consciousness shines through. In her iconic piece “Peeling Back,” Chicago places an abstract, geometric lithograph above her own handwriting, explaining the experience of having felt “rejected and diminished” by specific men in the art world, and the resultant idea of rejecting pure abstraction in favor of embracing meaning. “Here I am, with a woman’s body and a woman’s point of view,” announces Chicago, as she combines established practices with her individual agency and transitions into a more politically engaged creative period.

Across the following sections — “Myths, Legends and Silhouettes” and “The Yearning” — we come to understand why Chicago is considered such a polymath, and such a cross-disciplinary, multimedia talent. Her monumental installation “The Dinner Party” (1974-79), on permanent view at the Brooklyn Museum since 2007, arose from “a desire to excavate women’s achievements and counteract their erasure from dominant narratives.” Designed on a colossal equilateral triangle of a banquet table, “The Dinner Party” is a dedication to the overlooked and unknown history of women’s achievements, featuring 39 place settings for specific women, and 999 further names inscribed around them. Describing the process via a video clip shown in the room, Chicago explains that “this was the first time in my life that being a woman artist was a distinct advantage,” as she was able to partake in the learning of female-dominated ceramic art and thus reclaim a medium so often denigrated due to its feminine associations in a misogynistic culture. In “The Yearning,” we are given insight into Chicago’s 1968-74 foray into pyrotechnics, a medium that she employed to create “Atmospheres,” her set of immersive performances made up of smoke sculptures. Branching across fields, Chicago demonstrates not only a mastery of a broad range of artistic techniques, but also an ability to translate her belief system through any medium.

“The Calling of the Apostles and Disciples” is a fascinating chapter of the exhibition. Chicago’s series “PowerPlay” (1982-87) “signifies a pivotal shift” where she put forward the idea that “male artists have represented women’s bodies for centuries; if they could do it with women, why can’t I do it with men?” In pieces like “Pissing on Nature” and “Weeping Maleheads: If Only They Could/Would,” Chicago interrogates the concept of masculinity, using the series to express her myriad emotions built up over “years of dealing with men” and create grotesque portraits to express the idea that men are “disfigured by power.” Within these works, Chicago considered gender relations and theory, describing how when one looked for texts on the subject of gender, they only found texts on women, because “consciousness had not yet evolved into the realization that men have a gender too.” Shown in a glass case is Chicago’s handwritten list beginning “If I were a man: I’d hate:” which moves from the profound — “going to war,” “not being able to cry” — to the banal — “having to wear ties,” “getting bald” — to the phallic — “having a penis that hangs between my legs,” “worrying about whether my penis was big enough.” Her approach to gender as an area of study and consideration is evident: She criticizes the existing power structures, and takes an active interest in the victimhood of men at the hands of their own systems.

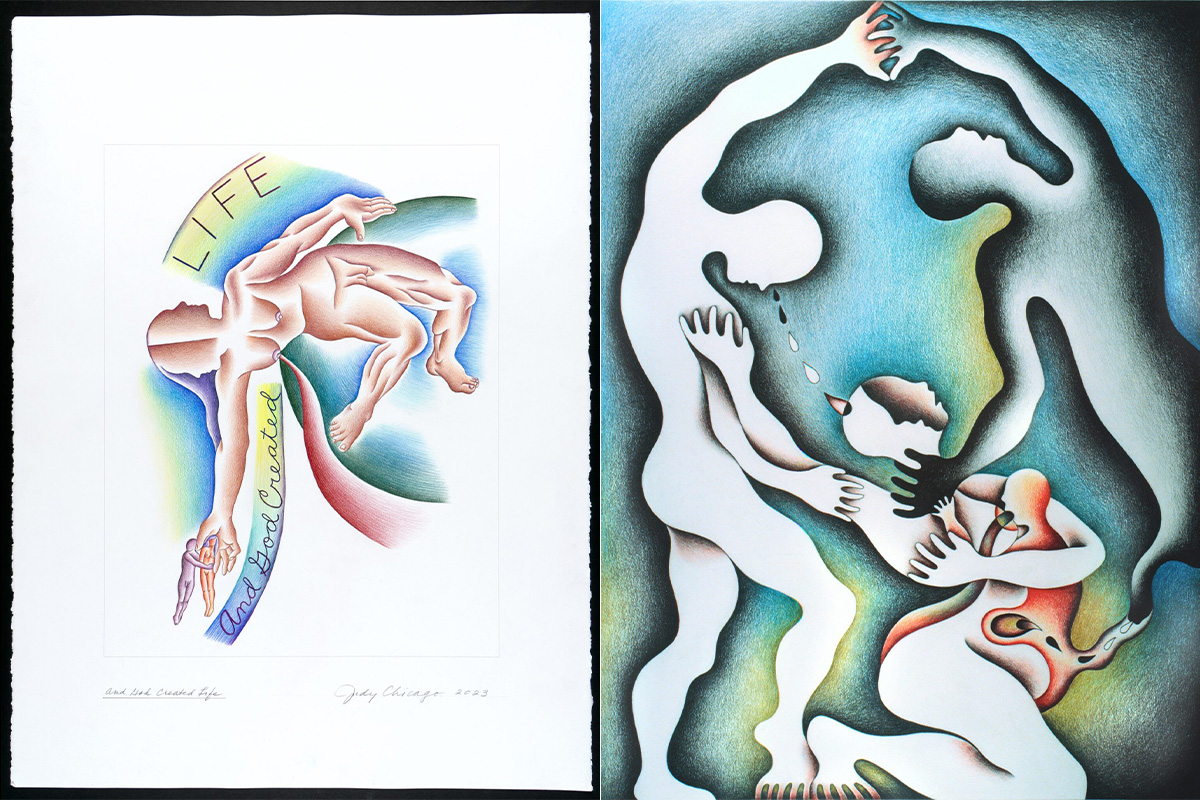

Chicago’s final section, “Visions of the Apocalypse,” is my personal favorite. In Judy’s address at the Serpentine — the 84-year-old artist was present for the opening — she referenced a visit to the Sistine Chapel and the idea that it stirred in her: “A male god reaches out his finger and created man? I don’t think so! That’s not how birth happens!” In creating her “Birth Project” (1980-85), Chicago draws on her longstanding interest in mythology to present images of labor, motherhood and creation which cover “the mythical, the celebratory, the painful.” A return to drawing is deeply impactful here — the simplicity of the pieces speak to the fundamentality of the subject matter and emphasizes its visceral, beautiful nature. “If men had babies, there would be thousands of images of the crowning,” argues Chicago in the gallery’s abstracts. Across this section, and the glorious, large-scale “In the Beginning,” Chicago celebrates the process of labor, depicting it not only as a human experience but also a universal one; in the opening words of her manuscript, Chicago narrates that “then one last wail sounded in the Universe as Woman was born onto the Earth.”

The Serpentine exhibition is a loyal tribute to the legacy of Judy Chicago’s work as a feminist, activist and artist. Tracing Chicago’s career from her 1960s abstractionism all the way to her 2022 collaboration with Pussy Riot’s Nadya Tolokonnikova in the global call-and-response project “What If Women Ruled the World?”, the curation is thoughtful and precise, doing justice to the magnitude and fortitude of Chicago’s output. It is a total joy to behold, as Chicago artistically births her own identity and her own voice, over and over again.

“Judy Chicago: Revelations” will run at the Serpentine North Gallery from May 23, 2024 through Sept. 1, 2024.