Untitiled works at the exhibition

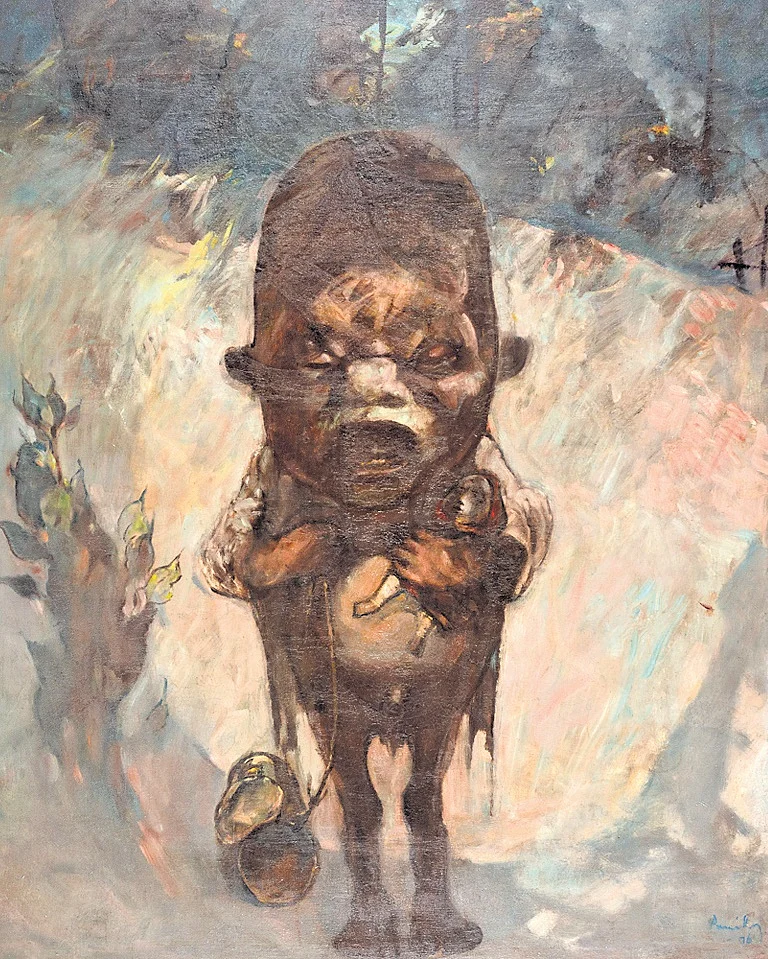

The painting by KCS Paniker that awes you at the Madras Modern: Regionalism and Identity exhibition by DAG, almost looks like a dystopian version of Humpty Dumpty. The dark colours and menacing face with an open cavernous mouth will haunt you. It stays with you for a long time after walking out of the gallery.

But what surprises at the same time, is that of the over 50 works on display, there are probably just a few names that one would connect with. Showcasing the works of a core group of artists of the Madras Art Movement, the exhibition tries to address the lack of information and awareness regarding the works of artists from the Madras School of Art. The first iteration opened in 2019 in Mumbai.

Why did the Madras School remain almost a sideshow? “One primary reason is that though the Madras School of Art (now the Government College of Fine Arts) was established in 1850, its visual art department had a very late beginning. It began only in 1930 under the tenure of DP Roy Chowdhury, its first Indian artist principal.

The other art centres were well established by then with a robust infrastructure of artists, patrons, collectors and gallery system. There was a thriving art community in places like Calcutta and Bombay,” says Kishore Singh, Senior VP, DAG. But just setting up a department was not enough.

Though the artists were hugely proficient, they were not included in exhibitions in the other centres because there was lack of knowledge about them. Madras didn’t have a robust art community. And being a late starter, getting patronage in the art centres of Calcutta and Bombay—which boasted the Bengal School of Art and the Progressive Movement respectively—was difficult.

To counter this, Paniker founded the Cholamandal Artists’ Village in 1966. Located in Injambakkam, it is the largest artists’ commune in India. This community provided a thrust to the art school. “The Madras Art Movement revolved around the pedagogy of the Madras Art School. To take it forward—post students passing out from there—Paniker’s idea was to create a community where people could sit together and exchange ideas around art making and practices.

It was that that became the catalyst for setting up the Cholamandal Artists’ Village. The community—artists residing together, communicating with each other, working together—provided a big boost of momentum to the movement. It brought into focus the artists as a cohesive unit practicing a certain kind of modernism that made them distinctive,” says Singh.

One distinct theme of the movement—evident in the ongoing exhibition—is the use of mediums differently. The modernists work typically with canvas, oil, acrylic, water colour, paper, gouache. That aspect of using materials was the same in Madras, but the treatment was different. The sculptors within the group, instead of working typically in the round, worked on frontal sheet-based image with repousse work (hammering a malleable metal from the reverse side) being a significant character in their practice.

Another theme that strikes viewers is that of regionalisation of the art works. Singh says, “The whole idea of Madras Art Movement was based on localisation with a Southern influence, which includes their mythology, their architecture, their design. All these found a significant place within the purview of their practice.”

While the Cholamandal community helped the Madras Art Movement thrive, it lost its space to emerging contemporary art in the 70s and onwards, which began to take over the market and change the dynamics. With this exhibition, the gallery hopes to shine much-needed light on the hidden canvas.