Trigger warning: Art can cause reactions. It can make you think about yourself and the world around you, especially when the artwork is visually or conceptually provocative — or both — as it is with former North Idaho-based artist Edward Kienholz.

In 1966, local officials threatened to shut down Kienholz”s solo show at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art for his gritty, three-dimensional depictions of taboo topics like sexuality and abortion.

“Kienholz was always just staring directly into the face of American sexual and moral and racial hypocrisy and throwing it into people’s faces in the art context — in the museum — and then calling attention to the fact that, you know, we go to museums to look,” says Johanna Gosse.

Gosse is the guest curator for “Beyond Hope: Kienholz and the Inland Northwest,” on display at Washington State University’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum through June 29.

“At the same time that he’s calling out our cultural hypocrisy, he’s also pointing out our voyeurism,” she adds.

With her extensive background studying postwar art and visual culture, especially West Coast assemblage art, Gosse had heard of Kienholz, of course, but thought of him in the context of his Los Angeles background.

Then around six years ago, she had a serendipitous encounter with Kienholz’s installation at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City titled “The Non-War Memorial,” which the artist proposed should be staged in northern Idaho.

“I think I looked at that and I said, ‘Oh my goodness, Clark Fork, Idaho,'” recalls Gosse, who knew she would be moving to Moscow, Idaho, in the fall of that same year to join the University of Idaho as an assistant professor of art history and visual culture.

Once she began developing curriculum for her university students, Gosse delved into Kienholz’s ties to the Inland Northwest, including Bonner County, where he and his wife and fellow artist, Nancy Reddin Kienholz, moved in 1972. (As such, all collaborative works by the couple from 1972 onward are simply referred to as by “Kienholz,” although some works in the WSU showcase are solely by Edward.)

Other local connections include the University of Idaho, which hosted the artist in 1979, and the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture, which owns Kienholz’s Spokane-based tableau, “The Jesus Corner.”

No trigger warnings have been posted for the WSU show, which unlike some of Kienholz’s earlier exhibitions, focus less on the artist’s social and political content than it does sense of place, specifically Eastern Washington and North Idaho.

“Beyond Hope” includes three plaques from 1964 to 1966 detailing Edward Kienholz’s plans for a conceptually rooted tableaux, or life-size narrative diorama. He designed one, “After the Ball Is Over,” to take place in Fairfield, Washington, where he was born.

Kienholz envisioned another piece, “The World,” taking place on a specific five-acre plot in Hope, Idaho, where he lived and worked with Nancy until his death in 1994 (Nancy died in 2019).

“I plan to sign the world as the most awesome ‘found object’ I have ever come across,” Kienholz wrote in a proposal for “The World,” which was never realized. “I chose this place because of the natural beauty that is there and because the world really does need hope.”

It was important to include these “Concept Tableaux,” says Gosse, noting that they are “considered some of the first really inaugural works of conceptual art in the United States.”

The works also point to Kienholz’s valuation of the rural areas of his youth as “full of potential rather than these inert, marginal places,” she adds.

Indeed, Kienholz’s 1970 plans for “The Non-War Memorial,” a small visual representation of which is included in the WSU show, cited a 75-acre plot near Clark Fork, Idaho, as the ideal location for the

time-lapse installation. He proposed filling 50,000 U.S. military uniforms with a thick, gooey clay and leaving them to decompose — like the more than 48,000 soldiers killed in Vietnam at the time of his proposed artwork.

“Beyond Hope” is actually several exhibitions spread over several spaces. In addition to the mixed-media assemblages and other artwork in the main gallery, the show highlights the couple’s studio practice, which was split between Hope and West Berlin, and the dynamic, arts-based community the couple created in and around their compound, as they called it.

There is footage of the Kienholzes hunting, for example, plus ephemera representing their friendships with regional artists, including the late Robert “Bob” Helm and his wife, Tamara Helm, both WSU art professors.

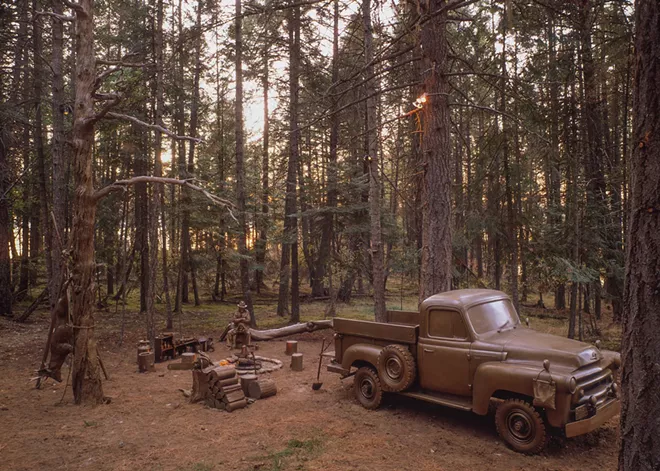

A life-size photograph of a 1991 installation Kienholz called “Mine Camp,” plus some bronze objects from the tableau, points to another aspect of how sense of place played into the couple’s many modes of artmaking.

On one level, it seems like a familiar and innocuous representation of a hunting camp — an old truck, a deer carcass hanging from a tree, a grizzled hunter, camping gear — except that the pieces are cast in bronze. In addition, “Mine Camp” was part of the Kienholzes’ attempt to have their entire compound designated as an art installation, echoes of earlier conceptual works like “The World,” in which everything was or could be understood in terms of it being art.

The Hope compound was also a hotspot for art events. The Kienholzes’ Faith and Charity in Hope Gallery was a big draw, showing such big-name artists as Francis Bacon and Alberto Giacometti, with gallery events typically followed with a big dinner or other social gathering.

Gosse says one of the reasons the Kienholzes started the gallery was because Ed’s son attended a career day at school and many boys said that they wanted to be truck drivers when they grew up.

The idea was to bring “a more global, creative world to Hope,” she says.

But, she continues, “the ways that [Kienholz] used this place that is known for being intensely remote and private to have a kind of public facing life is such a curious contradiction that speaks to the ways that they always just kind of ran against the grain.” ♦

Beyond Hope: Kienholz and the Inland Northwest • Through June 29; open Tue-Sat from 10 am-4 pm • Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art • 1535 N.E. Wilson Rd., Pullman • museum.wsu.edu • 509-335-1910