If you have been keeping a weather eye on the discovery, rehabilitation and reordering of female artists that has been in full swing for the past half-dozen years or so, 2026 offers a rich selection of distaff painters and makers – both ancient and modern. Tate Modern, for example, presents the two biggest names: “Frida: The Making of an Icon” (25 June 2026 – 3 January 2027), a British genuflection to the cult of Kahlo, and “Tracey Emin: A Second Life” (27 February – 31 August), a display of her sploshy solipsism. Both will provide an opportunity to judge whether their art actually measures up to their column inches.

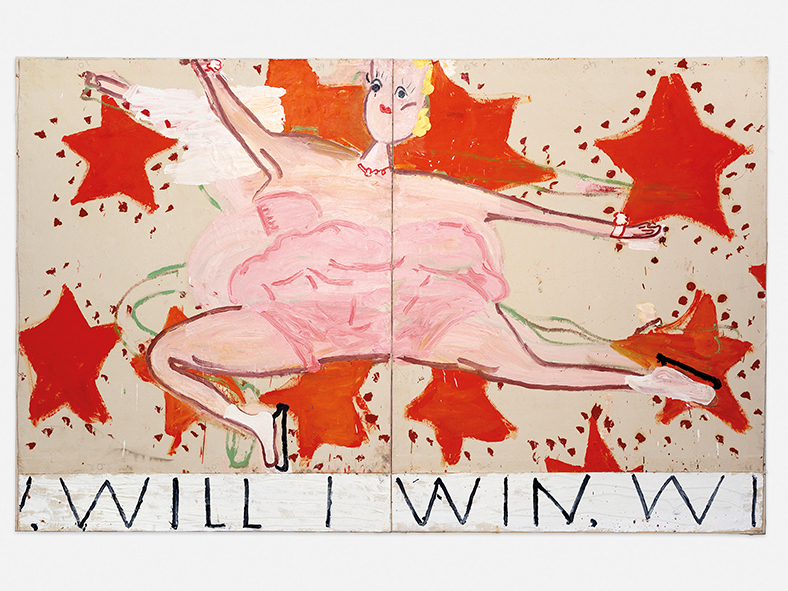

More intriguing pleasures are promised by “A View of One’s Own: Landscapes by British Women Artists, 1760-1860” (Courtauld Gallery, 28 January – 20 May), a peek at a genre in which women traditionally have barely figured, and “Chiharu Shiota: Threads of Life” (Hayward Gallery, 17 February – 3 May), featuring the Japanese artist who uses skeins of red wool to transform objects (boats, chairs, even shoes) and spaces into dreamlike webs. Meanwhile, the vigour of Rose Wylie (Royal Academy, 28 February – 19 April) seems not to dim with the passing years, while Cecily Brown (Serpentine South, 27 March – 6 September), purveyor of sensual, colour-loaded expressionism, is a painter in her pomp.

Two trailblazers are also due a welcome outing: “Catharina van Hemessen” (National Gallery, 4 March 2026 – 30 May 2027) will present the 16th-century Flemish portraitist who was considered important enough in her lifetime to merit a mention in Vasari’s Lives of the Artists, and “Michaelina Wautier” (Royal Academy, 27 March – 21 June 2026) reveals an extraordinarily accomplished 17th-century Fleming who sought expression in the faces of her subjects – a curled lip here, a sideways glance there. Their distant heirs include the mystical abstract painter Hilma af Klint (“Artist and Visionary” at the National Gallery of Ireland, 15 October 2026 – 7 February 2027), the still underrated St Ives modernist Wilhelmina Barns-Graham (Tate St Ives, 24 October 2026 – 11 April 2027), and the inventive and humorous designer-artist Enid Marx (Compton Verney, 18 July 2026 – 3 January 2027).

There are some pretty decent male artists on show too. The two stand-outs are both at the National Gallery. Francisco de Zurbarán, a painter of great potency whose religious paintings use tenebrism to dramatic – and meditative – effect, is sometimes half-dismissed as the “Spanish Caravaggio”, but he now steps out from the latter’s shadow (2 May – 23 August). And what a coup for the same institution to stage “Van Eyck: The Portraits” (21 November 2026 – 11 April 2027), a display of all the vanishingly rare portraits by one of art’s founding fathers. Jan van Eyck was one of the first artists to show the possibilities of the genre, released through oil paint, and his Arnolfini Portrait (1434) shows just two of a series of startlingly immediate faces.

It might seem odd to place George Stubbs as a descendant of Van Eyck but he was every bit as attentive to the nuances of horse flesh as the Flemish painter was to facial flesh. Stubbs’s Whistlejacket (1762) has long been one of the favourite paintings in the National Gallery and with “Stubbs: Portrait of a Horse” (12 March – 31 May) he will share a paddock with “Scrub”, another monumental, riderless rearing horse. The picture, painted for the Marquess of Rockingham around 1762, remains in private hands and is rarely exhibited, so the opportunity to glimpse this heroic creature should be grabbed before it returns to its stall.

A cluster of Stubbs’s fellow Georgians – Turner, Gainsborough and Constable – will be on display at Gainsborough’s House, Sudbury in Suffolk (25 April – 11 October), as part of the celebrations around the 250th birthday of John Constable (11 June 1776). He can also be found at Christchurch Mansion, Ipswich, from March. Meanwhile, a wider display of early-20th-century outdoorsy painters feature in “British Landscapes: A Sense of Place” (Pallant House, Chichester, 30 May – 1 November) – Graham Sutherland, Eric Ravilious and Paul Nash among them. Landscape offered Winston Churchill a respite from politics, and time at the easel cleared his head of the fug of parliament. The evidence is on show in “Winston Churchill: The Painter” (Wallace Collection, 29 May – 29 November). If only today’s MPs were as good at politics as he was at painting.

Hurvin Anderson puts landscapes, often lush Caribbean ones that acknowledge his Jamaican heritage, at the heart of many of his pictures. His atmospheric, slightly dishevelled work will be on show at Tate Britain (26 March – 23 August). A different sort of scenery will appear at Dulwich Picture Gallery with the first British exhibition of the early-20th-century Estonian painter Konrad Mägi (24 March – 12 July), whose Baltic views, often charged with symbolic intent, ripple with colour. But for joyousness and autumn warmth, “Painting the French Riviera” will fill the Royal Academy’s galleries with hot shades as it explains why, from the 1870s, artists such as Matisse, Cézanne, Paul Signac, Monet and Bonnard headed south (2 October 2026 – 31 January 2027).

Long before artists actively sought to be a bit odd, William Blake was showing the way. His visions are given full rein in “William Blake: The Age of Romantic Fantasy” (National Gallery of Ireland, 16 April – 19 July). Other non-conformists include Richard Dadd, the father-murdering painter of fairy scenes and maniacally intense portraits (“Richard Dadd: Beyond Bedlam”, Royal Academy, 25 July – 25 October). The naive, folk painter – and former fisherman – Alfred Wallis captivated Ben Nicholson when he came across his seascapes in St Ives in 1928. What he and other avant-garde painters found in them is explored in “Alfred Wallis: An Artists’ Artist” at Pallant House (21 November 2026 – 11 April 2027).

Euan Uglow was another painter who did his own thing, and the nudes and still lifes of this meticulous postwar artist are the fruit of long looking and a curious empirical method (“An Arc from the Eye”, Milton Keynes Gallery, 14 February – 31 May). His contemporary Lucian Freud was also a slow painter – to the chagrin of his subjects, forced to endure innumerable sittings; his methods are laid bare in “Drawing into Painting” (National Portrait Gallery, 12 February – 4 May).

Never a year goes by without a flurry of Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood exhibitions, and this year’s roster includes “Pre-Raphaelites: Art and Poetry” (Laing Art Gallery, Newcastle, 17 October 2026 – 13 February 2027), “A Call to Art: William Morris and the Pre-Raphaelites” (Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 23 October 2026 –3 May 2027), and “William Morris: Common Paradise” (Whitworth, Manchester, 12 December 2026 – 14 November 2027). Morris, the great social campaigner, would surely have approved of the spirit behind “Comrades in Art: Artists against Fascism” (Towner, Eastbourne, 7 May – 18 October), a look at the ornery and principled painters of the Artists International Association, from Laura Knight to the unfortunate Percy Horton, who saw what was coming with the rise of militant nationalism.

Connoisseurship, patronage and therefore power is the theme of “Cosimo I de’ Medici: Art and Dynasty”, an imaginative exhibition at the Wallace Collection (18 November 2026 – 21 March 2027). Duke Cosimo (1519-74) was the epitome of the cultured Renaissance prince, and the products of both taste and riches will be shown through objects he owned, from ceramics and swords to painting. To prep, use up any spare air miles and head to Florence for more Medici, and combine the trip with a visit to “Rothko in Florence” (Palazzo Strozzi, 14 March – 23 August), the stuff of dreams.

Even that, however, might not top “Metamorphoses” (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 6 February – 25 May, then at Galleria Borghese, Rome, 22 June – 20 September). Titian, Correggio, Cellini, Caravaggio, Rubens, Rodin, Brancusi and Magritte were among the artists who responded to Ovid’s great poem with dazzling works of their own: a poem about transformations inspired transformative art.

[Further reading: Photo books of the year 2025]

Content from our partners

This article appears in the 07 Jan 2026 issue of the New Statesman, What Trump wants