The Manchester-based artist Louise Giovanelli’s career has been in the ascent ever since she was one of the stand-out artists in the seminal painting exhibition Mixing it Up: Painting Today at the Hayward Gallery in 2021. She was snapped up by the blue-chip gallery White Cube in 2022 (which co-represents her with Amsterdam-based Grimm) and is now having her first major institutional solo show, A Song of Ascents, at the Hepworth Wakefield in northern England.

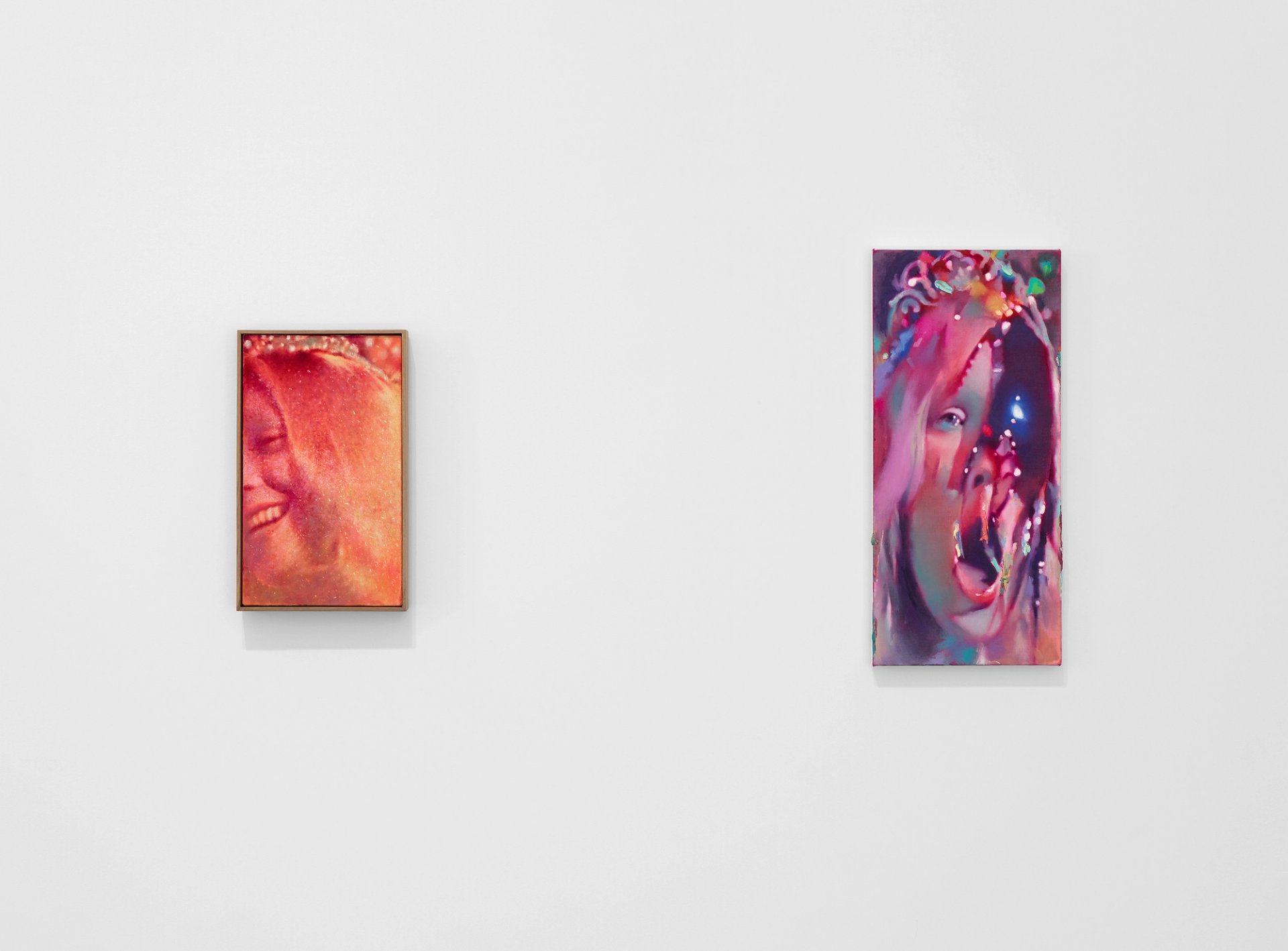

In her depictions of reflective surfaces, shimmering hair, and the type of heavy velvet curtains found in old working men’s clubs, Giovanelli treads the line between bleak mundanity and spiritual revelation. In one picture at the Hepworth—rendered in hazy analogue tones that make us doubt the reality of what we see—we wonder whether a young woman is waiting to receive Holy Communion, wildly intoxicated or lost in orgasmic abandon. Giovanelli’s gift lies in identifying and complicating our all too human desires for heightened states of consciousness, whether they are base or profound.

“They are seductive to look at but the audience can’t have them because the curtains reject everything—they will never open”: Giovanelli’s 5m-wide Prairie (2022) is one of several curtain paintings in the show Photo: Ollie Hammick; © White Cube; © artist

The Art Newspaper: What does your exhibition title A Song of Ascents refer to?

Louise Giovanelli: It’s taken from one of the penitential psalms, used in Catholic, Jewish and Lutheran liturgies. It also inspired Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis, and I suppose I was thinking about many of the same ideas as him, while he was locked away in prison for loving someone he shouldn’t have. Wilde talks about himself as being a Catholic who does not believe, but he is spiritual: the idea of ascension, of reverie, and reaching a higher level, all felt fitting.

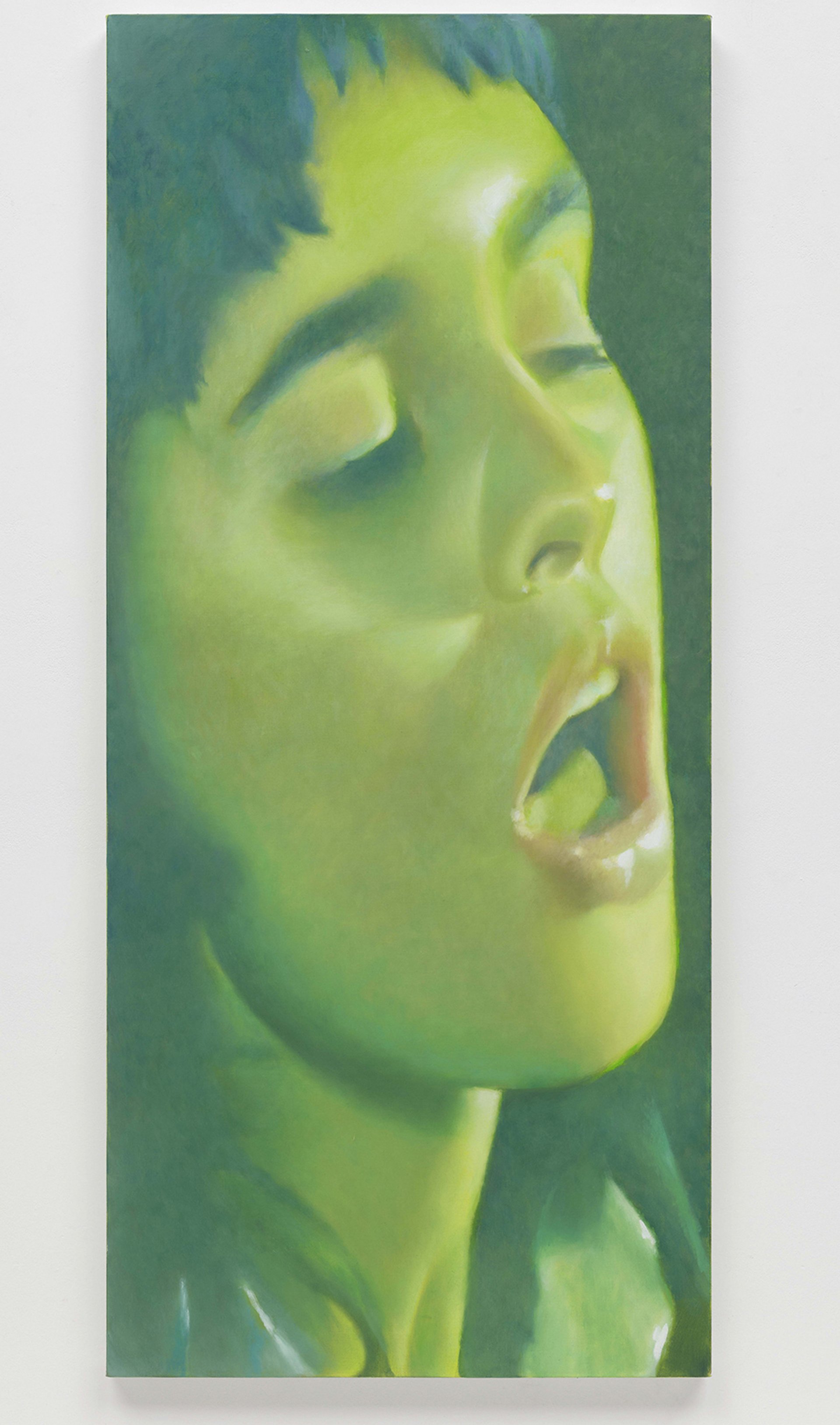

It is intriguing that many of your works have this Catholic element. Some refer to erotic open mouths that are actually about the taking of communion or refer to the medieval auto-da-fé—the burning of a heretic by the Spanish Inquisition. How do you find new ways to approach these ancient images and iconographies?

Well, I was raised a Catholic—my mum is Irish and my dad is Italian—but I would call myself a Catholic-atheist now. Growing up, I spent a lot of time in churches and I did confirmation, but then had a real rejection of it in my more rebellious teenage years, when I used to sit and read [Richard Dawkins’s] The God Delusion in church. It’s ridiculous now when I think of it, and it has obviously made an imprint, because I’m coming back to it in visual form. Over the past few years, I have looked to reimagine those ancient ideas of reverie and revelation alongside the contemporary world by connecting the dots through time to those secular rituals that we have today, around the saturation of icons and idols and forms of worship. The human instinct has not changed at all, but the phenomena have; the desire is there, but the object of that desire has been transformed.

The Smiths’ frontman Morrissey sang about how the pub wrecks your body while the church wants your money. In the catalogue for the show, there are two extraordinary collaborations. One is an enigmatic prose-poem by Helenskià Collett, the landlady of your favourite bar. The second is a kind of pub quiz by Charlie Fox, which is inspired by a series of yours that responds to the Carrie horror film, with clearly no “right” answers. How did these come about?

You’re spot on. The pub or the bar are also places of worship, of course; they are places to imbibe, to get away from regular life, to find a new community. Because of the curtains and the tinsel, people always think that I grew up with working men’s clubs but I didn’t, actually. When I moved to the north when I was 18 these places really fascinated me. They contain promise and theatricality, where anyone can have their moment, and I’m drawn to the democratic character of these clubs and of community centres. My fascination with curtains spans high and low culture: sometimes they are extravagantly performative venues with lots of money behind them. I was so pleased with the contributions in the catalogue. Charlie’s text is ambitious and a fantastic concept, and Helen’s contribution is more like abstract or absurdist poetry. We’ve only really just collided this year, but she is an artist in her own right.

Giovanelli’s Entheogen (2023) Photo: Michael Pollard; © DACS; courtesy of the artist

Helen is also the subject of a work in the exhibition, The Painting’s Landlady (2024). Lots of your images are filched from documentaries or pulp films, but here we have someone of importance to you. How does that relationship to your subject change?

It’s the first time that’s happened. I never make self-portraits, and up until now I have never made portraits of anyone I know. What I find interesting about Helen’s portrait is that her eyes are looking out, quite confrontationally, from the painting. I never do that, because as soon as you have the eyes meet the viewer, then it becomes a portrait, there and then. I never like to have that interpretation, and so if you have the eyes averted, it sets a different tone. Helen feels like a bit of an alter ego to me, she can do things that I can’t. On my opening night at the Hepworth, she created a tower of Martini glasses and performed her Surrealist poem for the guests. This felt true given that the bar she runs in Manchester is a kind of living artwork, which has in turn inspired my work.

One aspect of your practice that I think resonates with many people is its sheer difficulty. You paint things that are hard to paint: hair, curtains, glassware. Why make it so tough for yourself?

I am drawn to fabrics and reflections and glass, as well as shiny golden colours, and I’ve always been attracted to the challenge and to the alchemy of those things. I used to challenge myself with the question: is it possible to do this with paint? And of course it is, it always is, because I’ve seen proof in the paintings throughout history where it’s been achieved! Nevertheless, I’ve often thought about how that is possible with what is essentially coloured mud. I’ve always been surprised by how people go nuts for the curtains: yes, they are seductive to look at, but importantly the audience can’t have them because the curtains reject everything, and especially people, ultimately. Given how flat they are on the surface, they act like a kind of barrier because they will never open.

That is true. But there is this wonderful moment in Decades (2024), a diptych, where if you look closely, almost imperceptibly, the sides of the painting are coloured, and so it has the effect of seeing through into the unknown, in between the paintings, like a tiny aperture.

It’s interesting that you spotted that. I often put a colour down as the underpainting, and then the painting carries on and develops on top of that, but the underpainting is important for tonal value. And so even though it was a greyscale painting in silver, you needed a warmth coming through, so it had to be this ochre colour that you’re seeing, and you only see that through the gap, and that’s only because it’s made of two panels. What you’re seeing there is the very first layer, and I like that because it’s the first mark of something, an origin point that takes you beyond.

Giovanelli’s Auto-da-fé (2021, left) and Altar (2022) Photo: Michael Pollard. © DACS 2024. Courtesy of the artist, White Cube and Grimm

With Ian Hartshorne and Alice Amati, you’ve set up the Apollo Painting School for emerging artists. It’s an important intervention given the slow, and then sudden, demise of the English art school over the past decade. What have you learnt from setting it up?

We were a little apprehensive but the first year of Apollo was a great success, and we had a brilliant inaugural cohort: Ally Fallon, Isaac Jordan, Deborah Lerner, Hannah-Sophia Guerriero and Isobel Shore. The idea is that we have two months together, based out of my studio in Manchester, with guest lectures from artists and industry professionals, and then we go for all of August to Latina in Italy for the residency.

We are trying to fill the gap that we feel exists for arts education in the UK. Having been integrated into universities, art schools are now simultaneously too big and too weak, they’re too expensive, and they don’t have enough studio provision nor enough tutor time. Ordinary students can’t afford to go. We have a means-tested funding model at Apollo where artists earning less than £40,000—and so all of them—do not need to pay. It’s more like the Royal Academy Schools system, or the Städelschule system in Germany, and we wanted to pick those students who it would mean the most to. Ian, Alice and I all met in Manchester, and we have such a connection to the city, and there’s a zeitgeist atmosphere for painting there now.

Did you approach your exhibition at the Hepworth in a similar spirit? Did you want to do something different?

Yes, for sure. With commercial shows, such as those with my galleries Grimm and White Cube, you can be a bit bolder in terms of the concept, but when it came to the Hepworth, I had to be honest that many audiences would be arriving [at] my work for the first time. I had to introduce myself. We made a conscious effort to show five distinct series, including new paintings and some loans, about half each. Even though we were showing those five distinct series, one aspect that we wanted to bring out was the slight conversations and gestures between paintings, old and new, and the uncanny repetition of subjects like open mouths, curtains and images crafted from old B-movies. I use these anchoring devices like I might bang a drum: I’m weaving a story and want the audience to have something familiar that they can grip onto. I want people to walk around the show, stop, and ask: “Oh, hang on, did I see that there?” It creates a psychological tone, which I enjoy.

Biography

Born: 1993 London

Lives and works: Manchester

Education: 2015 BA, Manchester School of Art; 2020 MFA, Städelschule Frankfurt am Main

Key shows: 2017 Warrington Museum and Art Gallery; 2019 Manchester Art Gallery; 2021 Hayward Gallery, London; 2023 Moon Grove, Manchester; 2024 He Art Museum, Foshan, China

Represented by: White Cube and Grimm

• Louise Giovanelli: A Song of Ascents, The Hepworth Wakefield, UK, until 21 April