In one of the final rooms of ‘Vivono: Art and Feelings, HIV-AIDS in Italy. 1982-1996’, at Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci in Prato (through 10 May 2026), a gentle army of off-white sofas invites visitors to sit and absorb the words of Nino Gennaro, the artist, activist and poet whose writing is projected onto the surrounding walls (old photographs additionally appear on some of the furniture via a slide show). The space is loosely modelled after Gennaro’s own living arrangement, in the home he shared with his chosen family of community-minded artists until his death, from AIDS in 1995, which he described in personal notes from the 1980s as ‘a place to make mistakes but also to get things right, a place to heal but also to get sick…to die but also be reborn, a place where everything is allowed…’

‘You enter the house, and in literally each corner there is a sofa,’ shares curator Michele Bertolino, sampling the upholstery the morning after the show opened to collaborators and contributors, press, family, and friends of the museum. ‘It’s incredible because the sofas are always busy; it means being cosy and having the possibility to stay, to speak together.’ Gennaro’s friends still live in the same house in Palermo, where his work, tied to the idea of affection as recognition and care, remains, and which Bertolino visited often during the making of the show; each time, his hosts put him up in the artist’s old bedroom.

Nino Gennaro, Autoritratto, 1994

(Image credit: Part of a letter to Massimo Verdastro. Courtesy Massimo Verdastro)

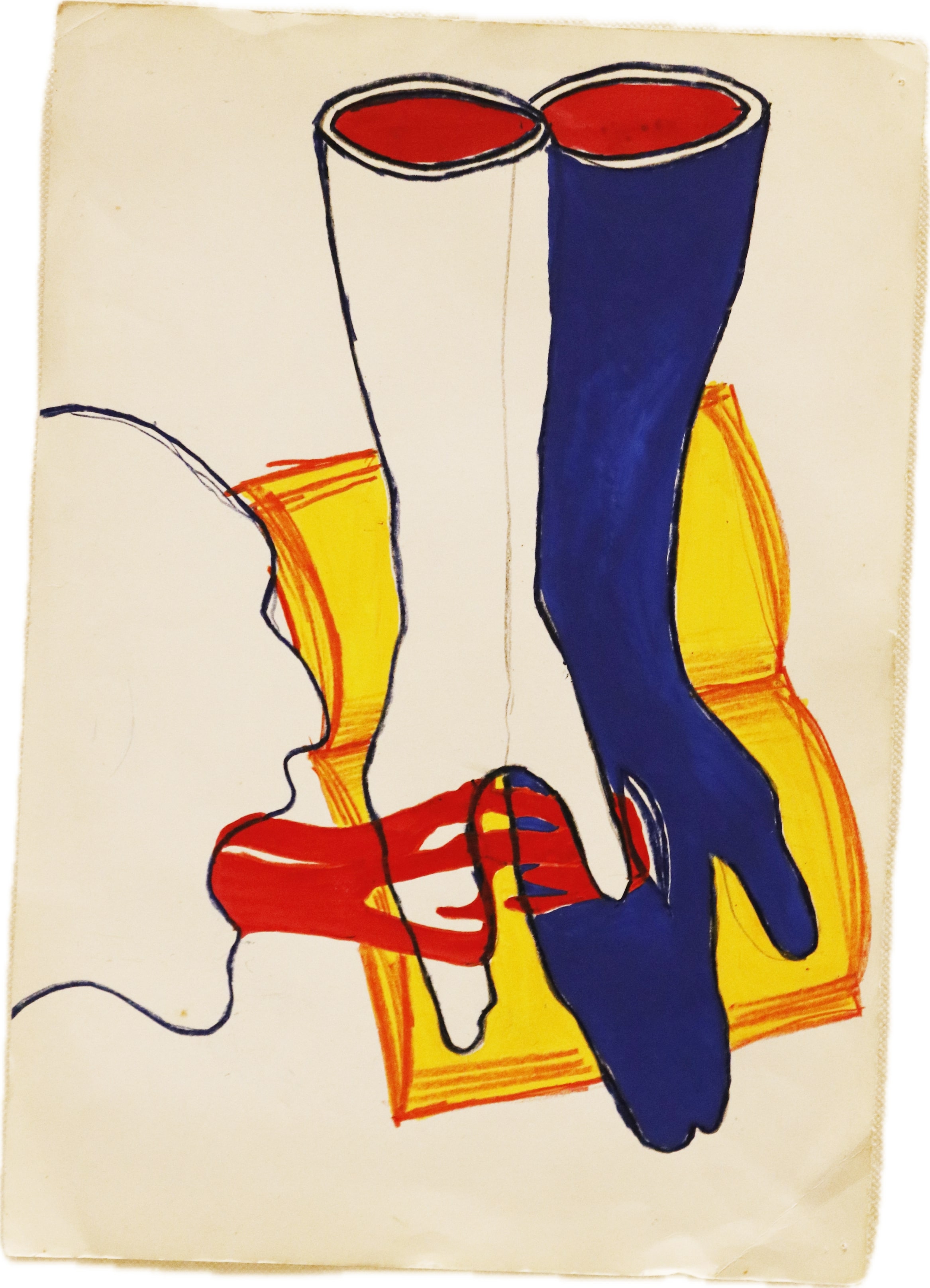

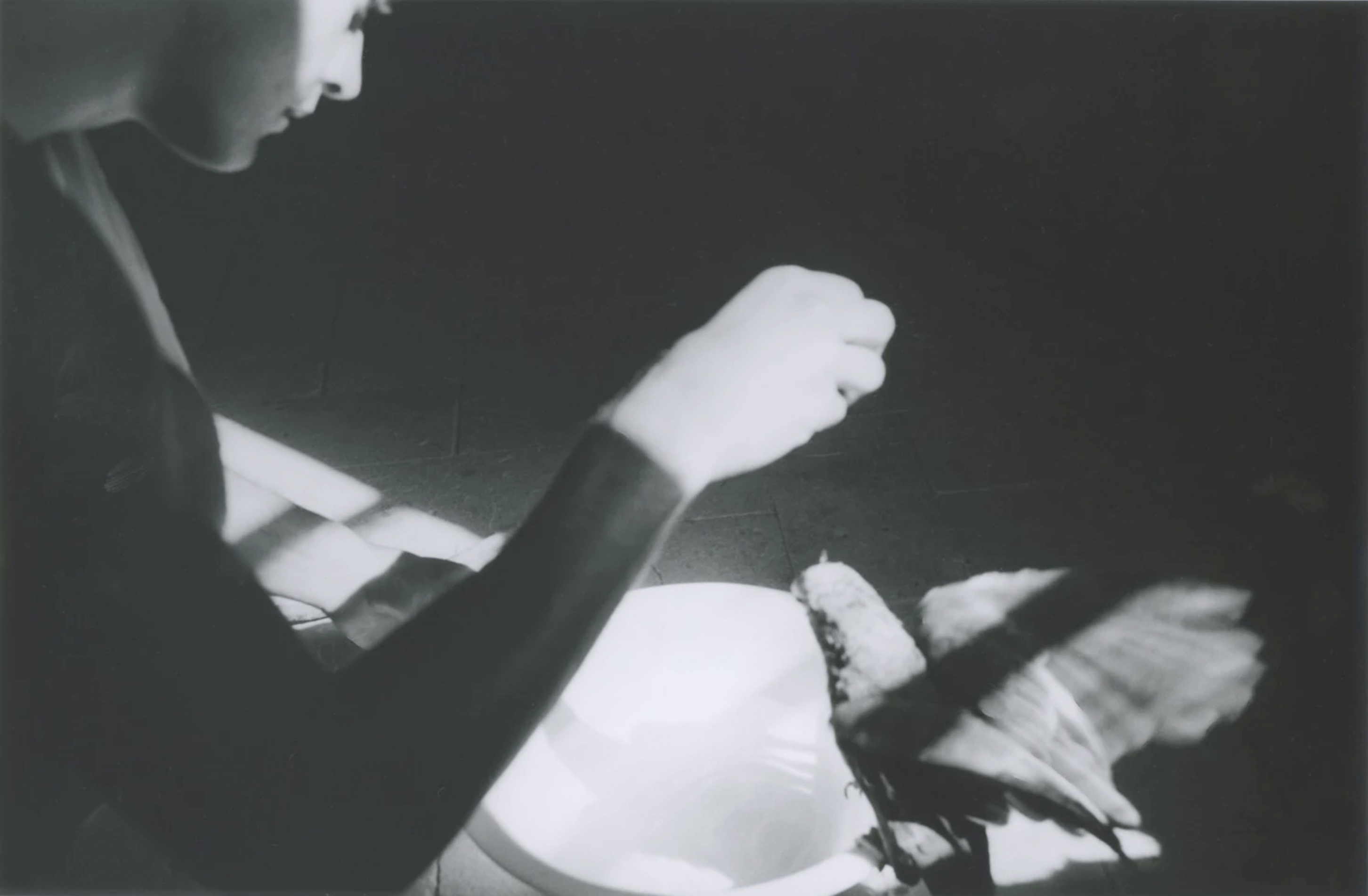

Francesco Torrini, Senza titolo, 1992-1993

(Image credit: Courtesy Alberto Torrini)

Gennaro’s is one of three monographic spaces that underscore the gravity of the wider show, each consciously developed by the curator’s friend, the architect and exhibition designer Giuseppe Ricupero (the other two rooms focus on Patrizia Vicinelli and Francesco Torrini). ‘These artists give a specific hint to the way in which the HIV-AIDS crisis was approached in Italy and I think, as a first show discussing this, sum up the issue,’ says Bertolino. The show’s moniker moreover, is direct in its communication: ‘vivono’ translates to ‘they live’, and the dates relay the earliest recorded case of AIDS in Italy, and the year HAART therapies were introduced, in Vancouver, at the XI International AIDS Conference.

A response to the silence Bertolino identified around HIV-AIDS in Italian culture – particularly amongst those championing foreign art made in a similar context – the show was constructed through discussions together with research the curator had begun for an earlier photobook project. ‘It came out of necessity,’ he explains today. ‘It’s a conversation that is going on [globally], and in Italy we are not addressing the issue.’ Thinking communally, Bertolino worked with a committee that included the collective Conigli Bianchi, activists Valeria Calvino and Daniele Calzavara, and Ida Panicelli, the museum’s artistic director between 1993-94. ‘They took my hand and let me in, this guy coming from contemporary art, asking personal things about their life,’ recalls the curator. ‘They really helped me understand and navigate this history, as it’s not a history I lived.’

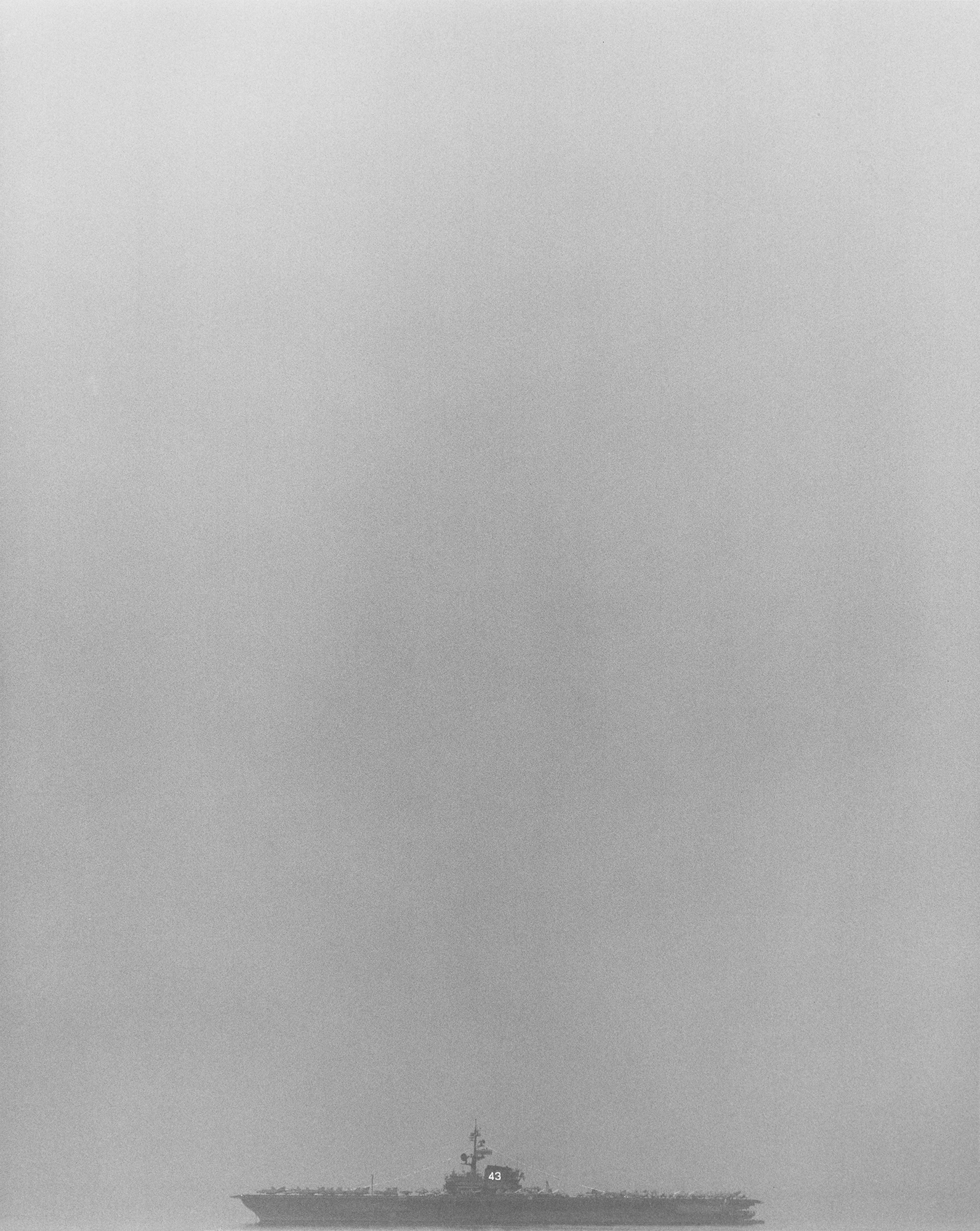

Robert Mapplethorpe, Coral Sea, 1983

(Image credit: © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. Used by permission.)

Hervé Guibert, L‘oiseau, Santa Catarina, 1982

(Image credit: Courtesy Felix Gaudlitz)

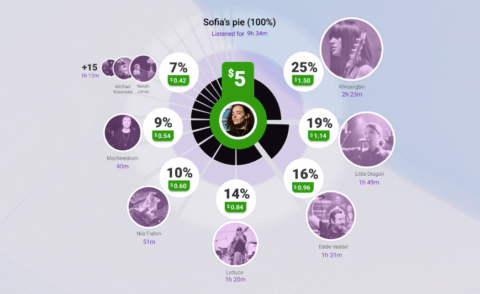

Consisting of nine rooms in total, the show is orchestrated primarily around Italian artists, while several British and American names also appear (Robert Mapplethorpe’s quietly brooding Coral Sea (1983) is surrounded by ample white space, while Derek Jarman’s Pontormo and Punks at Santacroce, from 1982, plays nearby to The Pope and the Penis, the bold text-based work previously exhibited at the 1990 Venice Biennale by New York collective, Gran Fury). A specially commissioned Roberto Ortu film introduces the show, and a vast collection of painting, illustration, sculpture, video, photography, and poetry follows. Paramount for Bertolino however, are a series of worktables made up of archival materials such as pamphlets, articles, posters, campaigns by Moschino and United Colors of Benetton, and recent works by Milan’s Tomboys Don’t Cry collective.

‘I wanted it to be meaningful and present, so we had conversations about what it means to collect and preserve, how we build a memory when there is no memory,’ says the curator. Formed around themes, as opposed to chronology, labels include stigma, care, time, shit and celebration; ‘shit’ was a suggestion from Calvino notes Bertolino, acknowledging the term’s complexity. In an essay from the show’s accompanying book, Reader, Calvino expands on the word’s significance, alluding to her own experiences and drug use amidst the social and cultural shift that occurred in the country in the late 20th century, as Italy moved into neoliberalism. ‘The 1980s were shitty years,’ she writes. ‘Shitty in the sense that they digested and discarded everything that the 1970s had been…the years of marches, collectives, self-awareness groups, counterculture…’

Bruno Zanichelli, L’impossibilità di distogliere lo sguardo -Dipinto autofruente, 1989

(Image credit: Courtesy Felix Gaudlitz)

Indeed, much of the work presented at Centro Pecci was made against this backdrop, and yet Bertolino and Ricupero were determined to foreground a sense of lightness within the show, honouring the desire to love and embrace joy that existed in tandem with the extreme grief and political landscape of the time. Writing after his own diagnosis in the 1980s, Gennaro once suggested that ‘it is never a personal matter,’ indicating the comfort sustained from the relationship between HIV-AIDS and creating a shared narrative.

The sentiment is partially echoed in the responsibility Bertolino felt while putting ‘Vivono’ together he says. ‘A lot of people trusted me in a very sincere and immediate way. Behind this work there were people, life experiences – for some people, it was years since they had gone back to the works, or talked about their partner or son,’ he shares. ‘The subtitle of the show is “art and feelings”, and I was really not sure about this, but it is a show about feelings – made through feelings, constructed because of love. And I would love it to be the opening up of a conversation that is not present in Italy. Luca Starita [who also contributed an essay to Reader] will publish in February, a book on literature and poetry and HIV-AIDS in Italy, so things are happening. It’s a collective effort.’

‘VIVONO. Arts and Feelings, HIV-AIDS in Italy, 1982-1996’ at Centro per l’Arte Contemporanea Luigi Pecci, Prato, until March 1, 2026