Hilma af Klint’s reputation has recently had a renaissance, securing her legacy as the first western artist to create truly abstract works, half a decade before Wassily Kandinsky, who was previously considered to be the world’s premier abstract artist. However, this couldn’t have happened had the artist not given strict instructions to her family about the future of her artworks after her death.

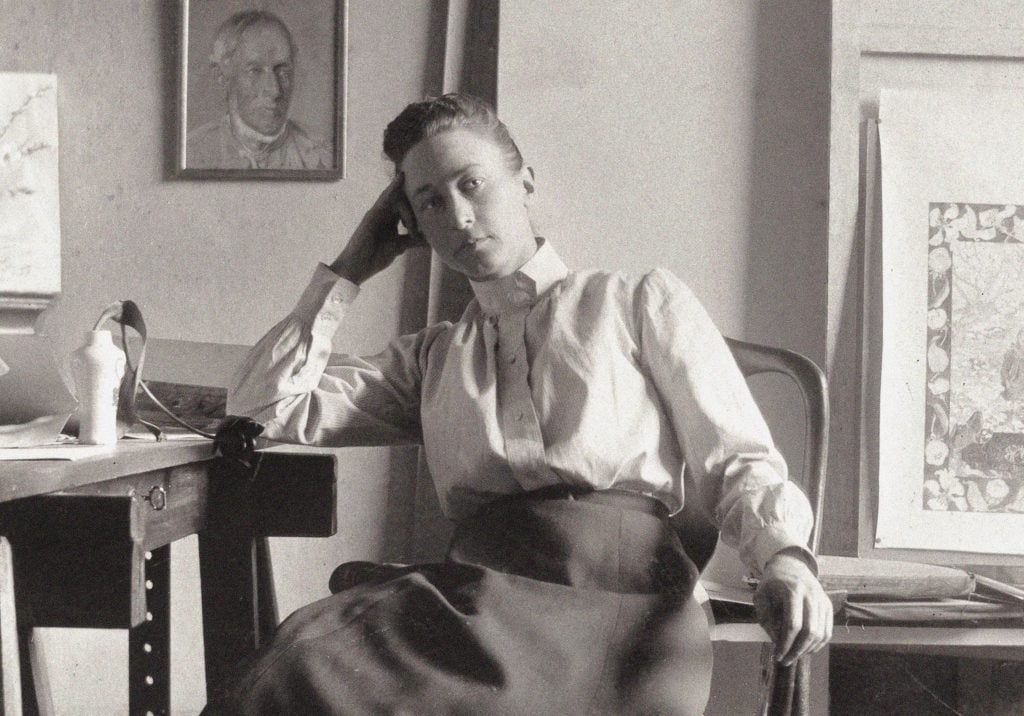

Af Klint was born in Solna, Sweden in 1862 and graduated with honours from Stockholm’s Royal Academy of Arts in 1887. She studied traditional portraiture and landscape. After the death of her sister in 1880, af Klint became in tune with the spiritual realm, which guided her abstract practice for the next 60 years.

Hilma af Klint, Group IX/SUW, The Swan, No. 12 (1915). Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images.

She headed “The Five”—a group of five female artists and poets harnessing spiritual teaching and psychography to create their work. The group met each Friday for a decade, creating work and conducting seances. The group made “automatic drawings” guided by the spirits they contacted. Of these artworks, af Klint said “the pictures were painted directly through me, without preliminary drawings and with great power”. During a seance, af Klint was contacted by an entity called Amaliel who told her to paint the “immortal aspects of man”, leading her to create 193 paintings—known as the Paintings for the Temple—over the course of nine years.

When the artist died pennilessly in 1944 following a traffic accident, she had stipulated in her will that her artworks weren’t to be exhibited until 20 years after her death. The artist believed that it would take two decades before her work could be fully understood, and she was right: when the paintings were offered as a donation to Stockholm’s Moderna Museet in 1970, they were rejected. It would take several more decades before af Klint’s position as a pioneer of abstraction would be truly celebrated.

Hilma af Klint in her Hamngatan Studio (1895). Image by Fine Art Images / Heritage Images via Getty Images.

There had been another voice advising af Klint that her work needed to be appreciated only after a delay, too. In 1908 the occultist and architect Rudolf Steiner saw her paintings while he was a lecturer in spiritual science in Stockholm. He told the artist “no one must see this for 50 years.”

She had 1,200 paintings, 100 texts, and another pages of 26,000 notes stored away, which were passed to her nephew, Erik, an admiral in the Royal Swedish Navy. After their rejection by Moderna Museet, Erik af Klint started the Hilma af Klint Foundation in 1972 in order to cement his aunt’s legacy.

Hilma af Klint, Group X, No. 2, Altarpiece (1915). Found in the Collection of Courtesy of Stiftelsen Hilma af Klints Verk. Photo by Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Speaking to the Guardian in 2016, Johan, Erik’s son, reminisced about his father storing the mammoth collection of work before af Klint’s house and studio were due to be burned down by the farmer who owned the land: “he built wooden crates and rolled everything up – 1,000 or more paintings were stored in our attic. We had a tin roof. Imagine! In summer it was sometimes 30 degrees, in winter minus 15. Terrible. It was a miracle the paintings survived.”

Af Klint’s works were exhibited for the first time at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in 1986 in “The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1850-1985,” a group show curated by Maurice Tuchman. The exhibition was also credited with introducing the work of Agnes Pelton to mainstream audiences for the first time. More recently in 2023, af Klint shared a mammoth show at London’s Tate Modern with the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian. According to the exhibition guide, “Although they did not know each other—or of the other’s work,” the “Forms of Life” show explored, “how they both developed the possibilities of abstract art, moving away from the conventions of representation they were taught”.

What’s the deal with Leonardo’s harpsichord-viola? Why were Impressionists obsessed with the color purple? Art Bites brings you a surprising fact, lesser-known anecdote, or curious event from art history. These delightful nuggets shed light on the lives of famed artists and decode their practices, while adding new layers of intrigue to celebrated masterpieces.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: