The name of Paolo Cirio’s new exhibition, AI Attacks, is knowingly ambiguous. Is he attacking AI, or is it attacking us? In reality, it’s somewhere in between. Presented at Foam in Amsterdam, the exhibition brings together four of his projects – including one new work – that collectively unpick AI and how it’s leveraged against individuals and societies. He does this with challenging, provocative works that span photography, text, moving image, and, yes, generative AI.

Cirio, an artist, activist and hacker, describes himself as a “kid of the cyber punk scene from the end of the 90s”. As the internet took off, and with it Silicon Valley, the tendrils of his career began to form – particularly the hacker part of his practice as he rooted under the bonnet of those tech companies before they became watertight, “something that’s now much harder”.

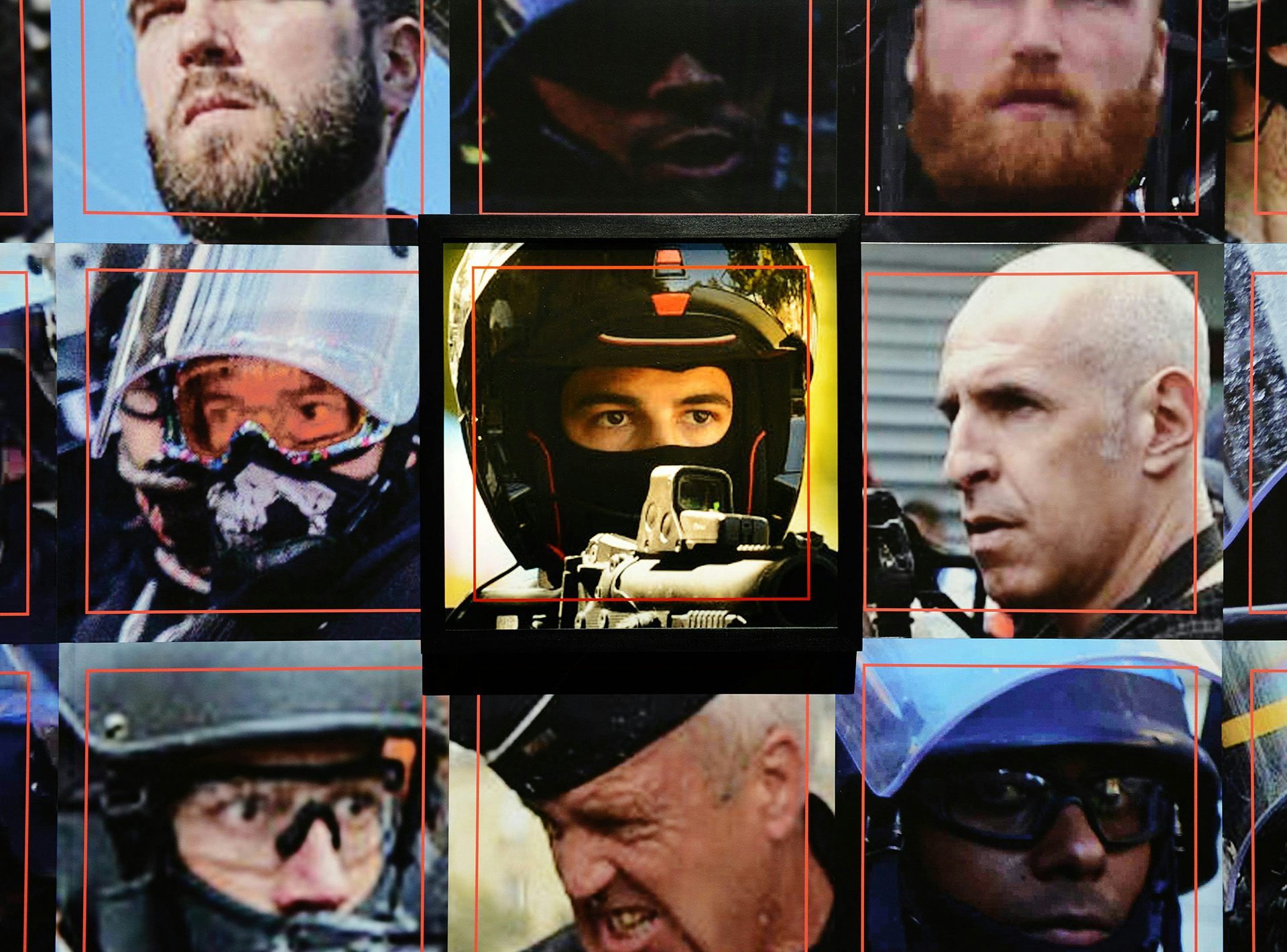

His first project involving AI came out in 2011, where he delved into facial recognition technology (FRT). Since then, facial recognition has only become more complex and pervasive as data glides under the table between all too powerful actors in both state and private sectors. It has remained a focus of his work ever since, namely in his contentious project Capture, in which public images of police officers were processed with FRT and shared on a microsite.

The identities of more than 4,000 police officers in France were then established through crowdsourcing, and their identities were flyposted around Paris. “That was actually all a provocation to show how dangerous facial recognition can be and how an attack that can be done against the police can be done against anyone, because AI is a sort of weapon,” Cirio says.

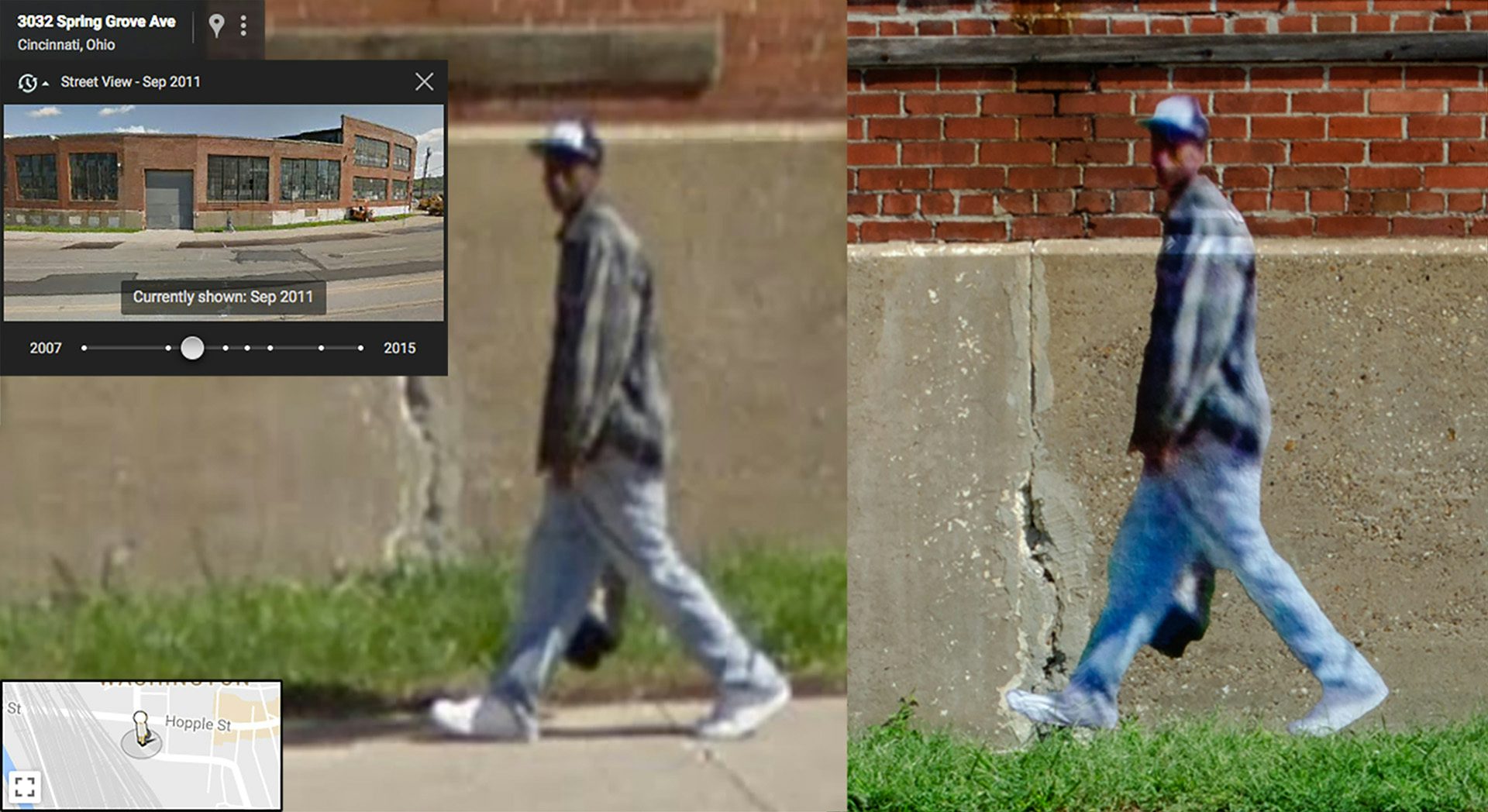

It lies in contrast with other projects of his, such as Street Ghosts, which features members of the public seen through Google Street View, or Obscurity, which involves mugshots of people who have been arrested in the US. As those titles suggest, the bodies and faces are disguised by Cirio. How does he decide where the boundaries are in his work? Who is entitled to anonymity?

“It’s probably hacker ethics in a way, so in some cases, it’s necessary to protect the privacy of some individuals, especially [the] masses, and in some other cases, as an activist, I want to expose people … and in that case, the details are very visible,” he explains. In the exhibition, the exposed police officers of Capture are juxtaposed with Obscurity, “where in fact I blur and I protect the privacy of ‘criminals’”.

In some cases, it’s necessary to protect the privacy of some individuals, especially [the] masses, and in some other cases, as an activist, I want to expose people

“It might sound like a contradiction, but it’s not. It’s actually trying to define and pinpoint the cases when we need to expose [someone] and who can be exposed, too. So police officers for instance, they are not public figures, but they are public servants, so when they act in name of the state, they are public figures in a way. And nevertheless, those pictures were taken in a public space. So I really consider the context of that visual material,” he says.

“I also consider the ethics of what I’m doing, and I also consider the context: how I’m doing [something], for how long, where I’m exposing it, what is really the aim. There are many details that I consider when I do this practice.”

The Capture work dovetailed with Cirio’s 2021 campaign to ban FRT in Europe, which garnered 50,000 signatures on a petition and was acknowledged by the European Commission (though no outright ban followed). Yet when he first displayed Capture in France, it also attracted the attention of police officers and their unions, and escalated to the French interior minister of the Macron government, which eventually instructed him to remove the online database.

“To this day, it’s basically impossible to show this work in France,” he says. AI Attacks marks one of the first times the entire installation has been displayed in Europe since the outcry, and certainly requires a degree of willingness from its host to get stuck into the messy sphere of AI and the ethics around it.

It comes as part of Foam’s timely programme Photography Through the Lens of AI, which also includes a group exhibition and an issue of its magazine interrogating the technology. There are obvious challenges in an institution wading into a fast-evolving space, as indicated by the comparative silence on the subject of AI from other prominent photography museums around the world. However, the Foam team note in the editor’s letter that “as a museum and magazine dedicated to photography, we can’t ignore new currents, and see it as our responsibility to unpack the ‘black box’ that is AI”.

Cirio has incorporated generative AI in his new work, Resurrect, which uses ChatGPT and deepfake technology to reanimate four dead military figures, who despite being directly involved in colonial or fascistic regimes, remain celebrated in some circles. In the work, Cirio has them own up to the atrocities they committed or enabled.

“That’s an attack against, in a way, those figures, against the war, militarism culture, also because now those people are online saying their regrets, saying stories about their war crimes and so on,” Cirio explains. While people are concerned about AI-based disinformation, here he’s suggesting that “AI can eventually be used to say the truth that’s never been said”.

Whether or not people respond positively to Cirio’s work (it seems unlikely that it’s even the point of his practice), there’s no denying that he goes where a lot of artists won’t. While plenty of creatives are unpicking the machinations of AI, big data and Silicon Valley from afar, fewer get up close and personal. “I do believe that there is a bubble about it, and it’s not only the art world, but it’s particularly [present] in academia, which we all respect of course, but it does get detached from reality,” he says.

“I did notice that a lot, for instance, with the mugshots project. This problem, yes, is coming from the internet, the technology, but it’s also concerning the economic political context of where these people live, which is very concrete and sometimes it comes down to a particular corner or street or a particular county, where there is actual, real people.” How this technology is used is a symptom of wider structures that shape people’s lives on a very everyday level in myriad ways. “Artists and academics, they don’t much talk about the people that are affected. They don’t hang out with those people.”

Nonetheless, artists do have a significant role to play in showing how AI relates to systems, laws, and freedoms by showing exactly “how things could go wrong, how powerful a certain technology is, but also in a real practical way”. Some of those artists can even offer solutions, whether technical, legal or philosophical. “Otherwise you would have only the engineers trying to figure out something or you would have only the legislators trying to figure out something, and they come from very specific technical disciplines, which are lacking in creativity quite a lot.”

While Cirio is acutely aware of the dangers of AI, he believes that most preoccupations with the technology are focusing on the wrong issues. “It’s pushed this narrative of detachment with reality … the fact that AI is such a powerful tool that it will control us our even destroy humanity and so on. That’s a distraction from the physical problem, the everyday problem, that we all have.” (For the record, he believes that AI will “make us even busier and will create even more jobs”.)

Besides impending job uncertainty, and even the already pervasive issues around privacy and profiling, Cirio suspects that generative AI’s biggest dangers are connected to what makes it appealing: the ability to conjure imagined worlds. When combined with the addictive realm of social media, he suggests that our current echo chambers could evolve into something bigger, where people become more insular, more polarised, as they build a world for their worldview.

“What’s concerning is very similar to the social media paradigms, where social bubbles are created. Not just social bubbles, but personal realities, small realities, where people fall in and they get stuck, also because the algorithms are feeding people those realities. With generative AI, that will be even bigger.

“It sounds like a video game, but I think it’s already happening to some degree in social media. And it’s very addictive, actually, as we already know,” he says. “So I think that that’s a real problem for generative AI, more than the fact that there will be deepfakes – because, yes, there will be deepfakes. What concerns me is that people will fall inside those deepfakes like in a rabbit hole, and they will never be able to get out.”

Next Level: Paolo Cirio – AI Attacks is on display at Foam, Amsterdam until August 25. Photography Through the Lens of AI runs until September 11; foam.org