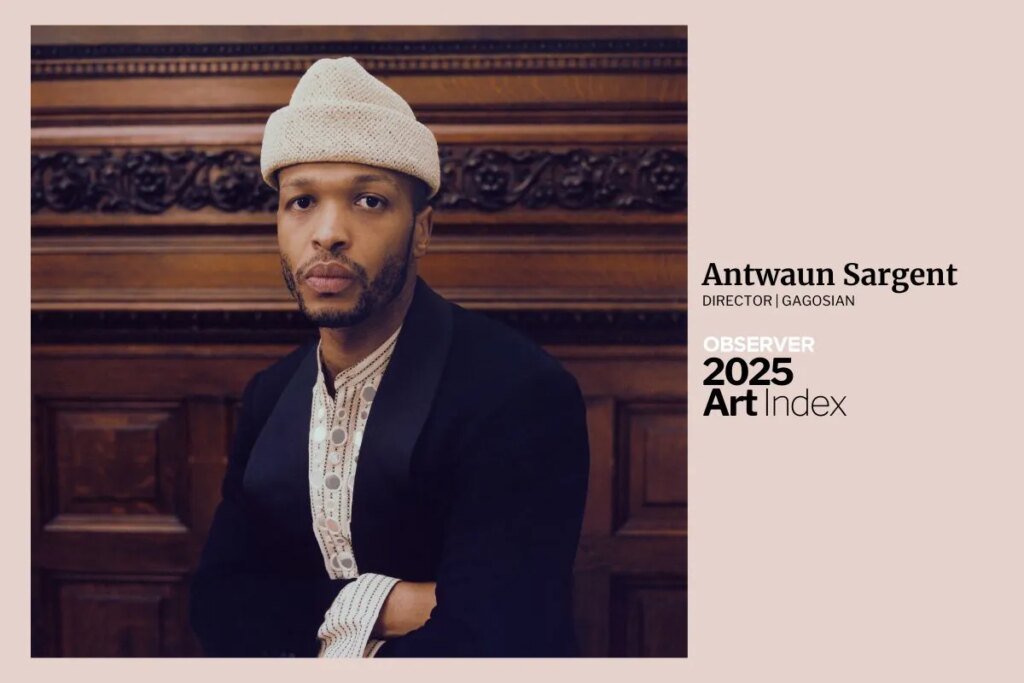

Antwaun Sargent, featured on this year’s Art Power Index, has built a career dismantling the art world’s old hierarchies and rebuilding them around artists. As director at Gagosian, he’s been dubbed the “Art Star Maker,” though Sargent rejects that label, insisting that success belongs entirely to the artists he champions. His philosophy is deceptively simple: believe in artists and do everything possible to bring their visions to life.

That ethos has shaped some of the past decade’s most notable exhibitions, from Virgil Abloh’s “Figures of Speech” at the Brooklyn Museum to “Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick,” the institution’s first solo show dedicated to a Black artist. Since joining Gagosian in 2021, Sargent has continued to push the boundaries of what’s possible inside the “white cube,” curating shows that center Black creativity and urging collectors and institutions alike to expand their understanding of cultural value.

A writer and curator in equal measure, Sargent’s influence predates his gallery work. Through essays in scores of publications like The New York Times and The New Yorker, and through books such as The New Black Vanguard: Photography Between Art and Fashion (which he authored) and Young, Gifted and Black: A New Generation of Artists (which he edited), he’s helped reframe how the world engages with the intersections of art, race and representation.

For Sargent, power in the art world is—and isn’t—shifting. True inclusion, he argues, requires generational commitment, while technology—from social media to A.I. tools—is transforming ideas of artistic authorship. Above all, he returns to his core question: how to keep putting more power directly into the hands of artists.

What do you see as the most transformative shift in the art world power dynamics over the past year, and how has it impacted your own work or strategy?

My main focus is to continue to make the best shows possible. The artists I work with at the gallery, Lauren Halsey, Rick Lowe, Tyler Mitchell, Cy Gavin and Derrick Adams, are focused on making great work, and my role is to support the production of that art. I will continue to focus on that, as we have seen great success. I am always asking: How do we help the artists make the best work possible? It’s the guiding question that has really allowed me and my team to support our artists in my most effective way. My only strategy is to believe in artists, which is to say I do whatever possible to make their visions reality.

As the art market and industry continue to evolve, what role do you believe technology, globalization and changing collector demographics will play in reshaping traditional power structures?

The evolution of the art world and its centers of power have been greatly exaggerated. The only thing I’m interested in is putting more power in the hands of artists.

Looking ahead, what unrealized opportunity or unmet need in the art ecosystem are you most excited to tackle in the coming year, and what will it take to make that vision a reality?

I still think the best way to encourage an art ecosystem I believe in is to create it. So, I’ll continue trying to broaden participation in every way, from the artists, the gallery show, to the collector and audience, who will encounter and thus be moved by the work.

You’ve been described as the “Art Star Maker.” Does that label resonate with you?

The success of an artist is wholly their own.

The art world sometimes celebrates inclusion rhetorically but struggles structurally. From your vantage point today, what tangible progress have you seen—and where are the most urgent gaps still visible?

The urgent question today is: will the art world keep its word? In 2020, a lot of promises and declarations were made around questions of diversity and representation. I hope the current situation only emboldens the necessary work of correcting the narrative to continue. I think the important thing to note is that this is long-term work, generational work: keep going.

You’ve talked about “expanding what’s possible inside the white cube.” What does that mean in practice—how are you reshaping the curatorial voice of one of the world’s most powerful galleries?

Look at the shows.

Has working within a mega-gallery altered your ideas about equity in the art world?

Nope. It is possible. More of us should want it.

The collector base for young artists of color has exploded, sometimes leading to market overexposure. What are your thoughts on the realities of balancing hype and stewardship?

I think young artists should work through the system and build careers over the long term. If they truly do that, then they will be fine.

Your written work continues to influence how people think about visual culture. How do your writing and curation inform one another in your practice?

My writing was about taking Black artists seriously and at their word. The decade of writing really informs everything I do. I think because writing requires a kind of sustained looking, and the more you look at art, the more it reveals its many possibilities. Deep looking rewards the viewer.

You’ve curated over 30 shows, from Virgil Abloh’s “Figures of Speech” at the Brooklyn Museum to “Barkley L. Hendricks: Portraits at the Frick.” Are there throughlines that connect these projects conceptually for you?

Not at all. I was interested in the fact that Black artists were making all these wonderfully diverse artworks, and I wanted to show that. I still do, that’s the thesis of my current job. There are no boxes. Black art is whatever the Black artist says it is.

Digital culture and social media have been central to your curatorial language. How do you see platforms like Instagram or A.I.-assisted tools changing the way we perceive authorship and artistic labor?

Before when I was using it a lot, social media, it was about trying to direct my audience toward the power of art. I was genuinely just trying to say to the audience, “This is great, go see it.” The current social media and rise of A.I. are very different from those early days. I hope we survive it.