In 1963 two artists opened their debut solo shows in London. Such was the hype surrounding one of them, Patrick Procktor, a flamboyant 27-year-old graduate of the Slade School of Art, that three quarters of his show at the Redfern Gallery in Cork Street had sold before it had even opened. The other was David Hockney. Both of them young and blessed with extravagant talent, they became firm friends – and the toast of the London art scene. “You couldn’t really mention one without the other,” said the art critic John, McEwen of the two. “It was like Castor and Pollux. They were the dandy art twins of the art world.”

This week an exhibition devoted to the work of Procktor opens in London. Spanning the years 1962-2002, it features paintings, watercolours and drawings from one of the great lost talents of his generation. For few people now remember the Dublin-born artist who moved to England at the age of four. At 6ft 5in, with a penchant for theatrical clothing and equipped with a rapier wit, he streaked like a comet through the creative circles of the 1960s. Yet he fell into critical neglect during the 1980s and after succumbing to alcoholism, lost almost everything in a catastrophic fire at his Marylebone flat in 1999. He died homeless and virtually penniless in 2003.

Procktor was of the generation whose childhoods were marked by the austerity of the Second World War. But where the bleak domestic interiors of the so-called 1950s Kitchen Sink School were redolent of the era of postwar rationing, art in the 1960s was young, witty, colourful, glamorous, reflecting the optimism of the modern world. The style was exemplified by “The New Generation: 1964”, a survey exhibition of 12 young painters, including Procktor, at the Whitechapel Gallery in the spring of that year. As Jonathan Miller wrote: “There is now a curious cultural community, breathlessly à la Mod, where Lord Snowdon and the other desperadoes of grainy blow-ups and bled-off layout jostle with commercial-art-school Mersey stars, window-dressers and Carnaby Street pants-pedlars. Style is the thing here – Taste 64 – a cool line and the witty insolence of youth.”

Also included in that Whitechapel show was Hockney, who first met and befriended Procktor in February 1962. Of their friendship he later said: “We simply had a lot of interests in common – painting, literature, and being gay, then. Because most people were in the closet at that time.”

Procktor suited the 1960s and the 1960s suited him. He became an integral member of the glamorous, and subsequently much mythologised circle that included the fashion designer Ossie Clark, Cecil Beaton, Celia Birtwell, and Peter Schlesinger. Fiercely intelligent, and immensely stylish, Procktor knew everyone and painted most of them, and his flat in Marylebone became both an artist hang out and a theatrical space, serving as both sanctuary and studio, the backdrop to his life and to many of his paintings. His portraits of the actor Jill Bennett and playwright Joe Orton are amongst the iconic images of the era. “He was a very stimulating friend. He had a very peculiar fantastical wit, which was always kind of bubbling away,” the stage director Anthony Page once said of him. “I’ve never met a character quite like him – he was like an 18th-century dandy.” Celia Birtwell remembered him at parties, “always looking fantastic, always wearing really clever, interesting, slightly Eastern clothes, which looked marvellous on that tall, slender figure. He would sometimes wear a fez, and peer down at you with that Giacometti head of his.”

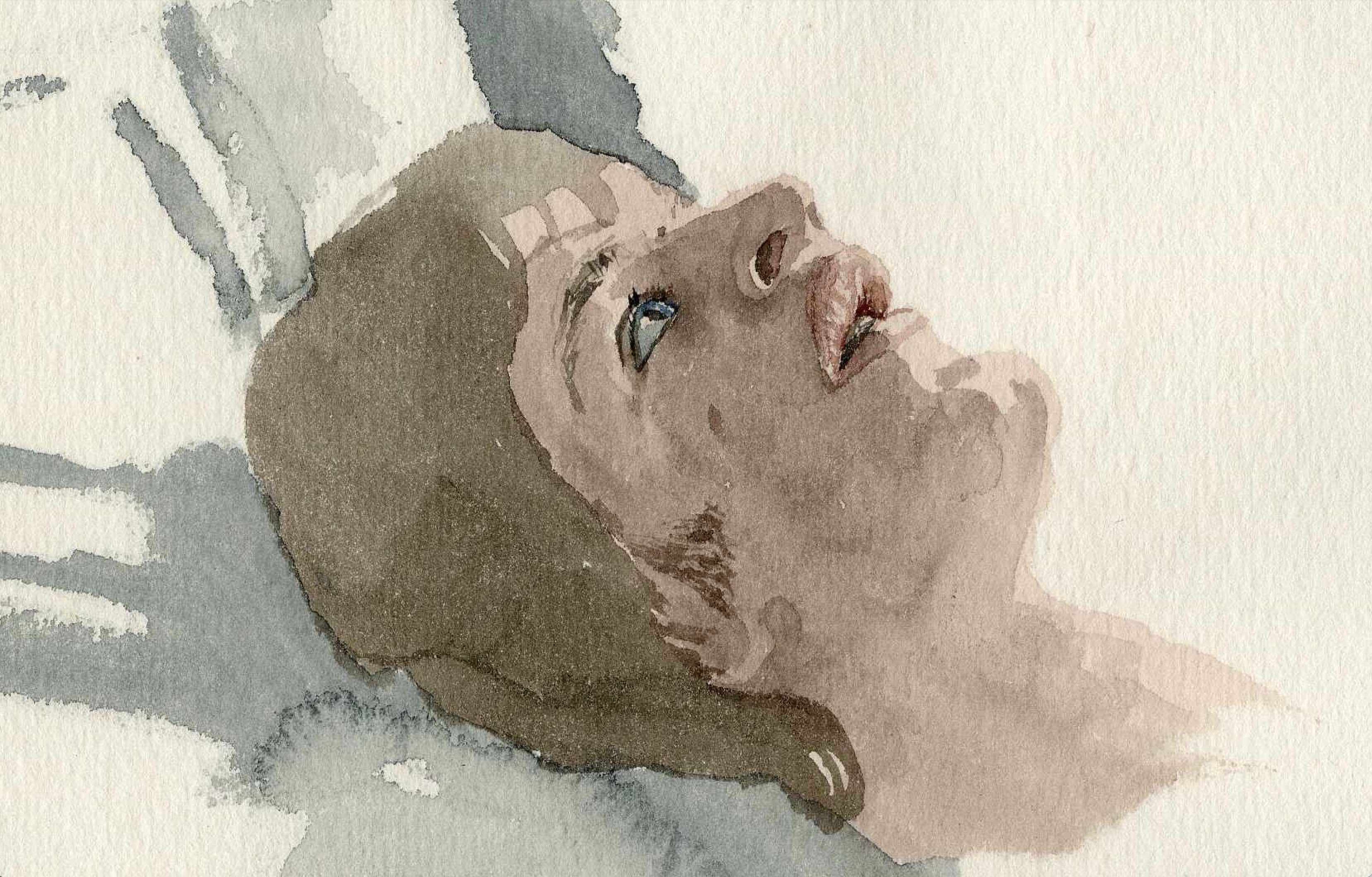

Procktor was soon to prove the most authoritative watercolourist of his generation. He began to fully explore the medium in the summer 1967, during a holiday in Europe with Hockney and Hockney’s boyfriend Peter Schlesinger. Frustrated by his own attempts, Hockney gave his box of watercolours to Procktor, who, firstly making portraits of his friends, took to them instinctively. Then, in the following year came an obsessive outpouring of watercolours, drawings and paintings on canvas, all portraits of one of Procktor’s great loves, the 22-year-old model and aspirant pop singer Gervase Griffiths. Several are included in the new exhibition, among them the watercolour “Limerick Head” (1968), a sensuous, near-forensic depiction of the young man’s face and head in close-up. Procktor went on to make oil paintings bearing the lightness and immediacy of his watercolours, such as “Waxy Bells” (1970), an ethereal landscape based on a watercolour made in India, which is also included in the show.

In 1976 the restaurateur Peter Langan opened his eponymous Brasserie in Mayfair in September 1976. It soon became the Café Royal of the period, attracting a glamorous international clientele. Langan cannily exchanged the art that adorned his restaurant for food; artists would “eat down” the worth of their pictures in meals, and the regular presence of celebrated artists whose work decorated its walls gave the place an invaluable cachet. Procktor and Hockney were the artists most associated with Langan’s, and synonymous with its success. Both produced menu designs, and in 1979 Langan commissioned from Procktor a Venice-themed mural for his upstairs dining room. By then Procktor had become renowned for his watercolours and aquatints of Venice, and his mural, a beautifully sustained panorama considered among his best works, covered all four of the dining room walls.

Yet as his friend and contemporary Hockney burned ever brighter on the international stage, Procktor’s star began to fade. Unlike Hockney, he had little enthusiasm for America, and his artistic roots were in English and European art. His one and only American solo show – in New York in December 1968 – was a commercial flop, and a severe disappointment. His overtly camp demeanour seeded doubts in some quarters about the seriousness of his deceptively felicitous art. Meanwhile, his gradual descent into alcoholism exacerbated a self-destructive streak, and Procktor often resorted to rudeness to art world figures and institutions that might otherwise have supported his career. At the same time he found himself out of step in the era of conceptualism and minimalism.

Moreover, like many gay men of his generation Procktor was conflicted about his sexuality, and felt pressured to conform. After the break-up of a queer relationship, he became close to his neighbour Kirsten Benson, a widow with two young children, who with her first husband had set up the fashionable Marylebone restaurant Odin’s. In 1971 she and Procktor began to live together, and in August 1973 they were married, with Kirsten already pregnant by him: their son Nicholas was born in the following January. “Kirsten was kind of a foil to him,” said the artist’s friend Christopher Gibbs. “He was a lot girlier than she was, it has to be said. She wasn’t unwomanly, and he obviously adored her.”

As time went on, however, Kirsten found his attraction to other men progressively more distressing. Part of their bond was in drink: like him, Kirsten drank heavily. Her death, from a heart attack at the age of 44 in April 1984, sent Procktor into a spiral of anguish and guilt. His alcoholism took greater hold, and with it his behaviour became more self-sabotaging; in his later years he would, for instance, simply give paintings away to people expressing interest at private views, to the chagrin of his galleries. Many friends fell away, unable to cope. Procktor became acquainted with Princess Margaret early in his career; she occasionally visited him at home and always saw his exhibitions. Their friendship lasted into the 1990s, until she, too, decide to withdraw. To friends he called her “a fag hag” – she enjoyed the company of gay men – but it seems that he was genuinely fond of her. His friend the art dealer James Kirkman recalls: “He was very friendly with her, even when she was a worse boozer than him. But he wasn’t snobby at all, and he wasn’t a name-dropper. Nothing would have turned Patrick’s head; he wasn’t that type.”

Sixty years after his first London show, Patrick Procktor: Stages pays tribute to an artist long overdue a reappraisal. At the centre are several large canvases from the 1960s – a period of stylistic and technical development for Procktor – including some not seen publicly in decades. They include “The Beach: Figures in Red and Black” (1962); the strangely surreal, Francis Bacon influenced “Three Figures from Memory II” (1965); and “Shades” (1966), based on the interior of a Soho gay club. In a scene reminiscent of a stage-set, its assembled cast is formed of Procktor’s friends and one-time lovers, among them the filmmaker Derek Jarman and the artist Keith Milow. It celebrates the necessarily covert gay scene, in a period, when, as George Melly has written: “Soho at weekends was full of Mods pilled up to the eyebrows, dressed like kaleidoscopes, and bouncing in an out of the cellar clubs like yoyos.”

In recent years, propelled by retrospectives in the UK and Italy, Procktor’s stock has risen, his work newly appreciated by collectors and artists

“Shades” was among many queer-themed pictures in the artist’s third Redfern Gallery show; others depicted leathermen, like escapees from Tom of Finland’s drawings, and The Rolling Stones in drag. That show opened in May 1967, two months before the Sexual Offences Act became law, decriminalising private homosexual acts between consenting adults over the age of 21 in England and Wales.

Both Procktor and his gallery were doubtless aware of – and indeed welcomed – the controversy and publicity his subversive paintings were to generate: one reviewer described them as “markedly fetishistic and orgiastic in tone”. And in fact, the show led to a commission from the Royal Court Theatre, who asked him to draw a portrait of Joe Orton, for reproduction in the programme of a double bill of the playwright’s work staged that June. Now in the National Portrait Gallery, the ensuing drawing is a knowing collusion between artist and subject, in which Orton reclines on a divan, naked but for his socks.

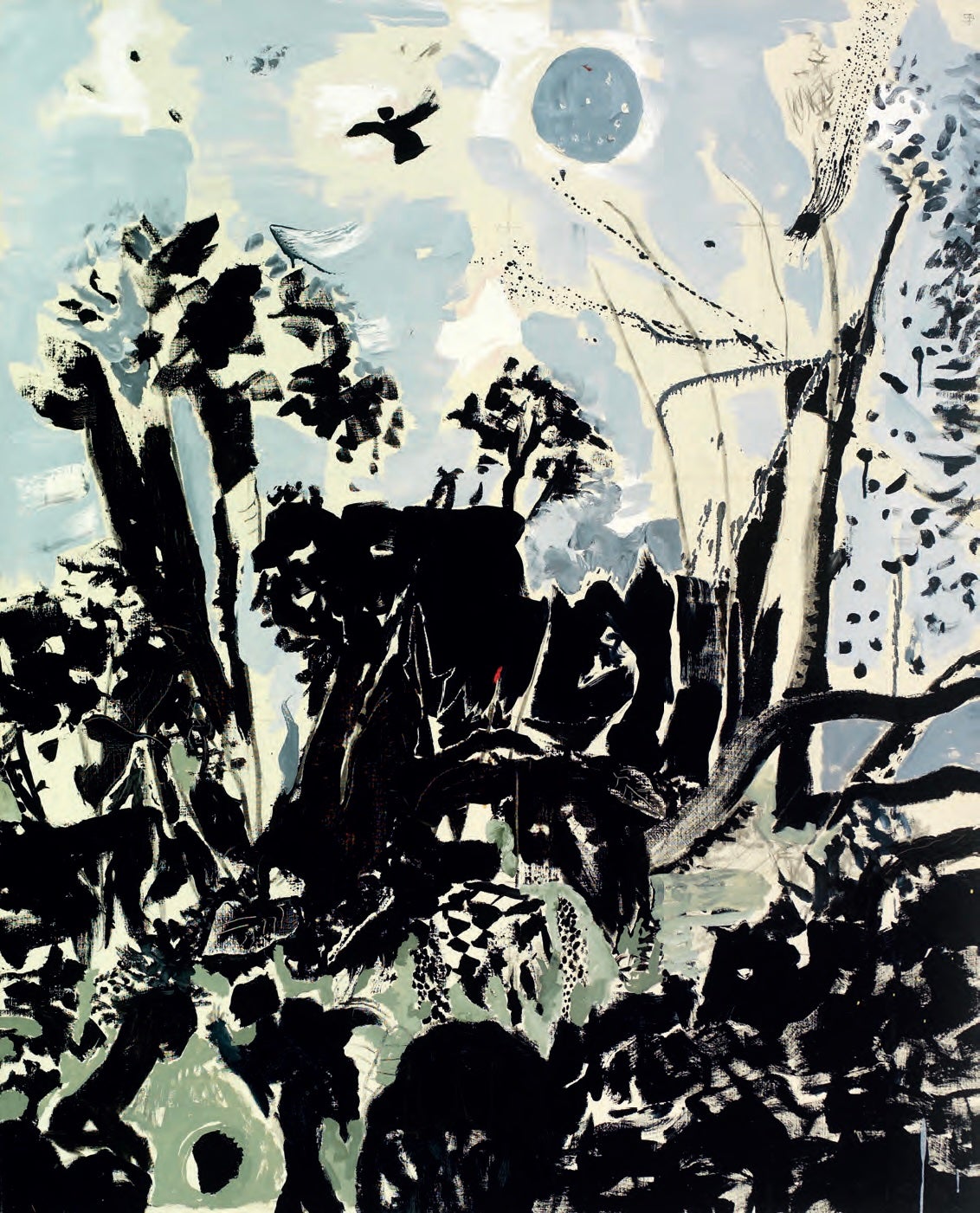

Towards the end of his life Procktor stayed for a time with family friends in Gloucestershire. There, marking something of a return to the expressionistic oils of his first show, he made his final works on canvas. They include an untitled nocturnal landscape of shadows, painted mostly in black, which reads as an elegiac swansong.

By the time of his death at the age of 67 in a London hospital in 2003, Procktor was largely forgotten. In recent years however, propelled by retrospectives in the UK and Italy, his stock has risen, his work newly appreciated by collectors and artists responsive to its understated painterly language, its colour and poetic distance. Among contemporary admirers are the artists Peter Doig, Kaye Donachie, Luke Edward Hall, and Alessandro Raho, and the fashion designers Erdem and Jonathan Anderson. His star is once more in the ascendant, and with this new show the dandy art twin has made his return.

Patrick Procktor: Stages, curated by Ian Massey, is on at The Redfern Gallery in London from 8 October to 8 November

A fully illustrated catalogue of the show is available, along with ‘Patrick Procktor: The Complete Prints’, a newly published catalogue raisonné of the artist’s work as a printmaker