Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Invitation-only private auctions, where select groups of billionaires are approached to bid for high-priced works, are becoming an attractive format for collectors who want to avoid the spotlight while disposing of artworks.

Private auctions have been an innovation of the past five years, say industry figures, as the public auction market has become a less profitable forum with a reduced pool of bidders, especially from Asia, for top works. Last month, a bust by Alberto Giacometti estimated to be valued at more than $70mn failed to sell at Sotheby’s.

The rise of the private auction was also driven by collectors’ post-Covid unwillingness to travel the world for public sales. One collector said: “Something happened with Covid — auctions never came back properly . . . [Previously] everyone wanted to see who was in the room.”

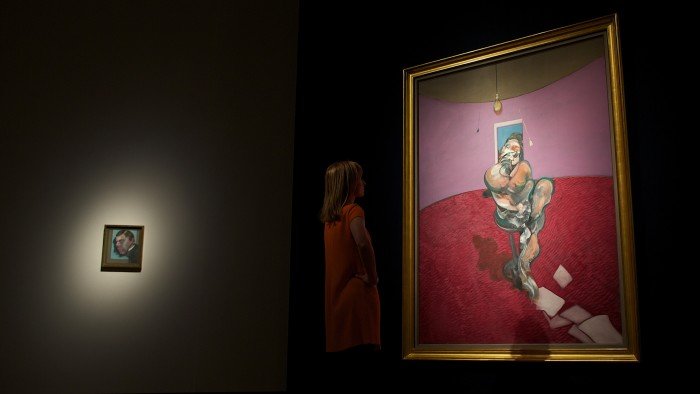

When artist and restaurateur Michael Chow wanted to sell Francis Bacon’s “Portrait of George Dyer Talking” (1966), he asked commercial gallery Lévy Gorvy Dayan to hold an invitation-only private auction. The sale last August, which took place in a specially mocked-up sale room in the gallery’s New York space, started at $50mn and the six telephone bidders included Israeli shipping magnate Eyal Ofer, according to people familiar with the sale.

Chow declined to comment. The identity of the seller and the name of the painting have not been previously reported. The painting last sold for £42.2mn (then $70.3mn) at Christie’s in 2014.

Auction sales fell 20 per cent to $23.4bn in 2024, the lowest level since 2020, according to the Art Basel/UBS Art Market Report 2025, “with double-digit declines in the value and volume of sales in the $10mn-plus segment”.

Private sales processes played on the psychology of collectors who desired exclusivity, said Brett Gorvy of Lévy Gorvy Dayan.

“Public auctions are a democratic process — if you can afford to buy you’ll be in the room — but in [the Bacon sale], you had to be invited to participate.” Collectors had to sign non-disclosure agreements.

Gorvy said the gallery had chosen a summer sale because “frankly it was when [the bidders] were on holiday on their boats, so there’s no other distraction than this major object”.

Last year, Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev sold Mark Rothko’s “No 6 (Violet, Green and Red)” to Ken Griffin of hedge fund Citadel for about $195mn in a private auction through Christie’s. The painting had been one work involved in Rybolovlev’s long-running legal dispute with his former art adviser Yves Bouvier over allegations of overcharging (which Bouvier denied).

Jeremy Hodkin, who first reported the Rothko sale in his Canvas art-market newsletter, said private auctions were a tactic only for the few: “This type of format isn’t for selling a $10mn Warhol, it’s for selling a $100mn Warhol.”

The desire for privacy can be motivated by the embarrassment of financial need, wanting to be rid of a contested work or simply discretion. Auction houses and galleries have long offered private sales, but the competitive auction element is new.

As the attraction of private auctions has increased, organisers have explored different ways of holding them. In some instances, bidders are invited to see the work of art, typically in a warehouse or art-storage facility, and are then given a window in which to bid, according to a wealth manager who has collector clients.

Loïc Gouzer, who founded Fair Warning, an auction app for approved bidders, said private auctions offered “confidentiality combined with competitive bidding”. He said Fair Warning was developing technology so it could hold what he called “dark auctions” for invited bidders only.