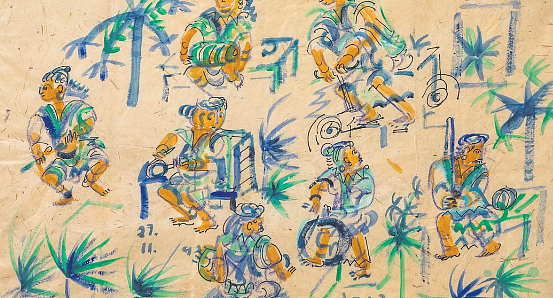

Untitled watercolour on paper

There are times when the pages of history are turned again and gems that have been hiding in plain sight are discovered. Sculptor Leela Mukherjee is one such gem. The artist, who practiced from the 1940s to the end of the century, forges an individual expression that merges together the classical, modern, and folk, besides Indic, Western and African streams. Her ongoing exhibition—Leela Mukherjee: A Guileless Modernist—at the Vadehra Art Gallery in Delhi has on show a collection of sculptures along with drawings, etchings and lithographs, curated by art historian R Siva Kumar. It is the most comprehensive presentation of her work to date.

A science graduate, Mukherjee in 1937 decided to study art at Santiniketan, where she came across renowned sculptor Ramkinkar Baij. While many believe that she was inspired by the master, Kumar thinks otherwise: “Although both were sculptors, Baij was primarily a modeller and Mukherjee a carver. So, it is unclear if she learned the craft of carving from him. But Mukherjee shared his spirit of independence and self-belief and remained a life-long admirer.”

According to Baij, Nepali carver Kulasundar Shilakarmi was an early influence on Mukherjee. “A few of her early works show marks of her apprenticeship under him. However, she outgrew his influence very soon,” says Kumar, who worked on the exhibition along with the Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.

The aim was to create awareness about Leela Mukherjee’s works, who had remained away from the limelight that shown bright on her husband Benodebehari (though posthumously)—a fellow student at Santiniketan—and daughter Meera, who has been internationally acclaimed for her hemp sculptures. “Although archival documentation started in 2019, due to the pandemic, we could not begin work in earnest until 2022. And it took almost two years to put the exhibition together,” he says.

Like most modern artists, including Benodebehari and Baij, she turned away from the classical and post-Renaissance realist traditions and sought inspiration from a host of pre-classical, medieval and ‘primitive’ arts. She found robustness, earthiness, and greater expressive possibilities in these traditions, which the rarefied classical arts lacked. “But unlike her husband Baij, her talent was largely hidden from the world. The reason could be her indifference to fame and commercial success. Also, although she was a dedicated artist for over 20 years, she worked as an art teacher at the Welham Boy’s School in Dehradun and teaching in a school is unlike teaching in an art school where one’s work as an artist and teaching is more closely interconnected. Finally, though she periodically exhibited her works, she worked and lived in Dehradun and escaped the attention of connoisseurs and critics who are concentrated in metropolitan cities,” says Kumar.

In her later years—she died in 2003 at the age of 86—Mukherjee turned to modelling in wax and etching and spent most of her last years painting and drawing, which by comparison is less arduous than carving. “She undoubtedly belonged to the first generation of modern women sculptors in India and is in that sense a forgotten pioneer who kept the spark alive through sheer perseverance. The exhibition aims to bring her work back into focus and claim a place for her in the modernist and feminist discourse in art,” says Kumar.