About six years ago, Alissa Bennett, a director at the Gladstone Gallery, fell under the thrall of Donna Tartt’s 1992 novel, The Secret History. The book traces a coterie of students studying ancient Greek at an isolated Northeastern college. Myth, reality, and ritual overlap and ultimately Dionysian rites collide with deadly hubris. Bennett read it, and upon finishing, reread it. For the next three years, she listened to the audiobook nightly.

Bennett has now assembled a group art exhibition based on the novel. “The Secret History” runs through August 2 at Gladstone 64. It’s a mélange of artworks both sourced by Bennett and many she commissioned. She bought 12 copies of the novel and doled them out to some of her favorite artists with the assignment: “No rules. Make whatever you want.”

Installation view, “The Secret History, organized by Alissa Bennett,” Gladstone Gallery, 2024. Photo: Daniel Greer, courtesy of Gladstone Gallery.

Last week, Bennett, looking smart in oversized Levi’s, a tucked-in white blouse, and an enormous statement gold chain, was walking me through the exhibition. She explained that she didn’t reach out to the author, Donna Tartt, “because I like her too much. The whole point of the mystery room in these ancient Greco-Roman cultures was not to worship the idol, but to encounter the idol, right? I don’t want to meet her.”

The artists featured range from more familiar names, like Hope Atherton and Matthew Barney, to her astrologer Micki Pellerano. “It’s a conjuring of some god or another,” Bennett said, motioning to his intricate depiction of a deer-horned deity coalescing. “He goes into these trances and makes these incredible drawings. If you go to his home, they’re all over the walls.”

The writer and Gladstone Gallery director Alissa Bennett. Photo: Leigh Ledare.

Since its release, The Secret History has sold over 5 million copies. “What’s so spectacular about it is that everybody likes it,” Bennett said as she ascended the stairs in the gallery, a converted Upper East Side townhouse. “But there’s something subtextual that’s not just this mystery told in reverse.” The inverted intellectual crime drama follows a descent into darkness with a group of super-privileged Classics students at a college; it is loosely inspired by Bennington College, where both Tartt and Bret Easton Ellis studied.

“Something else makes it almost universally appealing,” Bennett continued. “What does it mean to be young at this specific time in American history? What does it say about this idea of time in terms of this valorized past and the limitless future? The present is this horrible and interminable sort of liminal space, this waiting room where you don’t try to enact anything because you’re either dreaming or longing. That’s what the book became for me after reading it twice and listening to it for 900 days. It was less about plot and more about the subterranean current that runs underneath.”

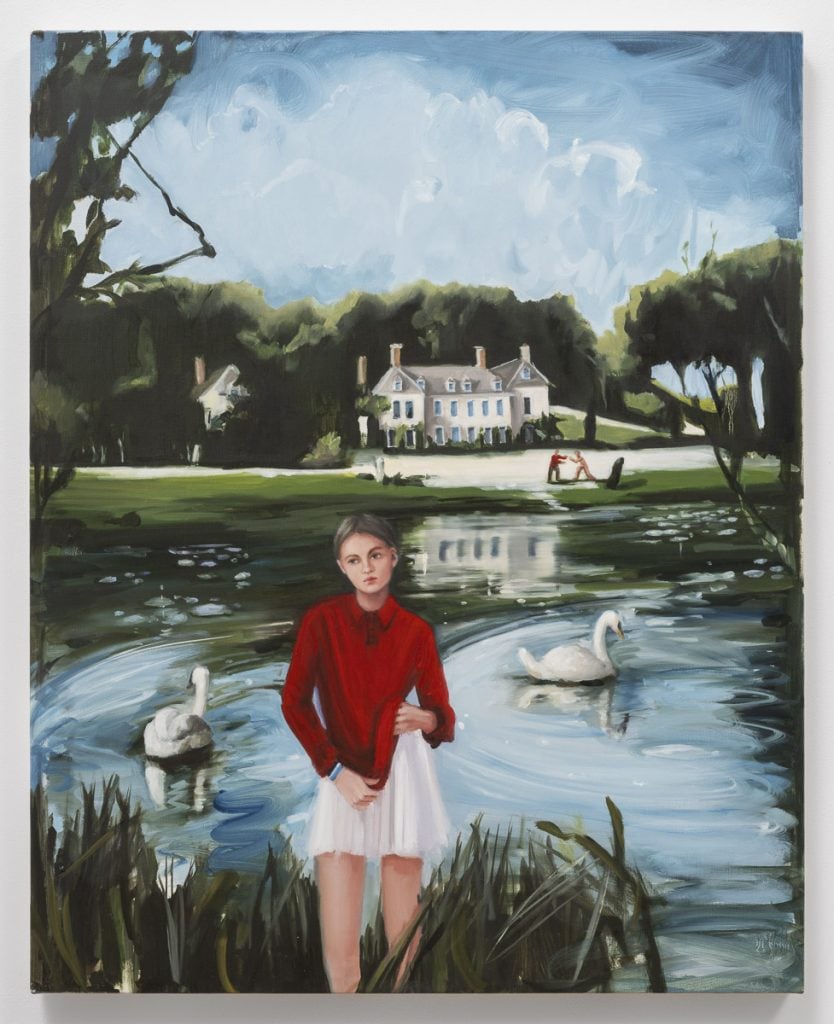

Karyn Lyons, The Duel, (2024) © Karyn Lyons Photo: Anthony Flores, Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

Barbara’s Legacy

Her debut exhibition has garnered much-deserved buzz, and Bennett is inspired to revisit curation in the future. “I think it’s interesting for people to encounter a show that’s narrativized,” she said. “For people that are familiar with the book, they can go in and catch the beat. For people that aren’t, I hope that they read it because people should read more.”

The roundabout origins of the show began with a conversation Bennett had with the gallery’s founder, her mentor the art world legend Barbara Gladstone, who passed away last month at 89, four days before the show opened. “I’m not a curator,” Bennett said. “Probably my filthy secret is that I don’t really care about how things look—like at all. I wasn’t going to Barbara and saying, ‘please, please, please.’”

Bennett is prone to wry soliloquy with tangents expanding like tentacles. Her self-edit button is charmingly, permanently malfunctioning. “My kid loves classical music and Barbara was a big supporter of classical music,” she explained. “Last summer, my son and I went to see her at her country house and we had dinner with Itzhak Perlman, the guy who popularized that Paganini song “23 Caprices” or something.” And she said to him, ‘This is Alissa, she works with me and she does a very convincing job of performing as though art is the thing that she cares most about in the world. But really what she cares about is literature.’ I thought about that a lot and thought, ‘what an incredible opportunity!”

Matthew Barney, ENVELOPA: Drawing Restraint 7 (manual) C (1993). © Matthew Barney. Photo: Anthony Flores, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

Bennett paused before wistfully continuing. “You hustle and hopefully you find someone who’s like, ‘I know you’re hustling,’” she said. “The vision becomes different when you don’t care about how things look, but you care about narrative. It physically coalesces in a different way. I thought, ‘This is a chance to celebrate what Barbara understands about me and do a literary show about a book that everybody loves. My impulse would be different—I’m an Edith Wharton fanatic—but nobody wants to come to a show about The Custom of the Country. They want to see something that has a little sex in it.”

“The Secret History” is Bennett’s first outing as a curator at Gladstone (she’s been at the gallery since 2018). A “director” role is something different depending on the gallery, and Bennett’s job mostly entails writing and working closely with artists. By design, each director brings something different to the table and this new career segue might have been part of Barbara Gladstone’s grand plan for her all along.

“Some directors are incredible at sales. Some are very good with museums, some are very good with artists,” Bennett said. “Everyone has their area of specialty. We all know that none of us are Barbara because she was so dynamic, but she very carefully assembled a staff of people where everyone has some kind of facet that reflects one part of her. Collectively and cumulatively we can kind of approximate what she did. That was a visionary way of constructing her business. It’s like we’re cyborg Barbara. We all have a part of her and everyone was hired for whatever that thing is.”

Installation view, “The Secret History, organized by Alissa Bennett,” Gladstone Gallery, 2024. Photo: Daniel Greer, courtesy of Gladstone Gallery.

We walk in front of Matthew Barney’s ominous ivory satyrs. “This is from Drawing Restraint 7,” Bennett said. “I really wanted to show the video, but didn’t have the budget to install it, so we settled for the stills. And he’s having a moment with 800 shows!” Among them, the “Cremaster Cycle” films just screened in L.A. and “Secondary” is currently in Gladstone’s Chelsea outpost. At Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain in Paris is a major exhibition, with rollouts in other galleries in Paris, L.A., and London as well.

Bennett then walks up to Kayode Ojo’s bodiless sculpture, a spectral wig paired with a sequined dress based on one of the book’s secondary characters. “This is Francis’s mother Olivia!” Bennett said about the piece. Nearby, painter Karyn Lyons depicted a pensive, patrician girl in a red blouse; behind her is a lake of swans and what could possibly be blurred fisticuffs in the background.

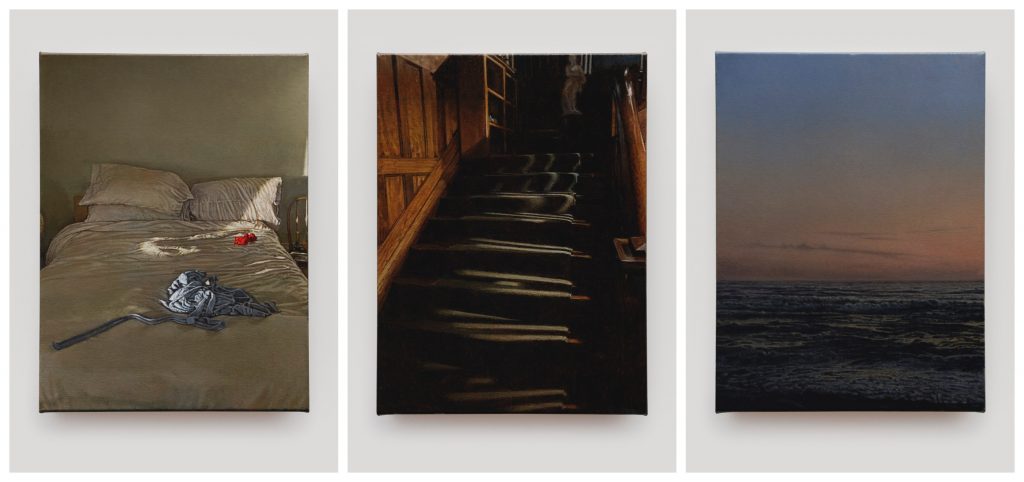

Nicholas Bierk, Bed (2024), Staircase (2024), and The Night Dances (2024). © Nicholas Bierk. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery

“As a mature woman, I can’t necessarily touch it directly anymore,” Bennett said. “But Karyn reminds me of what it’s like to be of a certain age. She’s not 20 either, but she has it at her fingertips somehow.” This painting brought to mind the character Camilla, an icy and enigmatic twin from The Secret History.

The Japanese-Mongolian painter Arisa Yoshioka had never read a novel in English before Bennett handed her Tartt’s book, which clocks in at over 600 pages. “She was like, ‘I don’t know if I can do this, but I’m going to try.’ Three weeks or so later I get an email that has snapshots of her annotated copy. And she was like, ‘I understood it.’ It was a really thrilling, breakthrough moment for her, which I think comes through in this [work]. This painting is drawn directly from the story. It’s the scene where Charles shatters a mirror above a mantle.”

The novel has been optioned various times, but it has yet to have an official screen version, but there is an obscure 2006 video art adaption. Two days before the show opened, the artist Matt Connors alerted Bennett to this lo-fi gem. Faustus’s Children by Michelle O’Mara plays on a television atop a plinth. “They did the conjuring scene and made a paper forest!” Bennet said. “It’s Kenneth Anger with glitter falling from the sky—super low budget, but really incredible. It was very last minute, but it’s one of my favorite things in the show. It’s the most direct reference.”

Adam Putnam, Untitled (2018). Photo: Daniel Greer. © Adam Putnam Photo: Daniel Greer, courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

Adam Putnam’s striated abstract gold leaf piece is beautiful and haunting. “He’s one of my favorite artists,” Bennett said. “He makes these drawings or sculptures of ruins, but they’re kind of self-portraits.He does a lot of performance art and will install an obelisk in the middle of a gallery. Decay is always ricocheting around in there.” The artist also supplied a creepy sculpture that is a long branch that extends from the wall and ends in a carved fingertip. “So simple, so terrifying, perfection,” Bennett said. “Because we want to be a little scared, right?”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook: