A few months back, when high-profile gallery closures were making headlines and the commercial art world was considering what a new-era gallery model might look like, dealer Hal Bromm was putting the finishing touches on his namesake gallery’s 50th-anniversary exhibition. Five decades is a remarkable lifespan for any gallery, but it is even more impressive when you consider that Hal Bromm Gallery was the first contemporary art space to open in what would become Tribeca. The exhibition “50: The View from Tribeca,” which runs through November 29, 2025, builds on the gallery’s previous anniversary exhibitions (“TEN,” “20,” “30,” “40”) with works by key artists from the gallery’s half-century.

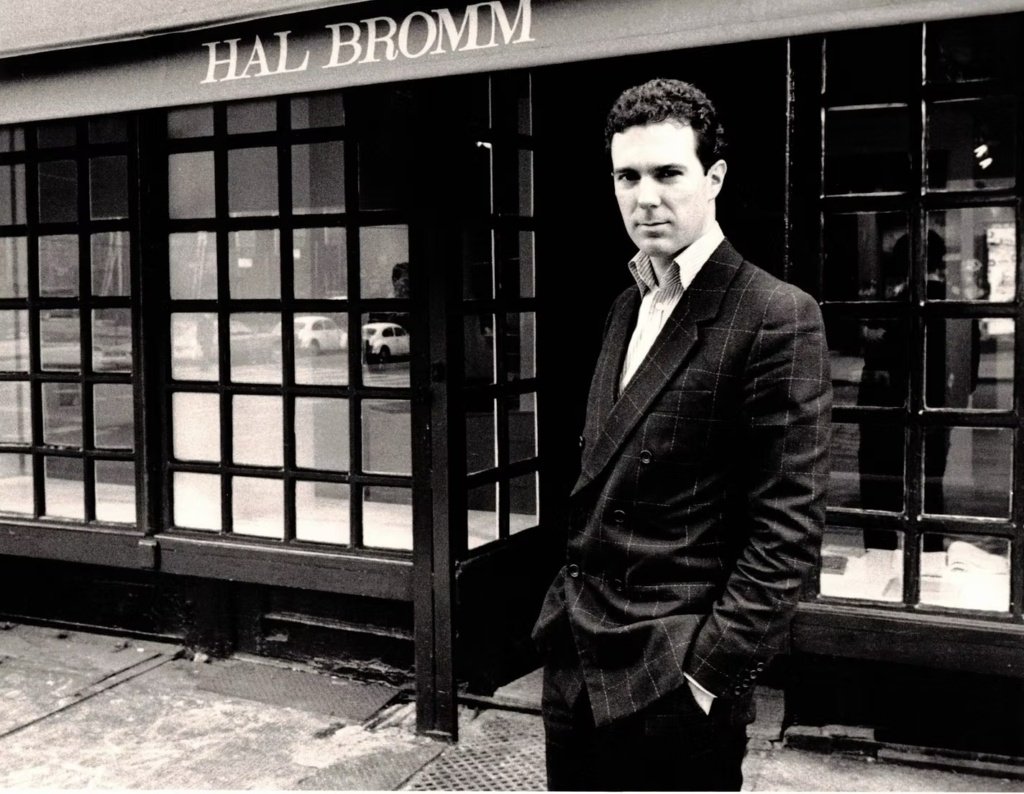

Behind the gallery’s lengthy run is Bromm, a defining presence in both contemporary art and the neighborhood where he mounted shows of work by quintessential New York artists such as John Chamberlain, Rosemarie Castoro, David Wojnarowicz, Kiki Smith, Martin Wong and Donald Judd. Luis Frangella and Keith Haring had their first solo shows at Hal Bromm Gallery, which developed a reputation for supporting emergent and experimental talent, showing work by artists like Jeff Wall, Robert Longo and David Salle early in their careers. Looking beyond the downtown avant-garde, Bromm organized international exchanges, bringing work by Italian artists such as Alighiero Boetti, Paolo Icaro, Mario Merz, Giulio Paolini and Michele Zaza to New York and introducing U.S. artists to Italy.

In NEW ART, OLD BUILDINGS: STORIES FROM HAL BROMM’S TRIBECA, originally conceived by former directors Logan Payne and Katie Svensson and published to mark the gallery’s golden anniversary, painter Lucio Pozzi says, “I never consider [Bromm] a gallerist but a collaborator integral to thinking and doing the art.” And he’s not the only one. Flip through and there’s Robert Yasuda calling the gallery a “sustaining presence” and Gracie Mansion calling Bromm one of the “most loyal dealers.” There’s a distinct throughline across pages: Bromm’s commitment to collaboration, his discerning eye, his willingness to experiment and his overall thoughtfulness. Sur Rodney sums it up tidily when he writes, “Hal has always stayed committed to the artists he continues to admire, and that is why he is so loved.”

Hal Bromm Gallery is something of a rarity in the art world—visionary yet humble, relatively modest in scale while being outsized in its influence and looked on with affection by those in its orbit. Much, it would seem, like the man himself. I couldn’t make it to the opening of “50: The View from Tribeca,” but I was able to connect with Bromm to ask him what it is about his approach that has allowed his gallery to outlast so many others. His answers to my questions reflect both the attentiveness and the graciousness for which he is known.

You’ve been in Tribeca for a long time. What did ‘Contemporary’ mean on day one, in pre-brand Tribeca? How has it changed?

In reflection, ‘Contemporary’ in 1975 seemed more adventurous. Opening our first show on Beach Street was not predicated on how well it would sell, but rather focused on sharing unknown work from London with a new audience. Beach Street was an outpost in an area few people knew, so coming that far downtown was an adventure, a mark of someone who was a true art aficionado. The galleries that followed ours were well outside the mainstream, breaking new ground by showing relative unknowns. Today’s influx of galleries to Tribeca is rewarding, and among those new to the area are spaces that focus on new art. Along with that is also a focus on historically unappreciated artists, so the word ‘Contemporary’ in 2025 has a new meaning.

Do you feel that your gallery played a role in shaping the neighborhood’s cultural identity as it exists now?

Hal Bromm Gallery in the ‘70s was a pioneer space that helped introduce a new neighborhood to collectors both outside the city and above 14th Street. Opening a space in an unknown area made the gallery a destination, perhaps even a novelty, and with time, public familiarity with the area grew. As an early homesteader in what became Tribeca, I was something of a PR guy promoting the area, and by the mid-1980s became involved in the effort to protect the historic character of the mercantile buildings that make up much of the neighborhood. After Edward Albee, Bob DeNiro and Jim Rosenquist agreed to sign on to a “Dear Neighbor” letter urging residents to join the preservation effort, things really took off. The media attention helped push the Landmarks Commission to act, ultimately protecting four small historic districts within Tribeca by 1991. That in turn drew more interest from potential residents who relished the idea of living in a converted loft building that would not be subject to unsympathetic change. The 50th-anniversary book we just published, NEW ART, OLD BUILDINGS: STORIES FROM HAL BROMM’S TRIBECA, explores this history in depth.

Fifty years is a long time. How have you seen collector priorities change over five decades? What’s changed about discovery?

In the early decades, it was rewarding to work with collectors who bought work they enjoyed, unconcerned by what others might think of their choices. Many younger collectors we work with today share that sensibility, but there are some whose focus seems to be more on what they should buy, as opposed to buying what they like. Looking back, I remember Milton Brutten, based in Philadelphia, who engaged with artists and became deeply involved in works by those he collected. His collection was utterly personal. Elaine Dannheisser was another independent thinker. She joked that her circle of friends included collectors who would check in with frequent phone calls to learn what new artists she had discovered, often following her lead. Perhaps today there is too much concern for a young artist’s track record, level of exposure and media attention. Social media can detract from seriously considering an artwork and lead to instant decisions that can be misguided.

Edward Albee was a collector who looked at art carefully, believing that revisiting art in any form (a film, play, opera, sculpture, painting, etc.) was important to understanding it. I’m not sure many people follow that advice today, but it is good practice.

Among the decade-marker shows—“TEN,” “20,” “30,” “40”—and now “50: The View from Tribeca,” are there curatorial throughlines that tie the five anniversary chapters together beyond the gallery’s longevity?

With each anniversary, it felt important to look back at the previous ten years and draw from the works and exhibitions. Yet looking back, the curatorial lines really changed with each decade. At “TEN,” we were young enough to have only a few years to ponder, but by “30” so much had shifted, both culturally and socially. AIDS had taken a horrendous toll in the art world, and we decided to dedicate the 30th Anniversary to the lives of four artists whose works we had championed early on: Carlos Alfonzo, the Cuban artist who had come to Florida as part of the Mariel Boatlift; Luis Frangella from Argentina, who had come to the U.S. to study at MIT and then landed in NYC by the early ‘80s; Keith Haring, the SVA student of Lucio Pozzi who sought approval to forego a degree as his irrepressible talent was bursting forth; and David Wojnarowicz, whose cruel childhood led him to flee his home for the streets of New York. For the “40” show, we included works by virtually every artist who had ever been shown at the gallery, a monumental task but richly rewarding. “50” presents a more focused view, highlighting works by both well-known and younger artists.

What are you most excited about with regard to this particular decade-marker exhibition?

Much of the excitement for the 50th Anniversary has been the relationship between the exhibition and the book that accompanies it. “The View From Tribeca” exhibition relates directly to the stories in NEW ART, OLD BUILDINGS. The book was the brainchild of early gallery director Logan Payne, who in her years with the gallery designed and edited the MOVING 1977 catalogue, the “TEN” catalogue, and more. Logan and her co-editor Katie Svensson have produced a wonderful collection of stories from artists, collectors, critics, curators and gallery friends that chronicle the gallery’s 50-year history through the personal lens of each contributor. While I was drawn into the book to help with some of the actual history, it is really the story of the many wonderful people in the Hal Bromm Gallery ‘family.’

If you could restage any exhibition from the gallery’s 50 years, exactly as it hung, which would it be?

Tough question. Our Rosemarie Castoro memorial exhibition, “Rosemarie Castoro: 1939 – 2015,” celebrated the career of a major artist whose death ended a career that extended back to the 1960s. Castoro’s early Prismacolor Pencil Paintings were first shown at our Ten Beach Street loft. Rosemarie was a personal friend, and curating an exhibition honoring her life was not easy, but the exhibition won kudos. We included a panel discussion with Barbara Rose and Alexandra Anderson, two critics who had early on promoted her work. Castoro established herself in the late ‘60s as one of the few well-recognized female painters among the New York Minimalists. The retrospective exhibition celebrated the uphill climb that Castoro’s friends and peers, including Eva Hesse, Ree Morton and Hannah Wilke, faced. Like them, Castoro was often overshadowed by men, including her then-husband Carl Andre and their friends Sol LeWitt, Frank Stella, Mark di Suvero and Robert Smithson. As that shifted in recent decades, the pioneering work of Rosemarie and other women of her generation has received well-deserved attention.

For reasons already mentioned, our 30th-anniversary exhibition would be another I’d happily repeat, honoring dear friends whose lives and careers were cut short by AIDS.

Our 1978 exhibition honoring the life of Andre Cadere is another. A solo show of new works, long planned with Andre, was abruptly ended by his sudden death only months before. Rather than cancel, we borrowed works from collectors to hold a memorial exhibition in his honor. It was a beautiful tribute, but of course, nothing was for sale.

Lest you assume that I only have a fondness for tributes, I’d also be glad to restage our first solo shows with Keith Haring, Luis Frangella, David Wojnarowicz, the Russian painter Natalya Nesterova and, most recently, Joey Tepedino.

You’ve weathered a lot of storms (9/11, the 2008 financial crisis, the pandemic, etc.) and come out ahead. What’s your secret of survival?

Perhaps the answer is optimism. Generally, I look for the good in people and the positive in bad situations, keeping faith there is always a blue sky ahead. You don’t mention the 1987 Stock Market Crash, but that was fairly traumatic for many East Village colleagues, young dealers who had by then established themselves but perhaps become a bit overleveraged. Seeing so many talented people give up was tough. 9/11 was horrible on every level, and the sense of being close to an unfolding tragedy (the gallery is just a few blocks from the WTC), yet powerless to assist, was unbearable. While it was clear that life above 14th Street was relatively normal, downtown was at first unreachable, and the gallery closed. Camping out in a hotel was no fun, and trying to function outside the office was nearly impossible. After a forever few weeks, friends were coming downtown to the gallery, uplifting our morale, taking us to dinner. The love we’ve felt today, celebrating the 50th Anniversary, reminds me of that time. Those relationships are the essence of a good life.

The pandemic was different: everyone was affected. Online became our lifeline with the gallery space shut down. While I still relish sharing art in person in the gallery space, the reality is that many collectors are now comfortable viewing art remotely.

We’ve seen a recent wave of closures and ‘sunsets’ from respected, well-established galleries (from Marlborough to Kasmin’s transition and other high-profile exits). What do you see as the keys to avoiding burnout in an ever-more-frenetic art market?

Maybe the best answer is to not over-expand? Perhaps closures are not so much due to burnout as to other factors. Every closure is different, unique to gallery owners and their circumstances. Knoedler was perhaps the most infamous case, with clear fault lines in play.

I remember deciding to head off my own burnout by getting back to only one New York City location. When we opened the East Village gallery, it was exciting and stimulating, but several years later, it was clear that managing two spaces, two sets of staff and all that entailed was pulling me further from engaging with art and artists. I value contact with not only artists but what I call the gallery family: critics, writers, curators, collectors. The weight of bureaucracy began to impinge on those connections. When we eventually closed Avenue A at the end of the ‘80s I missed the great space we had and the vibe of the neighborhood, but it was a pleasure to be free of so much busywork.

Not to be morbid, but what does succession look like for an independent gallery with a 50-year identity—continuity through team, foundation or a defined wind-down plan?

The gallery team is quite young and full of enthusiasm and energy. I hope that the gallery will continue to thrive through their good work, even if I begin to step back. While there are no plans for that, one must face the unpredictability of life. And as my friend Marcia Tucker once told Lisa Phillips (now retiring as director of the New Museum), don’t die behind your desk.

What is perhaps another question related to the life of a gallery is whether galleries as physical spaces will ever regain the appeal and importance to collectors they once had. Back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, visiting galleries was a regular pastime for many people, even if they were only window shopping. Out-of-state and international visitors called ahead to plan time together, and lunches and dinners during their visits were a particularly beautiful way to stay in touch and share new works. There does seem to be a cultural shift toward art fairs replacing the gallery experience. While we have exhibited in fairs around the world, including Basel, Zurich, Chicago, Bologna and other venues, it was at a time when fairs played a very different role.

Today, for some collectors, gallery visits seem like a rarity. There are dealers who no longer have a gallery space, maintaining only an office to support fair attendance. Others have entire staffs dedicated to perpetually preparing for their next fairs, which seem to come with increasing frequency. Observer lists over 160 fairs worldwide this year. In December, fourteen fairs will come and go during Miami Art Week. In New York, more than twelve fairs are scheduled for next spring. While the 37th edition of the October ADAA flagship art fair has been canceled, it is clear that the public supports attending art fairs, even though, unlike galleries, they must pay for the privilege. I recall Roberta Smith’s reminder to the public on the rich variety of art available in the city’s many galleries, all on view for free.

What advice would you give a young gallerist hoping for career longevity?

I will never forget Paula Cooper’s advice to me when she heard I was opening a gallery: don’t expect to make any money. How true that was at the beginning, but fortunately, things picked up quickly. To young dealers now, I’d say let passion lead you to a carefully considered business plan. If you believe in the work of the artists you exhibit, always invest in their work. Norman Braman, the Miami-based art collector, once responded to a question about art advisers. He replied that gallery owners who invested their own money in the art they exhibited were the best art advisers. As a dealer, your commitment to your artists is important when you are promoting their work to your clients.

More Arts interviews