Emily Hass, drawing from “Water Shapes” series. In “The Numbers Game” at University of New England campus in Portland. Image courtesy of the artist

You may have graduated years ago, but learning is never complete. This fall, the state’s colleges and universities are offering a bevy of shows that allow you to play art student again, albeit without a focus on a degree. All the exhibitions here take us “back to school,” teaching us something new, interesting or surprising about a particular artist, aesthetic movement or form of painting, sculpture, printmaking or other media.

Bates College Museum of Art

75 Russell St., Lewiston, 207-786-6158, bates.edu/museum

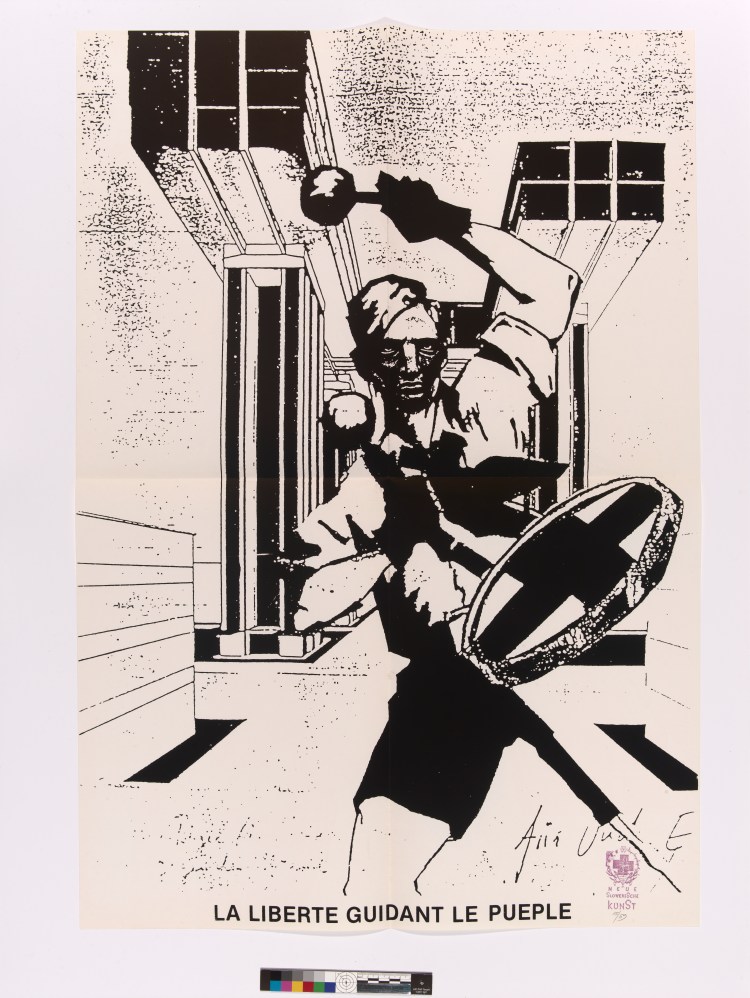

“Neue Slowenische Kunst | Monumental Spectacular” (or NSK, through Oct. 5) is an intriguing show that looks at the work of an organization of creatives that came together in 1984, a conflictual time when Slovenia was caught in a collective post-Tito vise grip of competing nationalist, capitalist and communist ideologies. It is a sleeper, and worth seeing before the Bates fall shows open Oct. 24.

NSK, says exhibition curator Samantha Sigmon, “used conceptual, experimental and collaborative art to question all power regimes – be they communist, capitalist, etc., and obscured any strong endorsement or disavowal of any one thing or another. They didn’t do this through fear, but just as artists working on a project adjacent to, but not about, politics.”

Laibach Kunst, “La Liberté Guidant le Peuple (Liberty Leading the People),” 1985, lithograph on paper 32 3/4 x 22 3/4 inches, Bates College Museum of Art purchase with Elizabeth Gregory MD ’38 Fund, Dorothy Stiles Blankfort Fund, and Dr. Robert A. and Minna F. Johnson ’36 Art Acquisition Fund, 2015.20.4. In “Neue Slowenische Kunst | Monumental Spectacular” at Bates. Courtesy of Bates College Museum of Art

Audiences, she feels, “can learn a different mode of making collectively, but also of addressing political issues through a melded artistic, historical and conceptual lens. And guests also learn a bit about the history of European and Eastern European avant-garde and of communist regimes in central and eastern Europe.”

“Across Common Grounds: Contemporary Arts Outside the Center” (Oct. 24 through March 15) “draws upon diverse styles and media from traditional craftwork to digital art,” Sigmon explains, “featuring works by approximately 20 artists living across America that expand, deepen and challenge how we cultivate and connect to land, culture, art and one another in rural places.” As her first organized exhibition, she says, “I hope it will tease out and update many definitions of the rural, show how layered these artists’ experiences and works are, and question what the centers of the art world are today, as well as what art exists within or without these centers.”

“ARRAY: Recent Acquisition Series” is a rotating exhibit presented in three segments. The first (featuring a textile by Jeffrey Gibson and a woodblock by Sarah Rowe – both Native American artists) runs from Oct. 24 to Mar. 15. A second opens in January and a third in February.

Bowdoin College Museum of Art

245 Maine St., Brunswick, 207-725-3275, bowdoin.edu/art-museum

“In the Fullness of Time” (through Nov. 10) is a solo show of mostly large-scale artworks by Abigail DeVille, a 42-year-old Black artist from New York whose recent tenure as artist in residence at the school (2022-’23) provided a springboard for developing this body of work. A breathtaking array of found materials conspires to prod discussions of resilience despite forces – racism, displacement, migration, violence, poverty – that continue to impact the Black American narrative.

“I am struck by the plethora of pieces that incorporate material evidence of both building and deconstruction,” observes Anne Collins Goodyear, who with her husband, Frank H. Goodyear, are co-directors of the museum. DeVille harnesses mirrors, doors, ladders, window frames, old shoes and more to question the foundations on which certain forms of art are valued and others ignored.

Some of DeVille’s references are to her African ancestry. For example, explains Anne Collins Goodyear, “the presence of diamond shapes in the works points to the visual rhetoric of the Eye of God present in African American yard work, a visual idiom with Central African origins, while glass bottles reference bottle trees with apotropaic qualities that have similar historical roots. What role do these traditions of African descent play in informing knowledge in the United States, and what of their intervention into European structures of understanding?”

Abigail DeVille, “Dark Matter, No Matter,” 2020, shopping cart, dolly, rope, bungee cords, zip ties, aluminum foil, costume jewelry, glass TV monitor, antique glass bottles, dinner bell, record rack, deflated inner tubes, 1950s metal child space helmet, painted plastic helmet, light bulbs, mirror shards, deconstructed mannequin, child’s mannequin head, 77 ¼ x 64 x 34 inches, Courtesy of the artist and The Bronx Museum, Installation view of Bronx Heavens at The Bronx Museum. Appearing in “In the Fullness of Time” at Bowdoin. Photo by Argenis Apolinario

DeVille also interrogates Bowdoin’s own role in creating this understanding. In “Miser’s Heart (yo so oro),” for instance, she incorporates a scaffold found on campus, a metaphor for the 18th- and 19th-century Eurocentric and Euro-American frames of intellectual knowledge that centered those cultures at the expense of others, leading collectors like James Bowdoin III to amass art based on those exclusionary principles.

“In her use of unconventional materials assembled to create new sculptural forms and her embrace of voices and narratives historically silenced and found at the margins of society,” adds Frank Goodyear, “DeVille demonstrates the power of creative expression to change how we see the world around us and to encourage new conversations about important issues of our moment.” Or, as his co-director puts it, the exhibition “is an invitation to all visitors to consider and to reconsider their own relationship to the physical and metaphysical forces that shape them, and a prompt to contemplate that which might be dismantled as we reconsider the futures we wish to erect for ourselves and for future generations.”

Some works are polemical. “Dark Matter, No Matter” is based on the spoken word poem “Whitey on the Moon,” where author Gil Scott-Heron narrated the economic struggles of two Black siblings against the backdrop of the Apollo moon landing. But DeVille takes it further by alluding to the pursuit of space exploration by uber-wealthy white men (hello, Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos), while underserved communities struggle for basic daily sustenance.

Colby Museum of Art

5600 Mayflower Hill, Waterville, 207-859-5600, museum-exhibitions.colby.edu

There’s so much going on at Colby this fall. But some notable examples are “Eastman Johnson and Maine” (which opened in June and runs through Dec. 8), a reinstallation of the Lunder Wing with a show called “Some American Stories” (opening Sept. 26) and “Surface Tension: Etchings from the Collection” (through Jan. 12).

“Some American Stories” continues what Lunder Curator of American Art Sarah Humphreville calls Colby’s “interrogation of what American art is. This idea of a multiplicity of stories seemed what we should be doing.” So, one wall in the Lunder galleries will examine American commerce as exemplified by trade among Native Americans, between white settlers and American Indians, and “mercantilism and its relation to colonization.”

Norman Lewis, “Untitled,” 1961. Oil on paper, 26 × 40 inches. The Lunder Collection. In “Some American Stories” at Colby. Photo courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery

“Surface Tension,” aside from being a beautiful show, is a fascinating tutorial on the various ways etching (with mordants, acids and metal plates) has been employed by many artists, including Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, John Marin, Leonardo Drew, Nancy Graves, Terry Winters and others. The infinite variety of visual and textural effects achieved by their experimentations and innovations is spellbinding.

Humphreville turns a spotlight on Eastman Johnson, a Maine-born 19th-century painter rarely mentioned these days whose work might initially feel a bit arcane. However, Humphreville’s recasting of his work is thoroughly illuminating. Consider, Humphreville says, that all the exhibition’s paintings were made between the leadup to and during the Civil War, as well as its aftermath. In this light, a work like “The Party in the Maple Sugar Camp” becomes notable for its absence of enslaved Black people, as it was a crop not dependent on slave labor. Or look carefully at “Barn Interior at Corn Husking Time,” where you can discern graffiti promoting Abraham Lincoln and his vice president Hannibal Hamlin. “He was painting at a moment when this country was feeling very pressured,” she observes of Johnson, “and we are also in a very fractured place now as a nation.”

Institute of Contemporary Art at Maine College of Art & Design

522 Congress St., Portland, 207-699-5029, meca.edu/ica

“Objects of Power” (Oct. 4 through Dec. 13) is determined to shake the tree. It’s not exactly news that museums, auction houses and galleries are rife with systems and structures that have slanted advantages toward male Eurocentric artists for a few centuries now. Who gets exhibited, whose works are valued, how prices are fixed – it’s a dirtier business than the white-glove genteel image the art world purveys, with all sorts of exclusionary tactics and hierarchies in place. This show, says director of exhibitions Iris Williamson, “is a selection of stories told by artists dealing with those structures.”

William Villalongo, “A Dance for Dave,” 2023. Acrylic, velvet flocking and paper. In “Objects & Power” at the ICA at MECA&D. Courtesy of © Villalongo Studio LLC and Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC

The 10 artists in this show tackle the complicated and delicate issues of human remains being preserved and possessed by museum collections, repatriation of artifacts to their cultures of origin, an epidemic of erasure and curatorial positionality, to name a few. For instance, Williamson says, “Some think about how objects are kept and held.” Museums have long claimed that they should be the stewards of these treasures because they will take care of them better and engage in more refined scholarship. Legally, they must allow access to them by the cultures to which they rightfully belong. But, she notes, though access gets an initial “yes,” a “no happens in running out the timeline” of appeals and conditions. Sara Siestream’s work in the show addresses some of this conundrum.

Gala Porras-Kim touches upon the issue of human remains in museum collections. And even Williamson examines her own biases as curator. “There’s still gatekeeping happening,” she admits. “I come from a certain point of view and background. So, sometimes, one solution is to give up the responsibility of curating to an artist.” Result? ICA will surrender the front window space, allowing free rein to Portland-based Maya Tihtiyas Attean, a Wabanaki artist raised on the Penobscot Reservation.

University of New England

716 Stevens Ave, Portland and 11 Hills Beach Road, Biddeford, 207-602, 3000, library.une.edu/art-galleries

UNE’s two outposts continue shows that opened this spring. At the Portland campus we have “The Numbers Game,” a group show that revolves around the use of mathematics in art-making. The galleries’ director, Hilary Irons, explains the show’s six women artists “invite us to contemplate how the use of mathematics and numbers-based thinking can further creative activity. Students of mathematics, statistics and other fields requiring their own forms of creativity with numbers will find much to contemplate.” Among these are the Fibonacci sequence-inspired paintings of Grace DeGennaro, the sculptural ceramics of Lynn Duryea, the “Water Shapes” of Emily Haas, Meg Hahn’s “Cut Out Shadows” oil-on-panel works, Munira Naqui’s minimalist paintings, and Alice Spencer’s repetitive pattern-based works.

Alicia Ethridge, “Wind Seeker.” In “Light and Shadow” at University of New England in Biddeford. Image courtesy of the artist

In Biddeford, “Light and Shadow: Motherhood, Creativity and the Discourse of Ability” (through Oct. 20), says Irons, “highlights the creative work of a diverse set of artists who are also mothers of children with special needs. Focusing on the power of their studio work outside any particular reference to their children,” she continues, “it honors the creative autonomy of artists within family structures, and provides a unique window into the lives of parents of differently abled children for students of education and social sciences.”

Yet its appeal really speaks to any mother who has ever tried to manage the many responsibilities required of her and the importance, within that, of personal space – the “autonomy” Irons mentions – to recuperate, contemplate and regenerate.

University of Southern Maine

5 University Way, Gorham, 800-800-4876, usm.maine.edu/gallery

On Oct. 3, USM reopens its galleries with “under/current,” which presents the multimedia work of Stephanie Garon. It incorporates video, sound and mined rocks into an immersive installation. The exhibition summary reads, in part: “under/current explores issues around land claim and mining’s impact on one local economy driven by fishing, clean water, and environmental stability … The artist considers the rock for where it intersects within … water … where extractive mining processes hold their most significant and potentially detrimental impact.”

For the show, Garon interviewed community residents – among them kelp farmers and clam diggers – and consulted with scientists, geologists and naturalists. The exhibit features sound pieces that were collaborative efforts with Passamaquoddy members.

Anyone following community discussions about lithium mining to power cellphones and car batteries is familiar with the ways in which these practices threaten habitats, pollute waters and otherwise create effects that reverberate far beyond the locality where they’re sourced. It’s a reminder about the interconnectedness that is often ignored in the pursuit of capitalist enterprise.

MORE ART SHOWS TO SEE THIS FALL

Center for Maine Contemporary Art

Katarina Weslien takes over the Main Gallery with “I forgot to remember,” a fully immersive and experiential survey of 40 years of work. It reflects, she says, her “deep, ongoing interest in the tactile and metaphoric power of cloth; how mute objects speak; and how objects elicit memories, emotions, and embodied imaginations in the face of impermanence, disorder, and displacement.”

The lobby and hall of the museum will host “From the Collection of Lord Red,” the work of exciting young Maine artist Kyle Downs, who works with basketballs that he cuts into strips and pixels, then reassembles in what can look like ceremonial shields and other ritual objects. His wall sculptures reference, among other things, sacred geometry, post-production practices, pop culture and the psychology of collecting.

Both Sept. 28 through May 4. 21 Winter St., Rockland, 207-701-5005. cmcanow.org

Farnsworth Art Museum

“Andrew Wyeth: 1982” delves into the seemingly endless oeuvre of this artist to present a show focused on the year he turned 65, one that was tumultuous for Wyeth. This late period was rocked by a substantial theft of his artworks, the imminent loss of his dear friend and model Walt Anderson, as well as reconciling himself to the seesaw nature of fame.

Sept. 21 through March 23. 16 Museum St., Rockland, 207-596-6457. farnsworthmuseum.org

Ogunquit Museum of American Art

“Domestic Modernism: Russell Cheney and Mid-Century American Painting” seeks to broaden the concept of mid-20th-century painting to include small figurative work (heretofore in the shadow of the dominant Abstract Expressionism) and the importance of local domestic setting. It was curated by Kevin D. Murphy at Vanderbilt University.

Through Nov. 17. 543 Shore Road, Ogunquit, 207-646-4909. ogunquitmuseum.org

Portland Museum of Art

Sayantan Mukhopadhyay, assistant curator of modern and contemporary art, has been gathering work by a range of young Maine artists for “As We Are,” an exhibition that is like a snapshot of concerns and thematics shared by artists today, including LGBTQ+ issues, climate resilience, our immersion in technology, place-making and more.

Opening Oct. 11. 7 Congress Square, Portland, 207-775-7148. portlandmuseum.org