Rwanda-born, Indian-origin author-curator Amin Jaffer has played a pivotal role in elevating the global recognition of Indian art. Renowned for his scholarly explorations of the interconnectedness between artistic traditions, he is one of the artistic directors for the Islamic Arts Biennale in Jeddah, which runs through May 25. He is also the director of the distinguished Al Thani Collection, assembled by Sheikh Hamad bin Abdullah Al Thani. Former international director of Asian Art at Christie’s, he has authored several acclaimed publications, including Made for Maharajas: A Design Diary of Princely India (2006), and Encounters: The Meeting of Asia and Europe 1500-1800 (2004), that accompanied an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London.

The Islamic Arts Biennale adapts an inclusive approach to the definition of Islamic arts, showcasing objects and artefacts from different periods produced across the globe. In doing so, does it also aspire to initiate new dialogues by revisiting our past?

We refer to the biennale as Islamic arts rather than Islamic art to emphasise that there’s no one canon of Islamic art. The fact is that art is represented in multiple media and many regions. Many artists who have made these objects are Muslim, while many others are non-Muslim, as are numerous patrons. We wanted to emphasise the porous nature of patronage and artistic creation, as well as the exchange of goods, ideas, and commercial exchanges between the Muslim and the non-Muslim world.

The idea is to open up notions of Islam. Fifteen or 20 years ago, an exhibition of Islamic art probably would not have included Indonesian material, because we have a fixation that Islamic art is focused on Arab or Persian art but this exhibition demonstrates that the Islamic world is as vast as it is varied. The faith and practice of Muslims may be built over certain core principles, but local culture and historic antecedents play a significant role in which Islam is articulated. The subtle aspects of faith are determined a lot by the local environment.

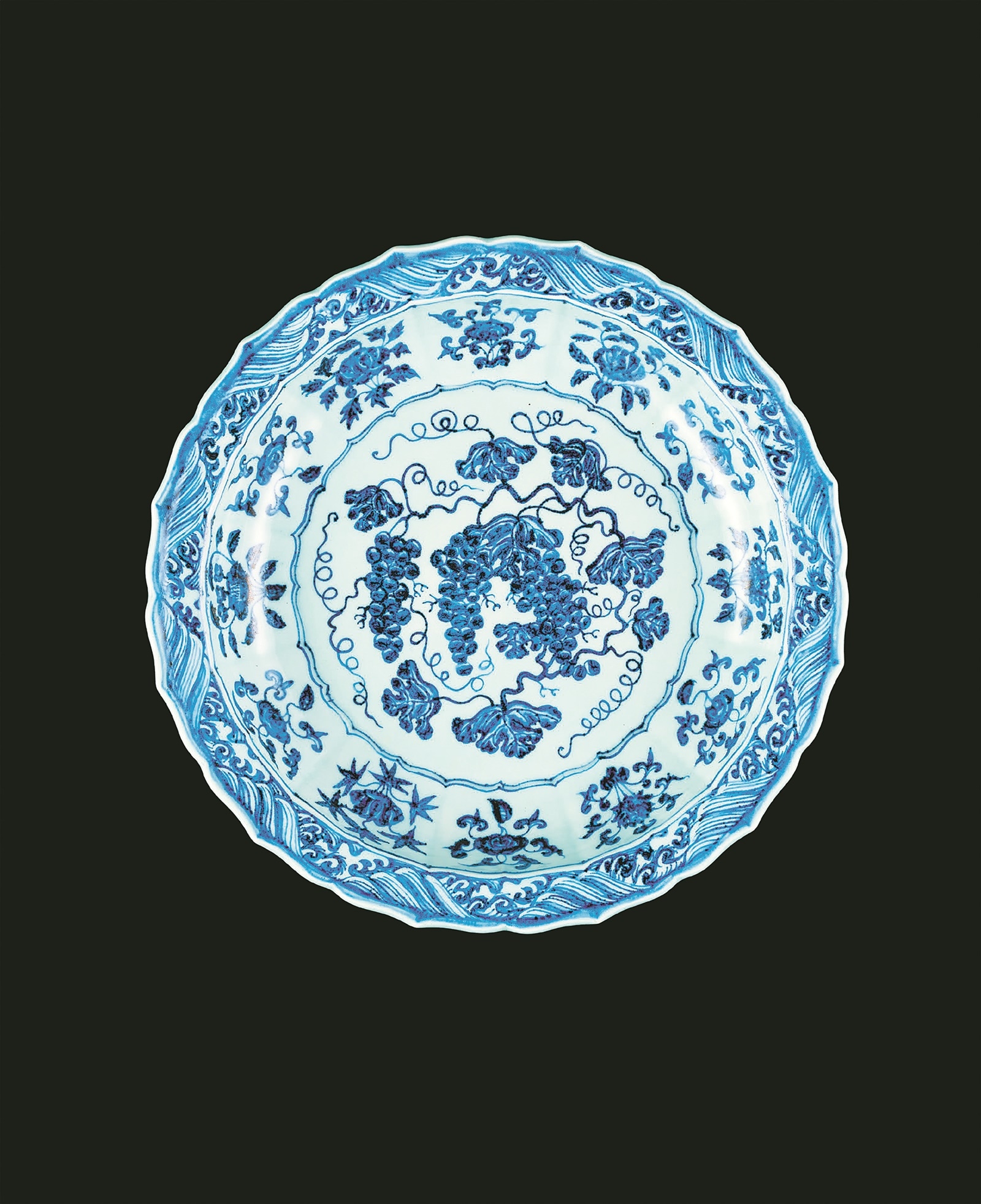

An exhibit from the Al Thani Collection: The Mahin Banu dish, made in imperial Chinese kilns, which was later acquired by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (Credit: Diriyah Biennale Foundation)

An exhibit from the Al Thani Collection: The Mahin Banu dish, made in imperial Chinese kilns, which was later acquired by the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan (Credit: Diriyah Biennale Foundation)

Our theme ‘And All That is In Between’ reflects a liberal, universal, all-encompassing Islam. We also have objects that represent different faiths within Islam.

What are the highlights of the Al Thani Collection at the Biennale (that is part of the AlMuqtani section)?

We wanted to include works of art that are museum-quality and also illustrate the variety in the collection. The works represent the richness and diversity of the Islamic civilisation — from early Quran pages to late Ottoman textiles, works in metal, rock crystal, jade, old miniature paintings. Among the highlights for me are the Mahin Banu Dish (1403–25 CE), a Chinese Ming imperial dish that belonged to Safavid Princess Mahin Banu and Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, and its counterpart, which is a Mughal jade cup carved in the shape of a half gourd that belonged to the Qianlong Emperor and is inscribed with a poem by him. These pieces exemplify the fluidity of luxury goods exchanges between Confucian and Buddhist China, and Muslim India and Iran.

Story continues below this ad

You were born in Rwanda in a Kutchi business family and first visited India when you were 23. How did that impact the course of your life?

It was life-changing. I had read about India, enjoyed Indian food, watched Hindi movies. Growing up, I loved films of Sharmila Tagore and Rajesh Khanna — movies like Amar Prem, Aradhana, as well as Satyajit Ray’s The Chess Players (Shatranj Ke Khilari), and The Apu Trilogy, nostalgia films like Mughal-e-Azam and Pakeeza; among the modern films, Kabhi Kabhi and Silsila. After that, I couldn’t connect with films that were too loud… So, I grew up with Indian culture but from a distance.

When I arrived in India, at the Taj Mahal Hotel in Bombay, I heard a family speaking in Kutchi. That is the first time I heard the language being spoken outside my home. When I made Indian friends and they would serve me typical Gujju meals when I visited them, I knew I was home. This was also the first time I was in an environment where I looked like everyone else, I was anonymous. That had a very big emotional impact on me.

Returning to India wasn’t always easy. I had been raised in a Westernised environment, so I had much to learn. India was also quite closed in the ’80s and ’90s. Nevertheless, it was a homecoming for me. I travelled to Gujarat to locate my family’s ancestral homes. Visiting India at 23 helped resolve my identity crisis. After that, I struggled for many years to obtain Person of Indian Origin status. Initially, I was told I couldn’t qualify because my family had been away from India for generations. It took me many years to receive the authorisation and the status.

Story continues below this ad

How do you perceive the global positioning of modern and contemporary Indian art?

Indian art is increasingly integrated into the global contemporary and modern art scene. Indian artists are more globalised than ever. The future generation of artists will grow up feeling more universal than the previous generation of artists. That’s also a factor of social media, shared education, shared movies, shared media. But I think India is an heir of an early and rich civilisation with unique cultural values which will continue to be represented in the works of its artists. Indian art has a very big role to play in the world.

Do you think we appreciate our ancient and medieval art enough in India?

It is never enough, but there is certainly an appreciation. For instance, in the new Humayun’s Tomb Museum, and the idea of a new National Museum in Delhi. However, the school curricula, not just in India but everywhere in the world, needs to focus on history and the past for the next generation to appreciate works of art from the past. To fully appreciate the present, we must understand the past.