Boston crime legend Myles Connor talks the Isabella Stewart Gardner heist, rock and roll, and his (personally proven) best practices for robbing a museum.

Art thief Myles Connor in Boston on Feb. 26, 2020. / Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

If you don’t have a theory about who robbed the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, are you even really a Bostonian? Thirty-four years ago this month, two men dressed as Boston cops pulled off the greatest real-life art crime of all time. And even though Myles Connor had an ironclad alibi—he was in jail—his name is almost always the first and the last that comes up when you mention the case. On Sunday, March 17, Connor will once again take center stage when he appears at the Regent Theater in Arlington, in conversation with Gardner Museum security director Anthony Amore and Myles’s longtime manager and collaborator Al Dotoli, for the premiere of Rock n’ Roll Outlaw: The Ballad of Myles Connor, a new documentary that examines Myles’s incredible backstory—and what he may know about the Gardner heist.

Born in Milton, Myles Connor was one of Massachusetts’s original rock and roll wildmen—when he wasn’t in prison, and sometimes when he was, he’d gig with backing bands that often included members of Sha Na Na. He quickly graduated to robbing art museums, staged dramatic escapes from jail, and at 23 wounded a State Police captain during a rooftop shootout that also left Myles himself with a few bullet holes. Years later he made a deal with the State Police—which, as I recounted in a recent story for this magazine, earned him the undying enmity of the FBI. His most famous robbery—a crime he once described as the art-theft version of performing at Carnegie Hall—was also the simplest: In the middle of the afternoon, he walked into the Museum of Fine Arts and walked out with a Rembrandt.

Cops escort Connor into a Dedham courthouse in 1985. / Photo by George Rizer/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Famously, Myles used the Rembrandt as a bargaining chip to get a reduced sentence in another case. But by then, Myles was back in jail—so the cloak-and-dagger logistics of returning the Rembrandt to the U.S. Attorney were carried out by his childhood pal Al Dotoli, who had graduated to road-managing acts like Dionne Warwick and Frank Sinatra.

Dotoli is a music legend in his own right. In the ‘60s, the Rolling Stones used a Dotoli-designed sound system while touring behind Gimme Shelter; in the ‘80s, he booked the Stones into a secret gig at a Worcester hole in the wall called Sir Morgan’s Cove. In this century, he’s best known as the guy who books the bands—including the Stones, Sir Paul McCartney, and others—for Robert Kraft’s exclusive Super Bowl parties.

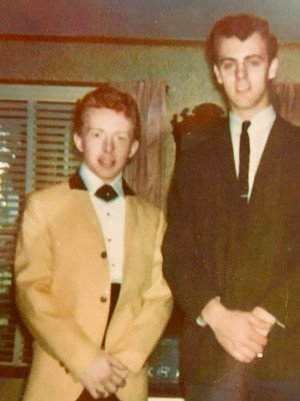

Connor and Dotoli, photographed before opening for the Dave Clark 5. / Courtesy David Bieber Archives

On a recent Wednesday evening, I sat down with Myles, Dotoli, and Rock n’ Roll Outlaw director Bruce Macomber to talk about art, thievery, rock and roll, and the fate of the Gardner paintings. We convened at the David Bieber Archives in Norwood—a vast, last-scene-of-Raiders of the Lost Ark warehouse collection of American pop culture memorabilia that is exactly the kind of place a young Myles would’ve robbed blind in the middle of the night. (Myles’s first words upon entering, his eyes casing the joint: “You got any Japanese swords?”) Among the many treasures in former WBCN and WFNX exec Bieber’s collection is a framed photo of a teenage Myles standing next to the much taller Dotoli, apparently in someone’s parents’ living room, snapped just before the two of them left to open for the Dave Clark 5.

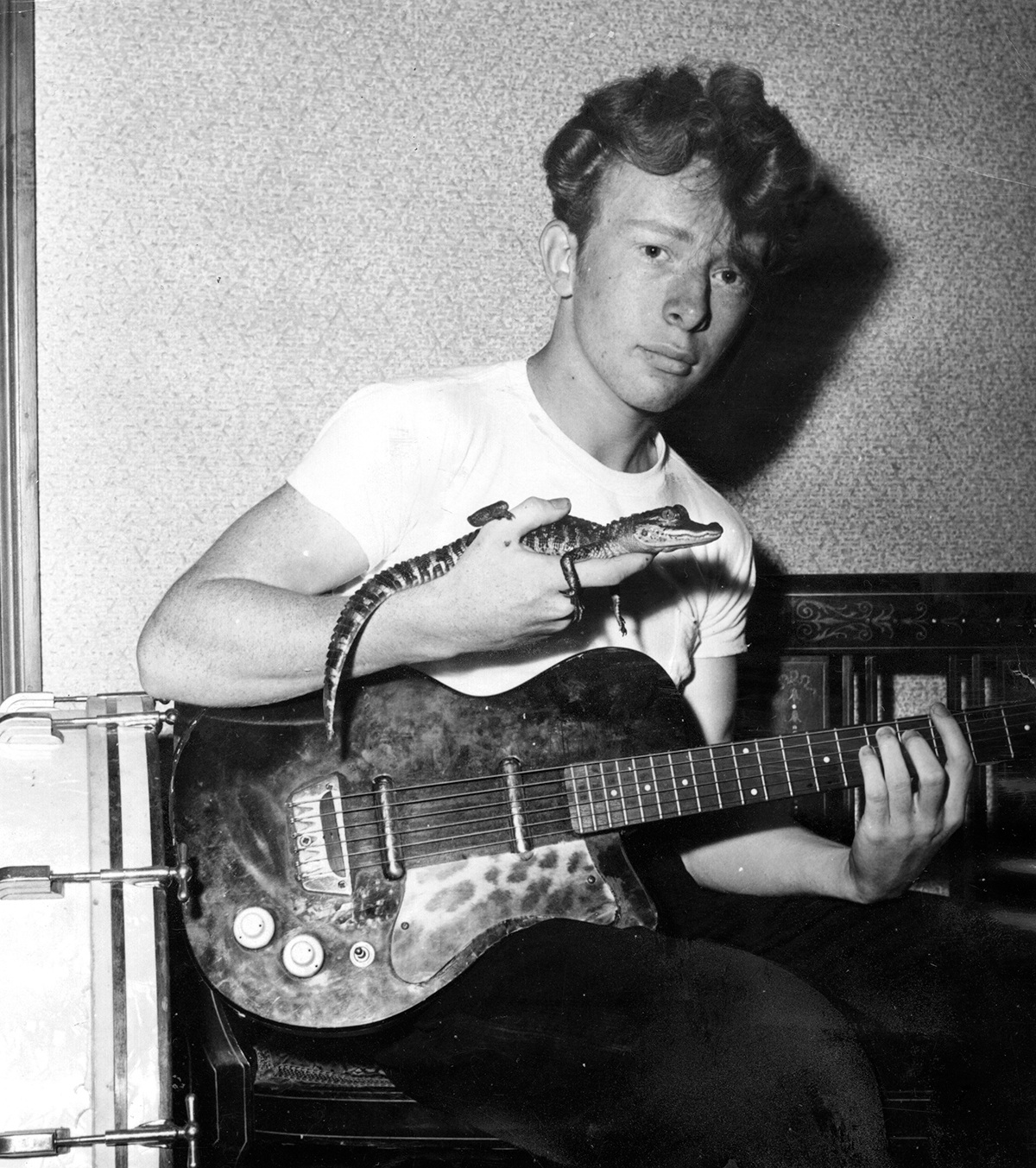

When we spoke, Myles was still steaming about the last time magazine profiled him—he thinks it was the 1970s, director Macomber says early ‘90s—when a long-forgotten author wrote that as a child Myles had grown up running around Cunningham Park in Milton taking potshots at squirrels with a BB gun. His eyes narrowing at me from across the table, he says, “I made a phone call to the magazine and I tried to talk to the guy who wrote the article. What he wrote about me was so untrue—as you may have heard, I am a deep animal lover. I love all animals. I had a big collection of them. I had mountain lions and squirrels and raccoons, every kind of dog, emus, every reptile you can think of.”

Since we couldn’t find the article on short notice, let this stand as our temporary correction: Myles Connor swears he never shot at any animals. Just cops who wanted to kill him. And he didn’t enjoy shooting at those guys, either.

Connor and Dotoli in 2024. / Photo by Carly Carioli

Your father was a Milton police officer. So how did you get mixed up in such a crooked, foul, no-good, dirty business as rock and roll?

Myles Connor: Funny you should ask. I was an innocent guitar player in Milton. And this character [nods at Al] showed up at my house. He was a few years younger than me, but several inches taller than me. And he said, ‘I want to learn how to play the bass.’ And that’s how Al and I met. The first gig I had was at a high school, and he set it up. He always had this acuity of being behind it—whether as a [concert] producer, or a sound producer, or a producer of a band. He was always that kind of a guy.

Al, when you met Myles, did you have any idea what kind of trouble you were getting into?

Al Dotoli: Well, no, I didn’t—but it was exciting and stayed that way for a long time. I asked for it.

Myles, when you were playing roadhouse gigs at the Beachcomber in Quincy, you were billed as the President of Rock and Roll. Who were your musical influences?

MC: There was Jerry Lee Lewis, Fats Domino, Chuck Berry, of course Elvis Presley, Roy Orbison, Dion and the Belmonts. The list goes on and on and on. I liked every one of them. My favorites would have to be Johnny Cash, Orbison, and Chuck Berry. And of course Elvis. Essentially the Sun Record guys.

Connor, 17, poses with his guitar and pet alligator, Albert, at his home in Milton in 1960. / Photo by Hugh E. O’Donnell/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

You also developed a taste for fine art. Who were your favorite artists?

MC: My speciality—the art that I favor—is Japanese swords. But as far as painters go, I think Picasso’s very overrated. I can’t understand why his paintings go for $50 million.

Where did your fascination with swords come from?

MC: My grandfather went to Japan in the late 1800s along with William Sturgis Bigelow and [Ernest] Fenollosa of the Museum of Fine Arts. And at that point, Japan was struggling to get by. So a lot of—in fact, almost all—of the major collections, from the MFA to the Met to the big ones in England and France, they all capitalized on the fact that these people were desperate. My father amassed a huge collection of Japanese swords, and that’s where I got the interest. [At one time] I had a huge collection. Now I have…several.

AD: A lot of [Myles’s] thievery was to buy Japanese swords. It wasn’t for the art—it was for the swords.

Connor Jr. at home in 2010, with a turkey friend. / Photo by John Tlumacki/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

That was going to be my next question: How did you get from rock and roll to art theft?

MC: Well, rock and roll was a lot of fun—playing at clubs and seeing the response of the audience. It was an excitement, and it was enjoyable. But it wasn’t really making the amount of money I’d get from robbing a bank for, say, $165,000—versus back then [I’d make] maybe $500 a week playing the guitar.

Bruce Macomber: [$500 a week] was more than my parents made, okay? Just for a little perspective. It’s not like he was a starving musician.

There are several ways you can rob a museum. [You] could climb up the side of a museum to the roof and go in the attic window, where there’s no alarm. Or you can pretend that you’re somebody else.

You could learn to play rock and roll by watching and listening to your heroes. But how did you learn to steal? You weren’t just sticking a gun in someone’s face—these were crimes that took a fair amount of skill and strategy.

MC: You know who was one of my first influences? Sean Connery as James Bond. He was very physically active in his younger films. And I remember saying, ‘If he can do it, I can do it.’ And I was physically active at the time. My speciality was museums. And there are several ways you can rob a museum. I could climb up the side of a museum to the roof and go in the attic window, where there was no alarm. That’s one way to gain an entrance into a museum.

Or you can pretend that you’re somebody else. And you go in there with a big collection of art that’s equal to what the museum has, or superior to what they may have. And then you show them—and you’re thinking of making a donation.

AD: Instead of a withdrawal!

MC: [You say,] “May I have a look and see what you have in storage?” And that way you get access to their storage. And that way you take things that are never missed. And that’s one of the best ways to get things out of a museum.

What’s the most expensive thing you ever stole?

MC: That would probably be the Rembrandt from the MFA.

You talked about that job a bit in the recent Netflix documentary This Is a Robbery, but you went into greater detail in your 2010 book The Art of the Heist: Confessions of a Master Thief. There’s a point at which Myles is in jail, the Rembrandt has been liberated from the MFA but is still in hiding, and Al is on tour with Dionne Warwick in Europe. Al, did Dionne have any idea that you were being tailed by the FBI and the Mob because they thought you knew where the painting was?

AD: Let me put it this way: I don’t think she had any idea, but she knew I was no angel. And she kinda loved that shit, let’s face it. I went from her to Frank Sinatra, so just take a guess. But no, I don’t think she knew about the FBI. But I will tell you that I became friends with some of the FBI guys who we wound up giving this thing back to. And one of them, he said, “You shittin’ me? We used to fight to follow you. You get to go all over the country, you eat at the best restaurants, stay at the best hotels, see Dione Warwick every night.” They were behind me the whole fuckin’ time!

Richard Abath, the security guard who buzzed the thieves into the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum on the night of the robbery, just passed away. For years, he was suspected of being involved. What are your thoughts?

AD: You mean did he have anything to do with it? No, of course not. The guy was making seven bucks an hour. That was just FBI bullshit before they brought in Anthony Amore.

When [Myles] was in jail, we tried to do something [to locate the paintings] — big-time tried to do something, let me tell you. And we even got [Myles] down to Rhode Island, so we might be able to, uh—well, anyway. I was told by, what was the poor woman’s name? [Gardner director] Anne Hawley. The FBI told them, “You do not want to get those paintings back through Myles Connor. It would be a big mistake. We will get your paintings.” Meanwhile, they weren’t doing one fucking thing.

What they were doing was doing everything to keep away [Myles] and anybody else who could help, but would make them look bad. Eventually, though, Myles and I and our attorneys said, you know, maybe we should get our own detective. The FBI was in charge of this fucking thing for like 20 years.

The empty frames from the stolen art still hang in the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. / Photo by David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Do you think they’ll ever find the Gardner art?

MC: I’d like to think so. On behalf of the people who would love to get it back, I’d like to say I hope someday it’ll surface [and] the people that may have been in a position [to come across the paintings] decide to relinquish them.

But my personal feelings I’ll keep to myself, because Anthony Amore is a good friend of mine, and I know his feelings and my feelings and Al’s feelings may differ. So I’ll just say that they’re in places unknown. I don’t think they’re destroyed—that some guy got paranoid and destroyed them all.

There are places in the world that do have billionaires—Saudi Arabia for instance—and there are other billionaires that have their own private art collections. And they had no [allegiance] to the US, so why would they relinquish? Saddam Hussein had a big art collection, Muammar Gaddafi had a big art collection—Hussein’s art collection was world renowned. He had a bunch of big, big name artists in his collection. That’s not really what people who hope that they’re going to get them back want to hear—that they’re in the possession of some eccentric billionaire art collector.

There’s a zillion crooked people around the world. In fact, I think they went to Japan looking for them. They went to Ireland looking for them. I think they even went to Germany. In those countries, there are eccentric people that have multiple millions of dollars or billions of dollars and they have their own art collections.

So, unfortunately, right now I have no idea where they are. I wish I did. If I did, I’d do everything I could to get them back. Because I know how much they mean to the people at the Gardner, especially Anthony Amore.

AD: We’ve never agreed on much [laughs]. But I will say this: [Myles] was in jail for a long time and I was still hanging out with certain people. And nobody wants to know the truth. That’s what I’d say.

MC: I don’t know his view, but there’s as much credibility in his view as to the view that I just put forward.

AD: We’ve agreed to disagree. Not for the first time. And it just makes no fucking sense to me.

Connor, left, looks on during an arraignment for in Norfolk Superior Court on July 2, 1980. That day, Connor pleaded innocent to charges that he participated in the 1975 murders of Susan C. Webster and Karen T. Spinney of Jamaica Plain. / Photo by Jack O’Connell/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

Al, do you think the paintings will show up in your lifetime?

AD: When you see the film, you’ll know exactly what I have to say. I don’t think that any more than three or four of them could possibly be recovered. And even those three or four are questionable, and I’ll tell you exactly why. It doesn’t really say it in the movie, but the idea was that some people from New York—and [Myles] will be the first one to tell you that some of the mafia from Boston, through Federal Hill [i.e. the head of the New England mafia, then based in Providence] asked him to go down to see these people in New York before he went back to jail.

Okay, so they’re stolen. There’s 13 [paintings]. People in New York say we want number 2, 4, and 5. That puts the theft in motion. And the two people who we believe did this, do what they did. The very same night, the van pulls up. The guys from New York—who were much quicker than the mafia in Boston and the mafia in Federal Hill, believe me—show up with a $40,000 bag. And there was a little story about how stupid these fuckers were to cut [the paintings] out [of their frames]. So when the New York guys came, they had their bag of money, but it’s not just, “Oh, let me have the painting, here’s your money.” They have photos of what should be on the back of it, and they know just what they’re doing. I mean, they’re dealing with criminals—they don’t want to get fucked. So [the thieves] say, “Okay, there’s your paintings,” and [the New York guys] say, “What? Where’s the frames?” “Well, those things—rolled up.” “Wait a minute, I’m not sure I can give you this money, I have to go back and check.”

And there’s some question as to whether [the New York guys] ever returned. So, if my theory is correct—and believe me, the people I’m talking about, they went and saw Myles [in jail] and said, “We did this, we’re gonna get you out of jail.” Alright? So did [the New York] guys come back and give [the thieves] the money? For rolled up paintings? I don’t know, but if they didn’t, then the guy I said destroyed them, destroyed them all.

Rock n’ Roll Outlaw: The Ballad of Myles Connor has been in the works for over a decade—originally it focused on Myles’s rock and roll career, but eventually—inevitably—it began to focus more on his criminal past and questions around the fate of the Gardner paintings.

AD: Then along came Anthony Amore, who would listen to us, okay? So now, that changed the whole fuckin’ scope of it. When the FBI was in charge of this stuff, nothing was ever going to happen. And, I say it right in the movie to Anthony: “If they hired you ten years before they did, you might have your paintings back.” This was not—[looks at Myles] I’ve told you a thousand times, this is not brain surgery. And it’s not some guy in Saudi Arabia or anybody else looking at paintings that had to get from here to Saudi Arabia and nobody saying anything about them for 34 years. That’s my take. Nobody wants to know the truth.

MC: His rendition makes as much sense as mine. The only reason I say Saudi Arabia is, I was being held in Rhode Island—nothing serious—but I bumped into this kid. He said, “I’m a friend of Bobby and Dicky Donati” [brothers who were Myles’s friends and accomplices, long suspected in being connected to the Gardner heist] “and I know what happened to those paintings.” I said, “Really?” He said, “Yeah”—and that’s when he mentioned the guy in New York.

And I remember Dickie took me to meet the guy in New York. And the guy in New York, like [Al] had said—the paintings were taken out of the frames, so maybe they were rolled up, maybe destroyed. And they may have said, “Fuck you, I don’t want to buy them.”

But there was a guy in the Gambino family that made a habit of buying stolen art. And the stolen art market—the black market—is far, far, far bigger than anybody realizes. The concept of, “Oh, it’s one of a kind, there’s no market for it,” well: You can go online and find that there’s a stolen art register and it’s huge. And in it there’s Picassos, there’s all kinds of things that are expensive paintings, you know—I can’t say “one of a kind” because [Picasso] made so many of them, you know.

AD: I was going to say, don’t buy a Picasso!

Rock n’ Roll Outlaw: The Ballad of Myles Connor screens Sunday, March 17 at 2 pm, followed by a Q&A with Myles Connor, Al Dotoli, Bruce Macomber, and Anthony Amore, at the Regent Theater, 7 Medford Street in Arlington. Tickets are $21, VIP tickets—including a pre-screening reception with the filmmakers—are $28.