Stories about the Virgin Mary “have been told by more people, over more centuries, in more countries, and in more languages” than stories about “anyone else ever,” says Wendy Laura Belcher, professor of comparative literature and African American studies. “No other body of literature illuminates as much about how different cultures have made sense of the human and the divine.”

Belcher has led a major research project about a huge collection of these stories from the African continent, which have never been the subject of deep, wide-ranging scholarship outside of Ethiopia. Five years of work by a primarily Ethiopian team of researchers and translators, as well as Princeton undergraduate students, has culminated in the Princeton Ethiopian, Eritrean and Egyptian Miracles of Mary (PEMM) website, a project in the digital humanities.

With her primarily Ethiopian team of researchers and translators, Professor of Comparative Literature and African American Studies Wendy Laura Belcher has brought together 2 million pieces of data documenting Marian miracle stories from the African continent — including more than 1,000 stories written about the Virgin Mary and 2,500 Ethiopian paintings depicting her.

The easy-to-navigate PEMM website includes over 2 million pieces of painstakingly collected data documenting the development of these Marian stories, from the very beginning, to their flourishing in Africa in the middle ages, into the present day.

Website visitors can learn about more than 1,000 stories written about the Virgin Mary, see 2,500 Ethiopian paintings depicting stories about the Virgin Mary and learn more about the 1,000 parchment manuscripts in which the stories appear. The stories and paintings are searchable by date, manuscript, place of origin, language, title and many other categories.

Scores of books about the European “Miracles of Mary” or “Marian” stories — parables which began to circulate in the 1000s — have been published, Belcher said. “But few have studied the African representations of the Virgin Mary, which span from the 200s into the present,” Belcher said. “Through our research, we have discovered that the Marian tradition in Africa is older, richer and more indigenous than previously thought by scholars.”

Among the engaging African stories are one known as “The Educated Daughter” and another about a bankrupt merchant who resists Satan’s offer of great wealth. In them, people pray to Mary for help, Belcher said. “She comes and she does something miraculous directly for you.”

By dramatically increasing access to these early African texts in the U.S. and other English-speaking countries, Belcher hopes that the PEMM resource will help expand humanities scholarship and curriculums into a more global canon.

Found in translation

There are over 1,000 monasteries and 15,000 churches in Ethiopia and Eritrea, Belcher said, and nearly every one has the Marian stories contained in a compilation text called the “Täˀammərä Maryam” (Miracles of Mary), used daily for prayer and read aloud during church services. Each has different stories or different versions of the same stories. “There’s an extraordinary wealth there to be explored,” she said.

As many as 100,000 “Täˀammərä Maryam” manuscripts exist in Ethiopia, yet only a handful of them and their stories had been cataloged or translated into English. The PEMM project has access to 1,000 digital copies, many of them microfilmed in the 1970s and 80s, Belcher said, when the National Endowment for the Humanities provided funding for people to go into monasteries and churches to do this work.

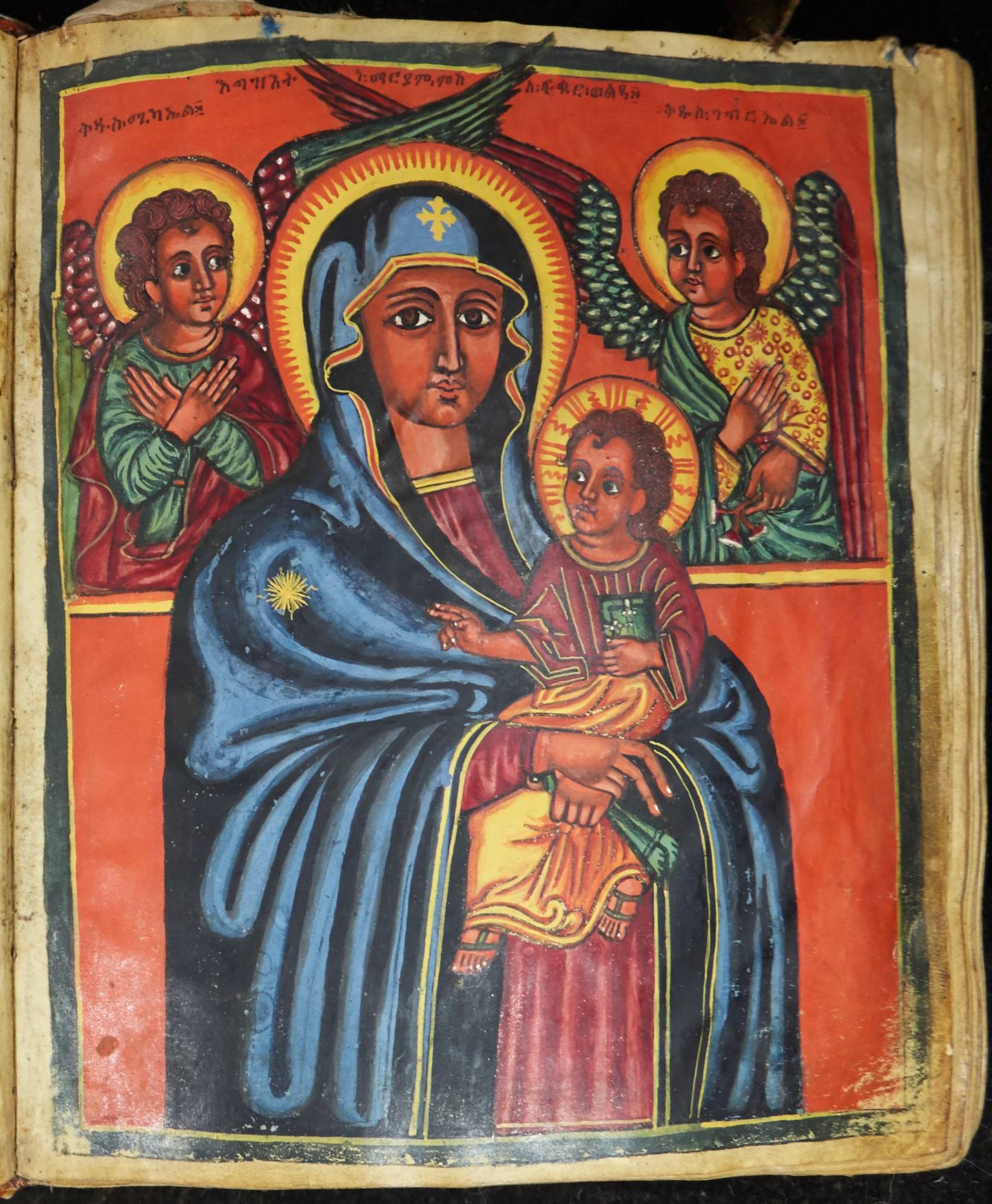

This Ethiopian painting of the Madonna and Child appears in a manuscript dated to 1650-1749 (HMML Project ID EMDA, Manuscript No. 237, s. 4b.) Its PEMM Paintings page has more details.

The PEMM project began at the Princeton University Library, which has the largest collection of Ethiopian manuscripts in the Americas and an unusually high number of Täˀammərä Maryam manuscripts. Belcher estimates that only three institutions outside of Ethiopia have more: the British Library, the Bibliothèque nationale de France and the Vatican.

“Working with translators is my deep joy in life,” Belcher said. “And translating alongside my colleague Mehari Worku has been a particular joy.” In 2020, Worku, an Ethiopian doctoral student at the Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C., reached out to Belcher, asking to participate in the project. He was able to work remotely, along with the two other translators and catalogers, Dawit Muluneh and Jeremy Brown, because the manuscripts were digitized.

“Mehari grew up in the religious education system in Ethiopia and knows the language, the literature, and the tradition backwards and forwards,” said Belcher. “Together, Mehari and I innovated a translation method that he calls ‘colloquial fidelity.’”

Both had found that some translators are too literal and the meaning or nuance can get lost. They were eager for the Marian stories to be clear and lively.

“Once, Mehari had translated a response that Saint Joseph gave to his wife Saint Mary as a simple, ‘OK.’ But when I asked whether Joseph was agreeing readily or reluctantly, Mehari changed the translation to ‘Yes, ma’am.’ Which is just wonderful. That is a terrific example of colloquial fidelity.”

Although Worku grew up listening to the Marian stories, working on the PEMM project revealed new insights and discoveries. “The intense academic rigor the project needed was matched with the joy we received reading and translating these centuries-old stories,” he said.

Worku is most excited to see how people around the world outside academia, especially young people, will engage with the website. “PEMM is a very ambitious academic project aimed at studying this magnificent Ethiopian literary heritage thoroughly and presenting it in a uniquely accessible manner,” he said.

The power of stories passed down through the ages

Belcher lived in Ethiopia as a young child in the late 1960s. Her father, a physician, taught at the Public Health College in Gondar and conducted clinical research.

“There was a literal castle in my backyard,” Belcher said. “There were oxen threshing the grain like in the Bible. There was a descendant of King David on the throne — Haile Selassie. One of my earliest memories is walking up a hill and seeing the scribes writing parchment manuscripts in the monastery. The idea of people writing and creating these books has been with me since I was very young and over time grew into a kind of obsession with manuscripts and text.”

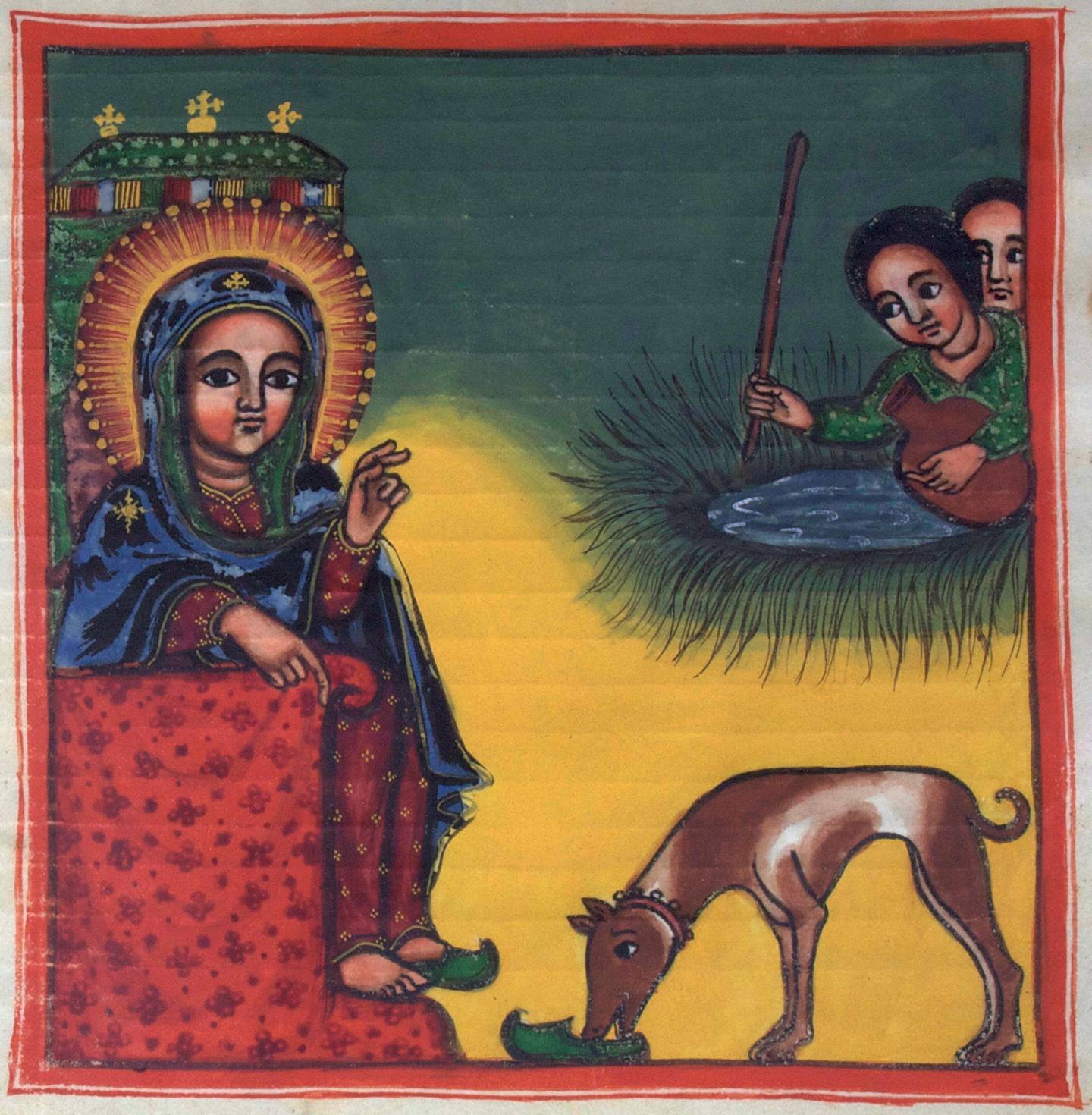

This illumination, from a manuscript dated to 1700-1799, shows Saint Mary giving a thirsty dog water to drink from her shoe. (GG Manuscript No. 43, f. 78r.) Its PEMM Paintings page has more details, including a link to its related stoy.

Belcher’s scholarship focuses on medieval and early modern British and African literature. In 2013, she was preparing to speak on the Marian stories at a conference. She wanted to tell one of her favorites, which, she said, captures both the uncanny nature of these centuries-old parables and why people are so drawn to them.

The story is about a nobleman who commits many truly terrible sins. He comes upon a beggar, asking for just a drop of water from the man’s gourd, in the name of Our Lady Mary.

The nobleman gives the beggar a drop of water and then dies, Belcher said. Demons come to take him to hell, but Mary shows up and says, “He did a good deed in my name, he should go to heaven.”

Christ adjudicates the matter and decides that the single drop of water given in charity counts for more than all his sins, and the nobleman goes to heaven.

People who are looking for forgiveness for their own sins grab on to this story, Belcher said. “They think, ‘If God can have mercy on a man that wicked, then surely me, with my little sins— I can be forgiven as well.’”

When Belcher discovered that there was so little Western scholarship and quantitative research about this whole canon of stories, she was inspired to look deeper. Her research for the PEMM project formally began in 2018, with project managers Evgeniia Lambrinaki and then Blaine Kebede.

Bringing these stories into the classroom

Belcher also used the African Marian stories to form the backbone of a new course, “Healing and Justice: The Virgin Mary in African Literature and Art,” which she taught for the first time last spring and will teach again in spring 2024. She found that her students related to these parables deeply.

“These stories are about the human in the context of precarity,” Belcher said. “Human beings are fragile. They may be ill, disturbed, insecure. These stories cover every facet of the human condition.”

Last spring, the 15 students in her seminar came from a range of Christian traditions, including two Ethiopian Christians and two Egyptian Orthodox Christians, as well as one student who identified as an atheist. “There were so many interesting conversations because people were coming from such different perspectives,” she said. “They engaged in such a beautiful way with these stories and with each other.”

The students found that the stories’ themes easily related to modern-day issues. “One student, who is focusing on disabilities studies, found some gems of affirming stories that she said capture what someone today would want a story to do for somebody with a disability — to accept, to accommodate, to treat with respect,” Belcher said.

Belcher has also involved undergraduates who are majoring in comparative literature in the PEMM project. They wrote story summaries, provided keywords and completed translations.

Belcher hopes that the PEMM website will also be utilized not only by educators and scholars but by members of the Ethiopian community in the U.S. and around the world. PEMM offers “a way of connecting to that heritage,” Belcher said, and one that she hopes will inspire a new generation of humanists.

In 2021, the project was awarded over $600,000 in two NEH grants. In 2023, PEMM was awarded a Princeton Alliance for Collaborative Research and Innovation (PACRI) grant to collaborate with Howard University for two years. In 2018, the Center for Digital Humanities provided support for a two-year collaboration, including data preparation and an outreach program to engage the Ethiopian Orthodox community. The project was then launched as a four-year Humanities Council Global Initiative with support from the David A. Gardner ’69 Magic Grant for Innovation. It has also received support from the Princeton Institute of International and Regional Studies (PIIRS) and the Department of African American Studies, among others.

“I’m so grateful for all that Princeton does for the humanities and its faculty. I can’t imagine this project, on eight centuries of woefully understudied African texts, would have happened anywhere else,” Belcher said.