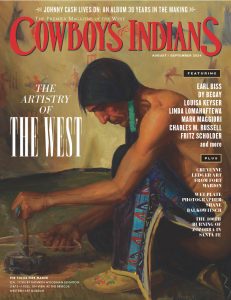

In honor of a piece from their vast collection gracing C&I’s August/September 2024 cover, the Briscoe Western Art Museum chooses 12 works in its collection that capture and celebrate the West.

The Briscoe Western Art Museum uses the tagline “The West Starts Here.” Here, for the Briscoe, is Texas, along the scenic San Antonio River Walk. In its 10 years, the museum’s collection has grown consistently, and its annual Night of Artists has become one of the Western art world’s most anticipated events.

“From beautiful, vast landscapes; Native American life; flora and fauna; Spanish influence and history to the curiosity of exploration and cowboy culture, the Briscoe Western Art Museum’s collection offers a snapshot into the great diversity the West represents,” says Liz Jackson, museum president and CEO. “The West has something for everyone, and the Briscoe aims to deliver that connection.”

It was a challenge for museum staff to narrow its collection to 50 works and artifacts for the Briscoe’s 10-year anniversary book, The West Starts Here: A Decade at the Briscoe. “Even though we’re a young museum, we’re incredibly proud of our collection,” Jackson says.

Being asked to further focus and winnow down the collection to find a “Top 12” for a magazine feature was “akin to asking us to pick our favorite children,” she adds. “Yet each of these works — and the talented artists behind them — represents the genre well, and we’re grateful to have the opportunity to share them at the Briscoe.”

These examples bring a rich context presented by an array of both historical and contemporary artists. “Looking over the last 10 years — and these fabulous works — inspires us to go even further in our next 10 years as we continue to grow our collection and spotlight con-temporary artists who illustrate both the historic and the modern American West,” Jackson says. “That’s what fuels the Briscoe and our collection. The stories these works share need to be told.”

Oscar E. Berninghaus (1874 – 1952)

Cowboy Mess Camp, 1912

Oil on canvas, 21¼ x 45¼ inches

Gift of the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

Berninghaus was a founding member of the Taos Society of Artists, which formed in 1915 and is credited for exposing audiences to new cultures, visions, and landscapes — in turn making Taos one of the most important art colonies in America at the time. A pivotal artist best known for his paintings of Native Americans, Berninghaus painted this work prior to the founding of the Taos Society. It presents a more romantic narrative of the Old West, displaying the camaraderie built during cattle drives in the mid-to-late 19th century in the great western plains and prairies.

Charles M. Russell (1864 – 1926)

Where The Best Of Riders Quit, Modeled 1921 – 1922, Ca. 1954

Bronze, 14¼ x 11¼ x 8 inches

Gift of the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

What Western art museum would be complete without a bronze statue by quintessential cowboy artist Charles Marion Russell? Where the Best of Riders Quit is a small, action-packed bronze that shows The Kid’s modeling ability and his firsthand knowledge of the Old West cowboy life he depicted. For an exhibition of Where the Best of Riders Quit, Russell’s wife and foremost promoter Nancy wrote a description: “The old-time cowpuncher knew his horse, and it was often a battle of wits when he was breaking him to ride. This horse is making a fight and is figuring on landing on his rider. This rider, being of the best, is thinking, too. As the horse comes up, the cowpuncher will grasp the horns and be in the saddle when he gets on his feet again.” This bronze, one of only 15 casts that were produced, is fittingly located in the museum’s lobby, so visitors are welcomed to the Briscoe by one of the founding fathers of Western art. Look closely at the sculpture and you’ll see that it’s signed on the base, directly beneath the horse’s back legs, “CM Russell” with his trademark bison skull cipher.

Mark Maggiori (B. 1977)

Once Upon A Time, 2020

Oil on canvas, 36⅛ x 34¼ inches

Gift of the artist

When French cowboy artist Maggiori presented Once Upon a Time to the museum, he also presented a note that read in part, “May this painting inspire and open the eyes of generations to come, as it shows a part of the West that was sometimes forgotten.” The painting is a visitor favorite, and it’s no surprise why. “Painted and gifted to the museum by the artist during the turmoil following George Floyd’s murder, Maggiori’s dynamic composition consisting of billowing clouds and expansive landscape not only commands the viewer’s attention but also highlights the often-untold story and importance of Black cowboys and their role in the West,” says Jason Kirkland, director of exhibitions, collections and education at the Briscoe Western Art Museum. “The title of the painting helps remind us of their critical role in our nation’s history.”

Maynard Dixon (1875 – 1946)

Two Packers, 1936

Gouache on illustration board, 24 x 20 inches

Purchased with funds provided by the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

Two Packers reflects Dixon’s strong background in illustrative art, a field that launched the Western genre and the careers of the fathers of Western art, Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington. Suggested to be a study for a larger work whose commissioning failed, this evolutionary piece shows a history of Natives transporting goods, illustrating historic and modern transportation methods.

Carl Rungius (1869 – 1959)

Rainbow Rams, Ca. 1945

Oil on canvas, 16¼ x 20¼ inches

Gift of the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

Known as one of the “Big Four,” Rungius was, and remains, one of the leading American wildlife artists, painting vastly in the western United States and Canada. In this work, he depicts three Rocky Mountain bighorn sheep in his classic impressionistic style, showcasing the animals in their naturalistic state. It’s a fantastic reminder of one of the pillars of Western art: wildlife and landscape — representing so much of what we love about the “wild” West.

Fritz Scholder (1937 – 2005)

Native With Blue Blanket, N.D.

Acrylic on canvas, 18 x 12 inches

Gift of the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

A formally enrolled member of the California Mission tribe of Luiseños, called the La Jolla Band of Luiseño Indians, Scholder once vowed to “never paint an Indian.” But his career took a much different path and his body of work largely confronted stereotypical portrayals of Native Americans, dealing with controversial subjects like alcoholism, cultural clashes, and joblessness. His use of bold swathes of color and expressionistic style, shown in this painting, helped bring Native American art into the larger sphere of contemporary art. His dialogue of colors makes for a dynamic, unromanticized portrait. Scholder was one of the first faculty members of the Institute of American Indian Arts, formed in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1962. There, he observed his students’ reactions to the social issues and emotional repercussions of longstanding government policies that affected Native Americans and used his art to address them.

Howard Terpning (B. 1927)

Steer Roping, 1975

Oil on masonite, 23⅞ x 19¾ inches

Gift of the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

Terpning captures the fast-paced drama of the rodeo arena and the American cowboy tradition of steer roping — a rare subject for the artist. Guided by several pencil sketches done in real time, Terpning uses these to construct his overall compositions, bringing together the swift movement and hard work of cowboy culture. The illustrative nature of this piece reflects the influence of Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington, whose works are touchstones for Cowboy Artists of America, an artist collective formed with the intent of keeping alive traditional realism in Western art and of which Terpning was an early member.

George Hallmark (B. 1949)

Reverence, 2011

Oil on linen, 48¼ x 36 inches

Purchased with funds provided by John T. and Debbie Montford

Hallmark’s Reverence indeed suggests the Texas artist’s longstanding reverence and affinity for Spanish colonial architecture, a favored subject in his work, and in this case Mission San José. Through a sense of mood and memory, this painting highlights the mission communities of the past and their lasting significance today. The San Antonio and South Texas connection to this painting is important and signifies the Briscoe’s illustration of the Tejano and vaquero influence on the West. It’s also a wonderful connection to San Antonio’s five Spanish colonial missions, the only UNESCO World Heritage Site in Texas. After a stellar 50-year career, Hallmark is retiring this year, amplifying the significance of having this work in the museum’s collection. He was honored for his lifetime of artistic achievement during the Briscoe’s 2024 Night of Artists exhibition and sale, an event he has participated in since its inception 23 years ago.

Albert Bierstadt (1830 – 1902)

Study of Mount Corcoran, Ca. 1875

Oil on canvas, 26 x 35⅞ inches

Gift of the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

Today, the 13,701-foot summit in California’s Sierra Nevada mountain range is known as Mount Langley. But, in 1868, Bierstadt named it Mount Corcoran in honor of banker and art collector William Wilson Corcoran. “This German American artist joined several journeys of the westward expansion to paint scenes like this that exemplify idealistic portrayals of the great American West and all its grandeur,” Kirkland says. “The Briscoe is proud to exhibit this study, which informed the larger work completed by the artist between 1876 and 1877, and which now hangs in the National Gallery of Art.”

Kathryn Woodman Leighton (1875 – 1952)

The Sioux Fire Maker, Ca. 1930

Oil on canvas, 44⅛ x 36 inches

Purchases with funds provided by the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

This beautiful painting of a Sioux fire maker comes at the hand of a New England female artist, whose interest in Native American subjects wasn’t piqued until an invitation from the great Charles M. Russell in 1925 to visit Glacier National Park. Russell introduced her to the Blackfeet Nation, including famed Chief Two Guns White Calf. Leighton fell in love with the area and the people, returning often to paint the tribe. Her close association with them led to her being given the ceremonial name Anna-Tar-Kee, “Beautiful Woman in Spirit.” Longing to visually display the “vanishing American,” Leighton boldly captures the rich traditions, customs, and attire in this striking painting. The Briscoe’s Women of the West gallery features a growing body of work by female Western artists, and Leighton was one of the first in this genre.

Allan Houser (1914 – 1994)

Pueblo Potter, N.D.

Bronze, Ed. 1 of 20, 21½ x 6 x 1½ inches

Gift of the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

The Briscoe is proud to have several great examples by the Native American sculptor Houser, one of the most renowned artists of the 20th century. A prolific Chiricahua Apache artist and educator, he taught at the respected IAIA, where he initiated the department and gained his status as one of America’s foremost modernist sculptors, eventually retiring from teaching to begin working on his art full time. Together with Fritz Scholder, Houser influenced a generation of Native American students — an influence that continues today for both Native and non-Native artists.

Martin Grelle (b. 1954)

Crooked Lance, 2002

Oil on linen 20 x 20 inches

Gift of the Jack and Valerie Guenther Foundation

Grelle is one of the most influential Western artists today. “Grelle pays homage by accurately depicting the tribal clothing, accoutrements, and hairstyles of a Plains Indian, while transporting the viewer to an imagined scene amid the Western landscape,” Kirkland says. “Rich in symbolism, the story is set as the Native could be headed into battle or a bison hunt.”

From our August/September 2024 issue.

The book The West Starts Here: A Decade at the Briscoe is available for purchase. Follow the Briscoe on social media @BriscoeMuseum.

PHOTOGRAPHY: Courtesy of the Briscoe Western Art Museum