When Thom Yorke left art school in the late 1980s, he found himself “resistant” to calling himself a visual artist—something the Radiohead frontman is only now coming to terms with. “It’s an odd thing to go to art school,” Yorke tells The Art Newspaper in an exclusive interview. “All the way through you’re told you’re going to be an artist but when you leave you think, clearly you’re not going to do this for a career, because no one does that. And then you go into this weird limbo.”

For Yorke, that “weird limbo” led to him and his bandmates forming Radiohead, one of the most successful and critically acclaimed bands of all time. In 1991, the group signed a six-album contract with the leading record label EMI, separating Yorke even further from his artistic roots and compounding a sense of “embarrassment” around his “priority of making music, sound and words”, he says.

York was unhappy with the music label’s generic approach to the art for the band’s first album, Pablo Honey, which featured a baby’s face at the centre of a yellow flower, circled by sweets. Ahead of the next, The Bends, he called Stanley Donwood, who had studied fine art and English literature with him at Exeter University, for his input. The first thing they did was to go and look at rows of vinyls in the music store HMV in Oxford, where Yorke and his bandmates are from.

It is in the city’s Ashmolean Museum that Yorke and Donwood will open their first institutional exhibition, This is What You Get, this week.

Writing in the catalogue for the show, which charts 30 years of record covers starting with The Bends, plus previously unpublished sketchbooks and recent paintings made by the pair, Yorke says his unease around claiming to be an artist was “perhaps a response to the climate of the UK music industry at the time”. Back then, he adds, there was a notion that “a musician could not possibly be an artist and vice versa”—something he now admits is “total nonsense”, particularly given how intertwined Radiohead’s sonic and visual art forms are. As Donwood puts it: “Both of [the art forms] evolve at the same time and neither of them are fixed, it’s like chasing smoke.”

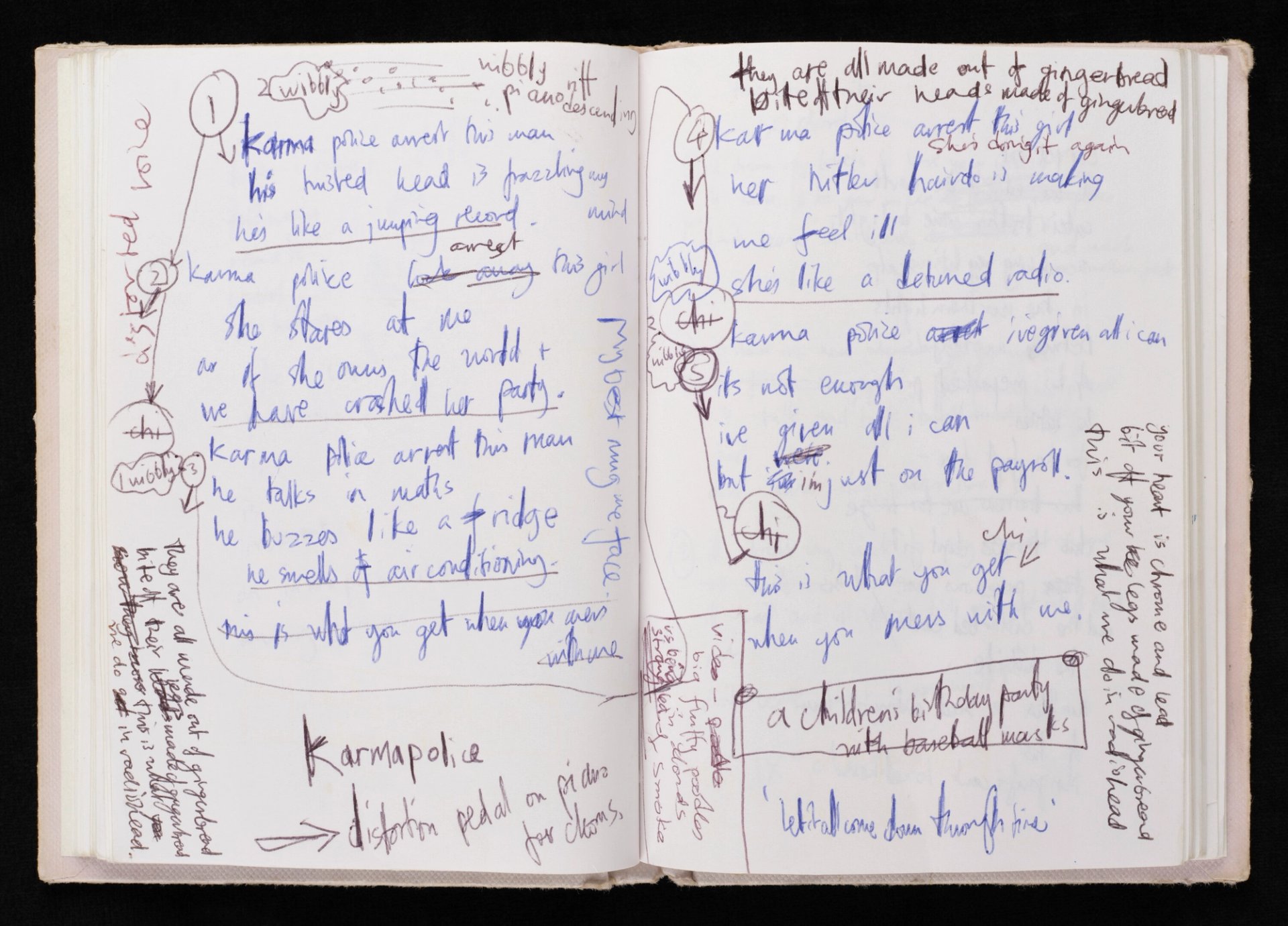

Thom Yorke, Notebook featuring lyrics for Karma Police (1995)

Collection of the artist. © Thom Yorke

If the music industry felt rigid, the art world also presented its own barriers to entry in the 1990s and early 2000s. “There was a strong feeling that the art world wasn’t relevant to our lived experience, it seemed to be its own self-perpetuating system,” Yorke says. “That’s why we found record covers more interesting because they were everywhere. There was the art that people were collecting, and then there was the art that people were experiencing.” In that “third space”, as Donwood calls it, they cocooned themselves from critical scrutiny, allowing themselves to work freely and make mistakes.

That is clearly changing—not least with their first museum show, which Yorke describes as a “big step, very odd”. The exhibition has garnered mixed reviews, which has sparked a conversation in the British press around some of the issues of art world exclusivity Yorke and Donwood are vocal about. As the Independent puts it: “Art snobs beware, for this is a marvellously accessible exhibition.”

Over the past few years Yorke and Donwood have been dipping their toes in the art establishment in other ways, too. The pair have been represented by Tin Man gallery—with spaces in London and Hampshire—since 2021 and exhibited at Christie’s during Frieze London the following year. An architecturally ambitious plan for an exhibition at London’s Victoria & Albert Museum was shelved after the pandemic due to logistics and restrictions imposed by the local council—though a digital version of the show was produced instead.

Independently, Donwood (whose real name is Dan Rickwood) has had a long and successful career as an artist but he has often operated on the periphery of things, working among graffiti and graphic artists. He has been inspired, he says, by figures such as Barbara Kruger and Jenny Holzer who have often used billboards as their medium. For the past two decades he has designed the poster for Glastonbury Festival.

Today, Yorke and Donwood still have differing views on how their working relationship has unfolded. Though Yorke is finally acknowledging the extent of his part in their 30-year collaboration, he still describes his role in many of the older works as “supervisory”. Donwood disputes this take. “We would both work in front of the same canvas, taking turns until someone won, which was usually me. And then whoever won would get to carry it on,” he explains. “It’s a very young man thing to do, we’re a bit more chill about it now.”

Recognition as a duo

It is perhaps this relaxed approach that has led to the reattribution of two paintings from 2000, Get out Before Saturday and Hotels and a Swimming Pool, created at the same time that Radiohead released their fourth album, Kid A. Previously solely attributed to Donwood, the works are now attributed to both artists and are on show at the Ashmolean.

For the best part of two decades, technology played a key role in their creative relationship. In 1993, when Donwood first started collaborating with Yorke, the pair would go out and take photographs and then film the developed pictures and play them on a television, only to photograph the moving images again. The cover shot for The Bends, of a CPR dummy’s lips parted in ecstasy, was taken by chance after the duo gained access to the John Radcliffe Hospital in Oxford. There, they intended to shoot an iron lung—the title of a song from the album. Finding the grey metal box visually underwhelming, they stumbled on the dummy in a dimly lit room and Donwood immediately snapped that instead.

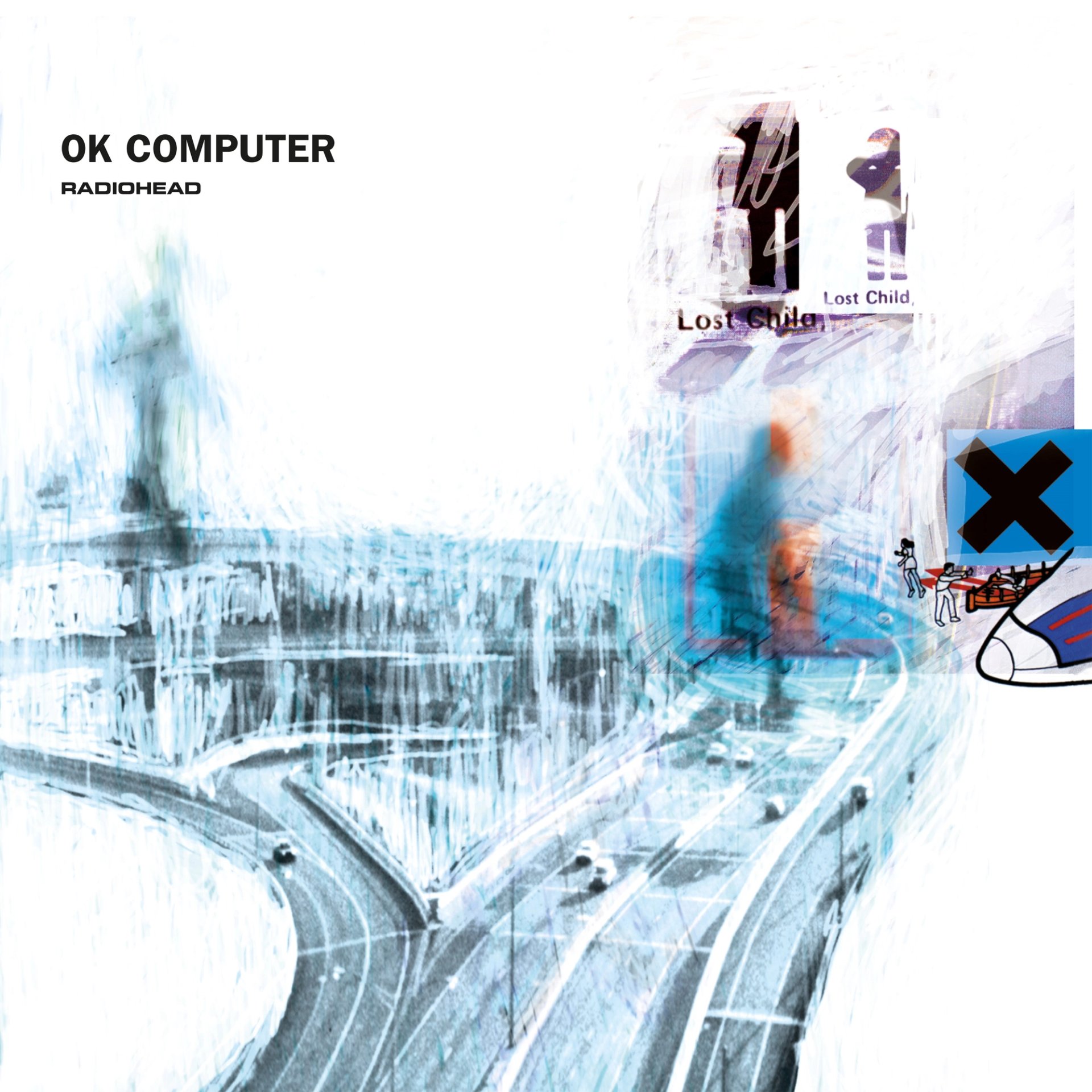

Next came Ok Computer, which propelled the band to stardom. It was also the first time Yorke and Donwood worked together entirely digitally. By then, Yorke was frequently on tour so they began collecting images, photographs, sketches and snippets from books—scanning them and putting them all in a shared digital folder. “I’d pick up something he’d done, erase part of it and put something else in, then I’d hand it back to him. Back and forth, back and forth, endlessly,” Yorke says.

It was also “an odd time for me personally”, the artist recalls. “I’d been living in a bubble for a very long time, touring endlessly and feeling like everything was moving too fast. It was a little bit out of control.”

Thom Yorke, OK Computer (1997)

© 1997 XL Recordings Ltd

The album and its cover reflect this sense of paranoia and placelessness. The image is based on a photograph of a highway interchange in Connecticut, US, apparently taken from the window of a Hilton hotel that Radiohead stayed in after a show in August 1996. Donwood had upgraded from a mouse to a tablet and stylus, which allowed him to draw as well as erase things digitally. But he and Yorke decided they were not allowed to use the “undo” function and had to instead rub out unwanted elements using a crude “wet edge” tool. The resulting work of art is blurry and white, more trace than image.

In the late 1990s, Radiohead began producing their fourth album, Kid A, in an abandoned cinema in Paris. Tired of working on a small screen, Donwood introduced enormous canvases measuring six square feet. “I thought, what if we get canvases that are actually too big, bigger than we can reach over and we work on those instead,” Donwood says.

So, they began painting—something neither of them had done since art school. “It was absolutely terrifying,” Yorke recalls. Donwood had started to use Artex, applying the material to canvases with a palette knife to create a surface of peaks and troughs. “We weren’t even painting for the sake of painting,” Yorke says. “We were painting to build texture, things that we would then scan, because we understood that scanning and photographing dynamic actions was more exciting.”

Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, Get Out Before Saturday (2000)

© Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke

At this time, Donwood would create the paintings, while Yorke would manipulate the digital images. “Dan would do the analogue bit and I liked endlessly tweaking,” Yorke says. “We were both really excited about the vitality of the physical act, plus something that’s happening in post-production and both meeting each other on the same level, as if they’re the same thing.”

Donwood has also worked with Yorke on his separate projects, though for the solo album The Eraser, and for Amok by Atoms for Peace—a band Yorke formed with the Red Hot Chilli Pepper’s bassist Flea among others—the art was made by Donwood and pre-dates the album.

Lockdown and landscapes

With later Radiohead records such as A Moon Shaped Pool, the pair returned to a more collaborative way of working. It wasn’t until the pandemic, however, that they made a huge leap in their shared painting practice. Shortly after lockdowns were lifted, the duo started jointly working on canvases for Yorke’s new band The Smile, painting side-by-side in a shipping container in Yorke’s garden in Oxford. Inspired by an exhibition of Medieval Arabic maps they had seen at the nearby Bodleian Library, the work began to take on a two-dimensional quality; landscapes as if seen from above. Landscapes, it turns out, are the enduring theme from the past 30 years of their artistic output.

In these most recent works, there is a fluidity and depth of colour not seen before. “The thing that was most exciting was when we started working with gouache,” Yorke says. The singer also notes how the pandemic afforded him the time to paint. “Suddenly we could spend a week together just working on these things without the studio being involved, without me having any other distractions. That was eye-opening and deeply therapeutic.”

Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke, Wall of Eyes (2023)

© Stanley Donwood and Thom Yorke

Yorke says he still struggles to meet the demands of life in a post-pandemic world. “When the pandemic finished, a lot of creative people were paralysed by the flashing lights starting again,” he says. “I’m still struggling with that now. Everybody talks about the flourish of anxiety, but I think there’s more to it than that. I really valued that time, and it’s hard to come back to whatever that was.”

Nonetheless, Yorke is now determined to spend more time in the painting studio. “That’s our priority, because we’ve both been skittering around a lot, and I’ve not had a place to work,” he says. Donwood nods. “In the autumn we’ll get into the studio. But for now, all I can see is this show, it’s taken everything.”