Lucy Heyman is a performance health and psychology coach; Rhian Jones is a freelance music writer. They collaborated on the 2021 book “Sound Advice: The Ultimate Guide to a Healthy and Successful Career in Music,” which has an updated, international edition publishing on Nov. 14. Variety welcomes responsible commentary — contact music@variety.com if interested.

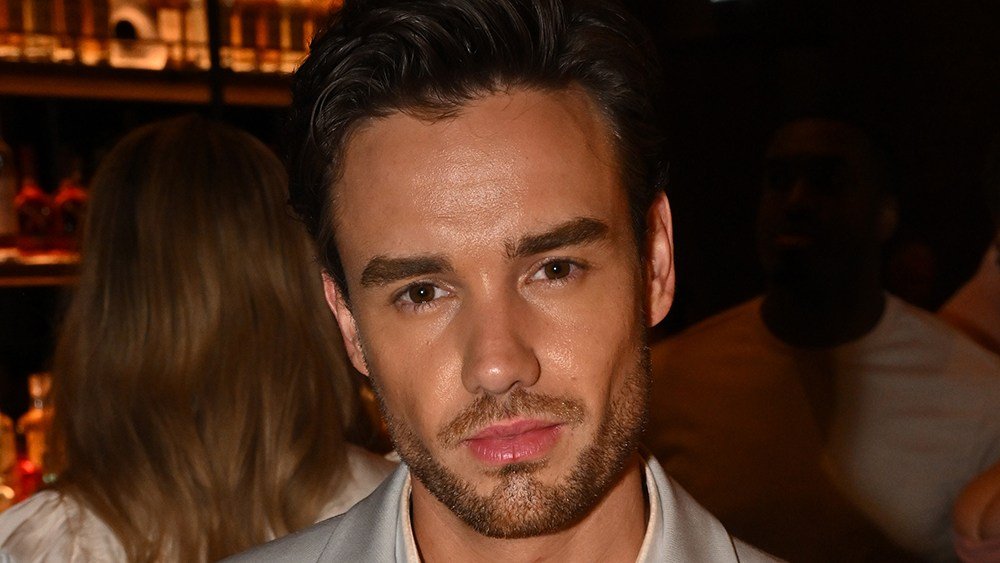

The tragic death of One Direction member Liam Payne at the age of just 31 has once again sparked discussion around the pressures of the music business and its impact on performers, particularly young ones.

Katie Waissel, Payne’s fellow contestant on “The X Factor” — the British television competition where One Direction formed in 2010 — said his death “serves as a painful reminder of the systemic neglect that persists” in the music industry, where the focus remains on profits rather than looking after the people who work within it. “The negligence of duty of care has once again led to a heart-wrenching loss,” she wrote.

Social media has dramatically intensified the pressures of fame, delivering an unnatural level of adoration as well as vicious criticism within seconds. As the family and friends of Payne have experienced, this short-sighted and hurtful commentary, posted by people who can remain anonymous, even continues in death.

Many musicians have been vocal about the downsides of what can appear to be, on the surface, a luxurious lifestyle. Billie Eilish has said she lost out on the fun of her teen years due to work, and Justin Bieber has talked about the loneliness and isolation that comes with feeling trapped in a hotel room while fans and paparazzi circle outside. As Lady Gaga has said: “As soon as I go out into the world, I belong, in a way, to everyone else. It’s legal to follow me, it’s legal to stalk me at the beach.”

While all of the above would be difficult for anyone to handle, there’s evidence to suggest that some musicians might find the nature of a public life particularly challenging. Increasing numbers of artists are opening up about their ADHD diagnoses, and Payne was one. It is hardly surprising — ADHD and creativity are linked, with those experiencing it often finding it easier to come up with ideas, like, for example, writing songs. However, fame poses complex issues for those with ADHD, thanks to the problems with impulsivity, inhibition and risk-seeking behavior that this condition brings. There’s also a growing link between ADHD and addiction.

Because of the lack of structure that comes with life as a musician, and workplace norms you’d hardly associate with a “proper” job, alcohol and all kinds of drugs can be very easily accessible and are often socially acceptable. Payne was open about his own struggles with substance abuse. Drugs and alcohol can be excused in the studio as tools to “heighten creativity,” substances are consumed at all hours, and late nights and late mornings enable a multitude of excess. Throw in the pressures of the job — maintaining a certain level of perceived success; performing live, in interviews and in the studio — and it’s easy to see how one might develop dependances.

There’s yet another important aspect to Payne’s story. After spending six years as part of One Direction, and becoming one of the best-selling boy bands of all time, that rare high didn’t continue into his solo career; while details are unclear, sources say Payne’s business affairs were in an unsettled state at the time of his death. The loss of identity this can cause cannot be underestimated, especially when you’ve been thrust into, and gotten used to, an extreme lifestyle before you’ve even reached full maturity — from a brain-development perspective, that doesn’t occur until a reaches their mid-to-late twenties; Payne was 17 when he became a superstar. Psychotherapist Tamsin Embleton explained the impact of this in the Elevate Music Podcast:

“The industry is all-encompassing, so your sense of who you are and your support network is often sourced within the industry. When that’s wrenched away, it can be really devastating. You can be left with low self-regard, identity issues, issues around belonging, and relevance. There’s a big loss of not just the role, your job, but maybe your identity or a sense of abandonment by the team, so you can be left feeling really hopeless and isolated, rejected and ashamed.”

Payne’s death has placed renewed scrutiny on a music business that deserves it. That’s not to say that there isn’t evidence of progress in this area — the work of non-profits like MusiCares, which provides health and welfare services to the music community; Sweet Relief, a fund for musicians and execs who are struggling with health and other issues; and mental health resource service Backline is ongoing and essential. At the same time, continued open discussion about the issues faced by musicians is encouraging. There are various mental health initiatives at major labels and management companies, all of which are moves in the right direction. Alcoholics Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous and SMART Recovery can provide help to all people who are struggling with substance abuse issues.

Still, a total culture change is clearly not moving fast enough. As Chappell Roan, who has recently cancelled tour dates due to exhaustion, has said: “If you don’t protect yourself, you flourish. If you don’t look after yourself, you can have a pretty big, amazing career. We all see what happens if you don’t prioritize your health.”

What could the industry do to better protect its artists in future? Top songwriter Guy Chambers has called for a ban on allowing under-18s to join pop bands. His collaborator, boy band veteran Robbie Williams, has called for change with the way society deals with fame. There are also things that should be obvious, like being mindful of balance and time off when booking schedules. Therapy, from a specialist familiar with the music industry and fame who doesn’t have conflicts of interest, should be a given, as should support for artists who’ve experienced success and had to make the tricky transition back to “normal” life. This is especially important for those with ADHD or autism. Training for people working with artists in substance misuse could help others spot issues early and offer support and stop all business engagements when it’s clear there’s a problem.

Looking at how children are safeguarded in other industries provides no shortage of examples for care. The aim of such policies is to protect minors from behavior that could adversely affect their mental health or development (which is almost guaranteed when becoming a teenage pop star). For the music industry, this might include criminal record checks for those that work with children — essential for anyone working in an educational setting in the UK — with activity monitored and held accountable. Licensed chaperones who accompany artists to engagements, acting as advocates to protect them and speaking up on their behalf, is another potential solution.

Ultimately, smoothing the rocky road of a path to stardom will be a work in progress, with different measures working for different people. But it’s essential that those working in the music business take it seriously in order to address deep-seated issues that are clearly not disappearing over time.