When we call someone a landscapist, the reflex action is generally to think of scenic painting. A new exhibition at Hobart’s Bett Gallery is an unlikely pairing of landscape artists, and is testament to the diversity of the genre and, more so, the push-away from pigeonholing that it may encourage.

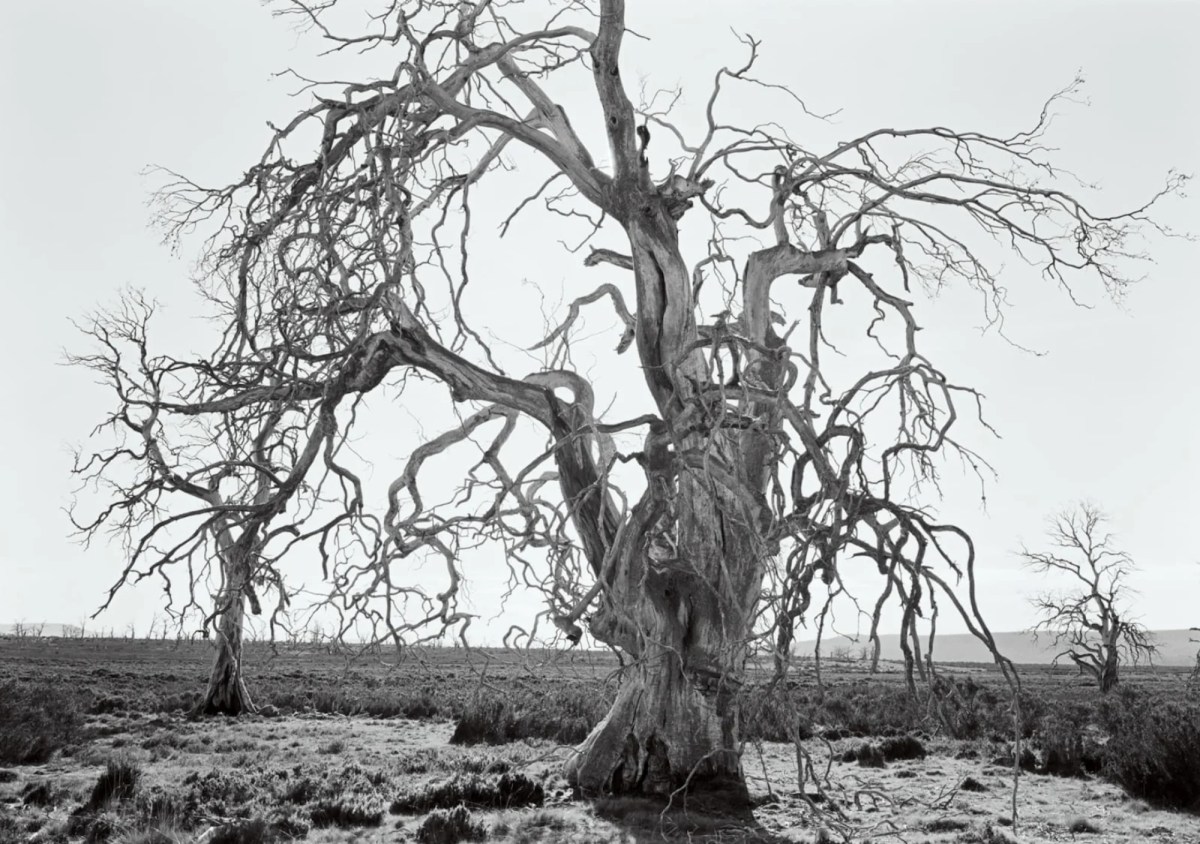

David Stephenson is a photographer working in dramatic black and white silhouette imagery. For his new exhibition, Bone Country, he presents sun-bleached objects – be they a tree or the carcass of an animal – to speak about a landscape.

For Neil Haddon, in the adjacent gallery, landscape is a journey traced through colour and material, and jostling in a complex web of references. Titled Waymarking / Painting / Undertow – and effectively approached as three bodies of work – it thinks through his own journey from the UK, through Spain to lutruwita/Tasmania, alongside migration legacies, and is deeply layered, both physically and symbolically.

Both artists are former winners of the $100,000 Hadley’s Art Prize (which opened the same weekend as their exhibition), and have established careers in the Tasmanian art landscape. Stephenson has been working for four decades, while Haddon has been making and teaching for over 30 years.

Read: I’m an artist in my twenties, and I don’t want to leave Tasmania

Simply, that experience brings a clarity in their work, and confidence to deliver a cohesive and resolved exhibition. Perhaps that is why the pairing works. There is no competition between the two bodies of work, and there’s no forced connection.

Stephenson’s images are immaculate in their presentation. But, rather than just deliver us pretty hero images of the landscape, he draws attention to an ecocide we are living through – in particular the clearing of land in Tasmania.

It is most dramatically narrated in a suite of large tree portraits along one wall, their titles simply drawn from their locations. They are tinged with a sense of terror in their stark, deathly beauty, and their internal lighting has a theatricality that conveys an apocalyptic doom.

On the end impact wall, is a suite of animal skulls, which also take their titles from where they were found. These portraits of roadkill seemingly stare out at the viewer from empty eye cavities. They are presented on velvety dense black backgrounds, which make their details pop, and their scale is kept intimate to draw viewers in and force their engagement.

Continuing that celebration of fauna lost, another wall carries still lifes constructed of collected bones in the tradition of vanitas, that 17th century European genre of still-life painting ripe with symbolic objects intended to emphasise the transience of life and the pointless quest for power and glory. Again, these tables of plenty serve up a bleak meal of lament.

The stark honesty of the work is both a credit to the artist and his technical prowess, and his capacity to move the viewer to deeper consideration of our impact on the landscape.

Moving into the second gallery, Haddon’s exhibition is an explosion of colour and energy in contrast, but it is just as interested in how we move through, and leave a legacy upon, a landscape.

The aesthetics of Haddon’s paintings have a bit of a bower bird feel – personal references to artworks seen along his journey, histories and memories of the land passed over, and a recognition of his own migratory impact. His material use is also fluid and fleeting, moving from screen printing to spray paint, from oils and enamel, from fine detail to bold graphic gestures – constantly in search of a new expression of himself in a place.

While Haddon’s paintings make look like simple abstractions, they allow one’s eye to drift into their layers, as figures may be revealed or text float to the surface. A constant across many of the works is a pair of circles, symbolising the act of looking.

This is conveyed via the construction of a mirror mounted on a timber frame, as the viewer enters the gallery. It has a slight gallows feel, and is intended to confront us in how we view, and what we see. It feels a little at odds with the show stylistically.

The hang of work feels dense in the space, especially with so much going on visually and Haddon’s jumping between styles. This is mostly played out along the central wall of the space, where a suite of small paintings – all different – are scattered along a wall under the theme Undertow. In his essay, Haddon says they ask if memory is a form of undertow?

A self-portrait with leaves sits alongside test pattern interference paintings, a vase of flowers inspired by a painting by Gauguin, then blackened leaves in Black Bough, pulling on an Australian collective image of bushfires.

Anchoring the exhibition, is the painting On Mill’s Plains (for David Hansen) 2024, which is a stunning work that layers figurative narratives over abstracted botanical forms.

In a section called Painting, large hybrid landscapes march down a long wall and hold the room together. It’s difficult (the wanderer), It’s difficult (small portals) and It’s difficult (this Tasmanian landscape) again jump between styles, abstraction, geometry and figuration. They have a luscious glossy surface that seemingly holds their complex spatial relationships together.

Completing the exhibition is Waymaking, a cluster of small paintings on the end: The smoke was so thick, The future and the past … and smoke clouds. They have a pop feel to them in their perky palettes, text overlays and spots (aka eyes) bearing witness. The statements connect the viewer to specific moments within the landscape, both shared and very personal.

Read: Exhibition Review: Hair Pieces, Heide Museum of Modern Art

This is very capable and engaging art-making, but its discombobulation can be confusing to the viewer. More space would allow the viewer to delve deeper into the layers of the individual works, rather than be visually flung around with a horror vacui zeal. That said, that material tension is what Haddon’s work is all about.

Both these exhibitions are slick, mature and well made. There is a total knowing in their studio practice, and that comes through in the work on show. As a viewer it is totally enjoyable – you get a bit of everything at a top-drawer level – and all the while, the rigour that both these artists present in their work leaves us thinking and questioning the landscape and our engagement with it in fresh ways.

Neil Haddon, Waymarking / Painting / Undertow

David Stephenson, Bone Country

Bett Gallery, Hobart

2-24 August 2024