The Fourth of July is not only America’s birthday but a celebration of what the formation of the country represented – both independence from British rule and freedom in a broader sense.

The Founding Fathers declared the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. Today, we are still striving for those ideals, whether in small moments of peace or big moments of change. As we think about the meaning of Independence Day, we turned to artists for their interpretations.

Here are five works on display in Maine, selected by their respective museums as representations of freedom.

Arnold J. Kemp (b. 1968). “Stage,” 2023. Maple plywood. Courtesy of the artist and Martos Gallery, New York. Photo courtesy of Dave Clough

“Stage,” by Arnold J. Kemp

Center for Maine Contemporary Art, Rockland

“I would survive. I could survive. I should survive.”

That phrase is writ large, the letters cut in wood and collapsed on top of each other. The sculpture makes Ashley Page feel somber.

“It forces you to think about the reason why somebody had to make a work like that,” she said. “This is a very simple phrase. ‘I would survive. I could survive. I should survive.’ But it’s still a question; it’s still something that isn’t permanent or guaranteed. It feels very somber to me in that we’re all still fighting this fight. As an African American, as a Black person, we still have to enforce our value in this society.”

“Stage” is part of “To Whom Keeps a Record,” a solo exhibition for Arnold J. Kemp at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockland. Kemp is based in Chicago and is the 2023 Ellis-Beauregard Foundation Visual Arts Fellow. The show features three monumental works, including a compilation of 52 photographs of texts from his personal library (“Possible Bibliography”) and a sculpture in which visitors can interact with his vinyl collection (“Music Brings Goodness to Us All Unless One Has Some Other Motive for Its Use”).

Page, a multidisciplinary artist based in Portland who was the guest curator for the exhibition, described the exhibition as an intimate snapshot of the artist’s work.

The poem that became “Stage” started as a handwritten note in the artist’s studio. This piece is born from the present day. Page noted that Kemp made it after the COVID-19 pandemic, after the murder of George Floyd. It is a prompt to imagine a world in which this phrase would be a given.

“It feels like a call for freedom,” Page said. “It feels like a step in that direction. It feels like a reinforcement of the need for liberation.”

“It’s a call to create a better world in which this work is not necessary.”

“To Whom Keeps a Record” is on view until Sept. 8. Summer hours at the CMCA are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Monday through Saturday and noon to 5 p.m. Sunday. For more information, visit cmcanow.org, or call 207-701-5005.

“Sunbather,” Lucia Taylor Miller (1928-2019). Terra cotta, 8-by-9-by-17 inches. Monhegan Museum of Art & History, Gift of Lucia Taylor Miller. Photo courtesy of Monhegan Museum of Art and History

“Sunbather,” by Lucia Taylor Miller

Monhegan Museum of Art and History

Laura Desmond sees a woman “utterly and completely herself.”

“This figure is unselfconscious and unguarded in her embrace of the sun and of her own body,” Desmond wrote about this piece. “The artist emphasizes the solidity of this figure’s flesh, from her rounded arms to her expansive thighs, accentuated by the chunkiness of the terracotta, even as the warmth of the terracotta calls to mind the warmth of sun on naked flesh. This is a body serving its own purposes. She is literally embracing herself, her right arm resting on her chest, so that she is simultaneously touching and being touched.”

Desmond is the assistant curator at the Monhegan Museum of Art and History, and “Sunbather” is part of this summer’s exhibition at the museum to celebrate the Women Artists of Monhegan Island. The group formed in the mid-1980s and aimed to increase opportunities for women to show their work on and off the island. Among them was Lucia Taylor Miller, who died in 2019. She lived in the Midwest but started visiting Monhegan with her family when she was 5 years old and returned later in life, starting in 1995. She became a member of the Women Artists of Monhegan Island in the early 2000s.

Desmond said she is drawn to this piece because the artist rejects the objectification of the female body.

“This figure is not a vessel for the viewer’s desire, but is ordinary flesh, solid, and existing for its own sake,” she said. “This is an achievement of Miller’s creative process; I like to imagine the series of choices that she made with her materials, as she shaped and molded each and every curve and fold of the sunbather’s body. The intimacy of the sculptor with her subject yielded a very intimate sculpture, one that is deeply human and relatable. I suppose you could say that the sense of freedom generated by this sculpture is a product of the freedom of the artist’s process.”

“A Common Bond: Women Artists of Monhegan Island” features 16 artists who were longtime members of the group, and the catalogue includes reproductions of work by all former members, including those who are still practicing artists today. The exhibition is on view until Sept. 30. The Monhegan Museum of Art and History is open from 11:30 a.m. to 3:30 p.m. daily in July and August and 1:30-3:30 p.m. in September. For more information, visit monheganmuseum.org, or call 207-596-7003.

David C. Driskell (United States, 1931–2020), Ghetto Wall #2, 1970, oil, acrylic, and collage on linen, 60-by-50 inches. Portland Museum of Art, Maine. Museum purchase with support from the Friends of the Collection, 2019.16. © Estate of David C. Driskell. Image courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York

“Ghetto Wall #2,” by David Driskell

Portland Museum of Art

A brick wall situates this painting in an urban landscape, and it reminds Shalini Le Gall of one she knows well.

“I love looking at that lower quarter of brick because it feels like Portland,” she said. “There’s ways in which that aesthetic is very much part of the aesthetic around us.”

Le Gall, chief curator at the Portland Museum of Art, described this painting as “an icon” of the collection. David Driskell was a prominent artist and scholar who was instrumental in bringing recognition to African American art as part of the history of American art. He first came to Maine in 1953 to study at the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture and lived part time in the state for many years until his death in 2020 at age 88. He made “Ghetto Wall #2” in 1970.

“This is David really at the moment of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States, reacting to that and thinking about painting as a way to become part of that dialogue of, how do you visually capture this incredible moment in American history in which we are thinking deeply about what it means to continue Black liberation,” Le Gall said.

This painting is more than 50 years old, but Le Gall said the symbols and the struggle in it feel current.

“It’s that dark and shadowed figure that for me makes this work very powerful when you see it in person,” she said. “It’s also quite large. It’s 60 by 50 inches, almost 5 feet going up. When you’re standing in front of that figure, there is a sense of introspection that is inspired. It’s not an abstract notion of freedom or of American symbolism or of urban identity. It’s one that immediately takes you to your personal, subjective space. How do I feel about these symbols? How do I feel about what’s presented here?”

“Ghetto Wall #2” is on view at the Portland Museum of Art, which is open from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. Wednesday through Sunday. On Fridays, the museum stays open until 8 p.m. For more information, visit portlandmuseum.org, or call 207-775-6148.

Channing Hare, “Portrait of a Woman,” 1945, Oil on canvas, 34-by-31 inches, Museum Purchase, 2010.27. Image courtesy of Ogunquit Museum of American Art

“Portrait of a Woman,” by Channing Hare

Ogunquit Museum of American Art

Channing Hare built a reputation in the first half of the 20th century as a realist painter of socialites who frequented Palm Beach, Florida, and Ogunquit. He attracted high-profile commissions and commanded expensive fees for the time. But he also often painted his more personal works in the surrealist style, including “Portrait of a Woman” in 1945.

“It’s such a hard divide,” Devon Zimmerman said, between one body of work and the other.

Zimmerman, curator of modern and contemporary art at the Ogunquit Museum of American Art, said the surrealist paintings such as this one hint at a world where Hare was free to express his identity as a gay man during a time when doing so came with great risk. When Zimmerman reorganized the museum’s permanent collection, he was fascinated by the way many marginalized artists turned to magical realism in their work in the early 20th century. This piece is now installed alongside others in that same vein.

“Those narratives start to percolate out as to when the realities of the world do not present the freedom that one is warranted or a freedom that is accessible,” Zimmerman said. “Sometimes the most subversive thing to do is to create a space where one can create that freedom.”

“Portrait of a Woman” is haunting – a mannequin holds her head in her hand as her fabric flesh decays. Zimmerman said the rich fabric and ornate chair are likely a reference to Hare’s passion for the decorative arts and his relationship with another man, with whom he ran a high-end shop on Ogunquit. But the mystery of the painting is also on purpose.

“It poses all of these questions that don’t offer much in the way of answers,” he said. “In its strangeness, it leaves space for slippage or misunderstanding or unknowing. That vertigo of unknowing is a productive and freeing space where there will not be an answer.”

“Portrait of a Woman” is on view as part of “Networks of Modernism: 1898-1968” until the museum closes for the season on Nov. 17. It is open every day from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. For more information, visit ogunquitmuseum.org, or call 207-646-4909.

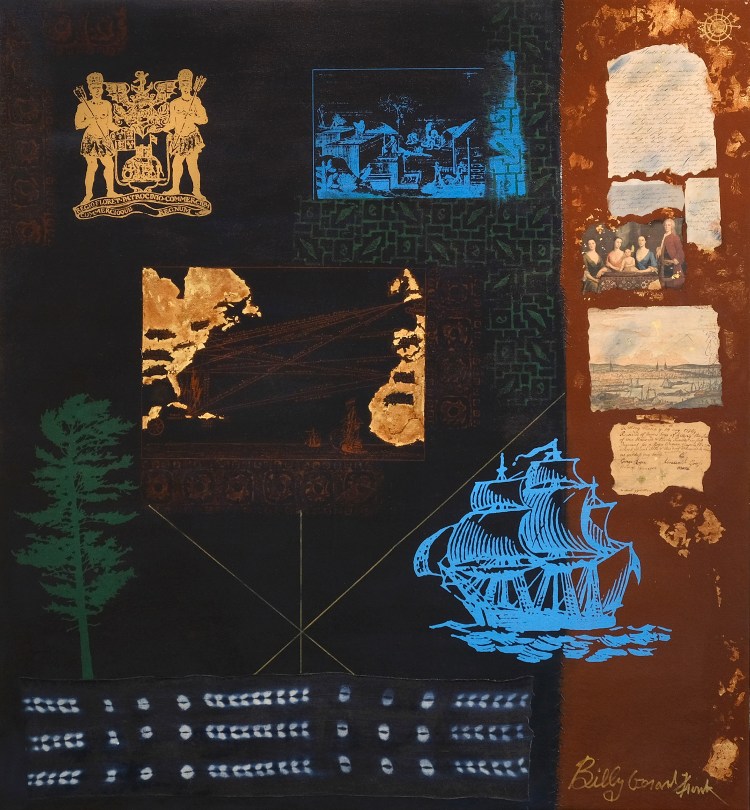

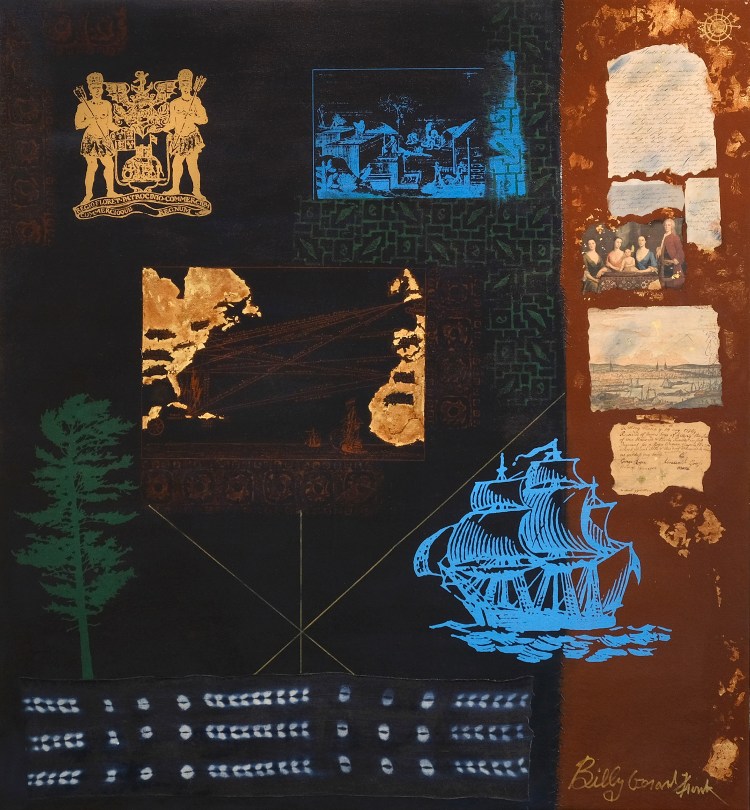

Billy Gérard Frank (b. 1970), “Indigo: Entanglements, No. 5,” 2022, silkscreen, natural pigments, vintage African fabric, newsprint, and acrylic. 62-by-70 in. Museum purchase supported by an anonymous Maine donor, 2022.34. Image courtesy of Billy Gérard Frank

“Indigo: Entanglements, No. 5,” by Billy Gérard Frank

Farnsworth Museum, Rockland

The family in the upper right of this portrait is the Royall family painted by Robert Feke in 1741.

Isaac Royall was born in Maine in 1672 and moved with his family to Massachusetts as a toddler. At 28, he established a sugar cane plantation on the island of Antigua, which he later passed on to his son.

“Indigo: Entanglements, No. 5″ is part of a new and ongoing series by artist Billy Gérard Frank in collaboration with Portland printmaker David Wolfe that examines the roots of the transatlantic slave trade. The works incorporate archival materials such as the portrait of the Royall family, as well as maps, text and fabric. The artist has described his work in this way: “I mine and contest, images, symbols, text, and collective memories culled from histories, exploring the human complexity and drama of the slave trade and colonialism.”

“I’m compelled by Frank’s artistic practice as a kind of storytelling that weaves together complex narratives,” Francesca Soriano, associate curator of American art at the Farnsworth, wrote. ” ‘Indigo: Entanglements, No. 5’ in particular addresses Maine’s role in slavery. For instance, the ship and pine tree in the lower half of the composition reference the timber industry used to build boats to transport enslaved people across the Atlantic.”

Soriano noted the other references in the silkscreen: the logo of the Royal African Company, a mercantile company established in 1660; a map of the “Triangle Trade” between Britain, its American colonies and Africa. She said the piece reflects the struggle for freedom by those who were enslaved in this country.

“These visuals offer direct links to Maine’s (and greater New England’s) financial connection to the Atlantic slave trade. I think it’s important that as a Maine institution, we acknowledge this entangled history of our state. With ‘Indigo: Entanglements, No. 5’ we have a way of opening up that conversation.”

“Indigo: Entanglements, No. 5” is on view in the permanent collection at the Farnsworth. Summer hours at the museum are 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. daily. For more information, visit farnsworthmuseum.org, or call 207-596-6457.

Related Stories