Ashley Page inside the kitchen at the Tate House. Page’s installation of vinyl banners and assemblages at the 1755 home, titled “Imagining Freedom,” was inspired by the life of Bet, who worked inside of the home as an enslaved servant. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

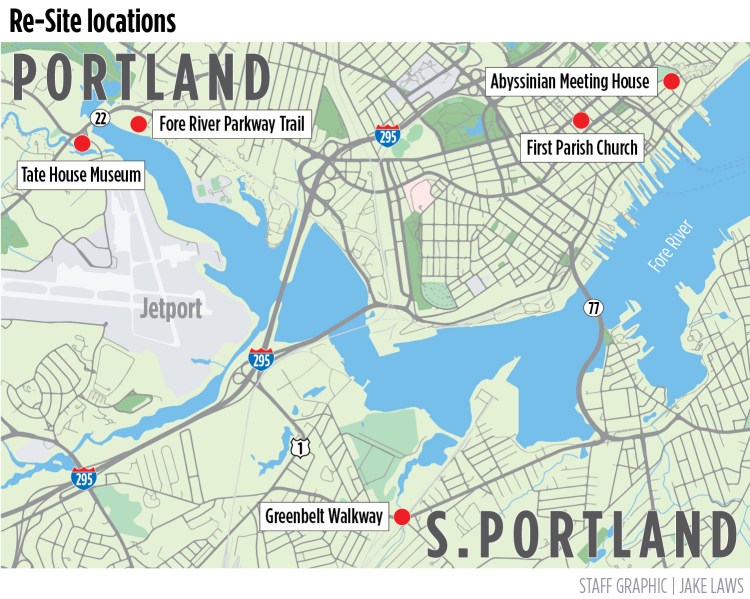

First Parish Church. The Abyssinian Meeting House. Tate House Museum.

Any local history buff would know those sites in Portland. But Space in Portland is offering aficionados and novices alike the opportunity to see them anew. In an ongoing project called Re-Site, the nonprofit asked five local artists to create temporary public art installations that offer new interpretations of these sites and others integral to the city’s past.

“Art is a really great vehicle to use for telling these stories because I think it recontextualizes it, it explains it in a different way that can bring people in,” said Meg Hahn, development and special projects manager at Space. “The idea of highlighting stories from the past and then combining that with contemporary artists using contemporary methods, I think is an interesting juxtaposition.”

This year brings the second iteration of Re-Site. Space first presented the project in 2020, when the organization was focused on outdoor programming during the COVID-19 pandemic. The artists who participated then nominated the five who contributed this year. The resulting projects are all different, located both indoors and outdoors, ranging from an orchestral audio composition to sculptures meant to be eaten by birds to photography.

Seth Goldstein, director of Cushing’s Point Museum and director of development at South Portland Historical Society, and Libby Bischof, executive director of Osher Map Library and Smith Center for Cartographic Education and professor of history and university historian at University of Southern Maine, provided research on each site. The artists also worked closely with the stewards of their chosen locations in Portland and South Portland.

One of those hosts is Holly K. Hurd, executive director of the Tate House Museum, who described the work installed there by Portland artist Ashley Page as “profound.” The 18th-century house museum on Westbrook Street has been in recent years including more information and objects about a Black woman who was likely enslaved by the home’s white owners in colonial times. But Hurd said Page went beyond the meager documentation that exists about Bet to give her more dimension.

“Ashley is imagining what it may have been like for Bet,” Hurd said. “The historical records only go so far, but art is such a powerful way to bring those things forward.”

Here are the five artists and their chosen sites:

ASHLEY PAGE, “IMAGINING FREEDOM”

Tate House Museum, 1267 Westbrook St., Portland

Ashley Page lives in Portland but had never been to the Tate House Museum before she started working on “Imagining Freedom.”

“I had a good sense of the larger scale and scope of what Maine’s history looked like,” Page said. “But to be able to dive deeper into one individual, one family, that provided a much more personal and deeper lens.”

In recent years, the museum has shared more information with visitors about an enslaved woman named Bet, such as what kind of work she might have done and where she might have slept. But Page wondered more about the person than the labor. She focused her work around a question: “What did freedom look like for Bet? What did her daydreams look like, sound like, taste like?”

“I wanted to humanize her story and her life,” said Page, 25. “I started to do a lot of research around where she might have come from, what she would feel nostalgic about, what she would have liked to eat, where in her day-to-day life she might have found moments of respite or peace or comfort.”

She made seven banners that are currently placed throughout the house and its grounds. They are dreamlike, made in shades of blue and white and gray, inspired by the past and also the future. They reference both the lavender that would have grown in the garden and the palm trees that Bet might have known in the Caribbean. She also made an audio piece that includes sounds from nature, the words of James Baldwin, an improvisational jazz set.

“Black history is everywhere,” she said. “It is in the cloth that we wear. It is in the cars that we drive. It is in the food that we eat. It is in the waters that we drink. It’s in the oceans that we swim in. For me, it is always at the forefront of my brain.”

Page’s work will be on view at least through June 30. The Tate House Museum is open Wednesday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tours start on the hour, with the last tour beginning at 3 p.m. Admission is $16 for adults, $14 for seniors, $8 for children ages 6-12 and free for those under 6. June 19 will be a Juneteenth Community Day, with free admission and a cyanotype workshop by Page.

For more information, visit tatehouse.org or call the museum at 207-774-6177.

“Aggregate” is the name of Rachel Alexandrou’s art installation at Fore River Parkway Trail. Sofia Aldinio/Staff Photographer

RACHEL ALEXANDROU, “AGGREGATE”

Fore River Parkway Trail, Hobart Street, Portland

Rachel Alexandrou made her project with both human and avian visitors at the Fore River Parkway Trail in mind. She is a longtime forager and studied horticulture at the University of Maine, and now she uses her education in plant science to make art about food and land.

“I love being able to engage people’s senses, especially using foraged food,” she said. “There’s a lot of strange, unusual flavors. Some of the things they are eating, they didn’t even know were possible to eat.”

Alexandrou partnered with artist Joshua Clukey, who works with local clay, to explore the ecological and geological history of this area. The Portland Brick Company once sat on the banks of the Fore River. Alexandrou described the manufacturer as “a ghost in time” because few records exist about its work, but the artists did find brick chips and discard on the land.

For her part, Alexandrou crafted temporary wildflower brick sculptures on the site; the herbaceous seeds inside are native to the site. She’s also making two meals – one for birds and another for people. For “Cake for Birds,” she is making a mix for birds that contains wild seeds and fruits, and guests are invited to the birdwatching event with the artist. For “Feast for Humans,” which is sold out, she is making dishes from foraged ingredients that have long grown in the area and also invasive plants such as Japanese knotweed that have taken root here. Clukey is using local clay to make the plates for that event.

Alexandrou, who lives in Waldoboro, said she is concerned that many people do not know much about the complexity of the natural world and the many varieties of plants that grow there.

“I’m introducing people back to plants through food,” said Alexandrou, 37. “Food is a great vehicle for getting people interested in plants. It’s a little way for them to remember it. Once you’ve smelled something or tasted it, that memory is fixed in your brain.”

“Cake for Birds” is on June 3 from 5-8 a.m. and 6-8 p.m. No RSVP required. For more information, visit space538.org.

Artist Ling-Wen Tsai will install 850 wooden stakes near the Greenbelt Walkway in South Portland to signify the diversity of marine species in the Casco Bay Estuary. The project, “Ahead of Schedule,” is depicted here in a concept drawing. Image courtesy of the artist

LING-WEN TSAI, “AHEAD OF SCHEDULE”

Greenbelt Walkway, Broadway and Clemons Street, South Portland

Ling-Wen Tsai found her location for Re-Site along one of her regular walking paths in South Portland. The Greenbelt Walkway passes a teeming salt marsh that abuts a grocery store, a busy parking lot and local roads.

“The Hannaford parking lot as a background and the birds in front of it, that relationship was really interesting to me,” she said. “That site is located in a kind of tension.”

As an interdisciplinary artist, Tsai is interested in using her work to create space “that allows us to escape an overwhelming world we live in and provide a sense of peace,” she said. There, she hopes that people are able to find contemplation that isn’t possible amid the demands of everyday life.

The project she will install near the Greenbelt Walkway later in June invites people to contemplate the impacts of climate change. She will place 850 wooden stakes painted with environmentally friendly milk paint that will illustrate the predicted sea level rise in this area.

“The 850 stakes are representing 850 different species of marine life in the Casco Bay estuary,” she said. “Casco Bay has a really amazing diverse and rich ecosystem, so we really need to treasure that. I want people to think, ‘Whoa, there’s 850 different species living here. We really need to be more mindful on protecting this cove.’ ”

The project will open with a guided site walk to discuss the history of the cove and how its development has impacted the natural landscape. Mill Creek was once home to a tidewater mill, which allowed settlers to grind their corn to flour but also disrupted fish migration and Indigenous food sources. It was completely destroyed by fire in 1892.

“You are just really able to see how the humans are changing the shape of the cove,” she said.

Register for the site walk on June 22 from 11 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. at space538.org.

James Allister Sprang makes audio-visual projects that celebrate the sensory experience of Black life. He was one of five artists who made art for Re-Site, a project about local history and art hosted by Space Gallery. His site was the Abyssinian Meeting House, and he held three listening sessions there in May for audio pieces he created. Here, he’s behind the Abyssinian in Portland. Michele McDonald/Staff Editor

JAMES ALLISTER SPRANG, “LISTENING SESSIONS”

Abyssinian Meeting House, 73 Newbury St., Portland

James Allister Sprang moved to Maine a year and a half ago and quickly noticed the Abyssinian on walks in his neighborhood. He got curious about the third-oldest African American meetinghouse in the nation. So when Space approached him about Re-Site, he knew exactly where he wanted to focus his project.

Sprang, who splits his time between Portland and Philadelphia, describes his work as “audio-visual projects that celebrate the sensory experience of Black life.” In May, he hosted listening sessions at the Abyssinian of three different sound compositions, and the last work in particular – “Rest Within The Wake” – had a deep connection to the place. It is an orchestral piece written for 17 instruments.

“I wrote it while learning how to dive, thinking about the depths of the ocean and that space’s relationships to the transatlantic slave trade, that space’s relationship to Black bodies,” he said. “It was wonderful to play that piece inside of the Abyssinian Meeting House.”

The participants laid on mats on the ground and did breathing exercises as they listened to “Rest Within The Wake.”

James Allister Sprang stands in the Abyssinian Meeting House at the front of “Listening Sessions #1: Aquifer of the Ducts,” a 40-minute soundscape of layered tape recordings and modulated synths. Photo courtesy of Space

Sprang said he thought about the people who built the meeting house and found community there, many of whom worked on the water. In 1898, 19 crew members who attended the Abyssinian died when the SS Portland sunk on a return trip from Boston, a significant blow to the congregation.

“When you’re lying on the floor, you’re looking up at the exposed rafters, exposed beams in the ceiling, and it’s extremely reminiscent of the hull of a ship,” Sprang said. “Looking up at this wooden structure, hearing the resonance of the space and listening to these orchestral swells that were composed to emulate the flowing wages, it felt moving.”

The listening sessions are over, but a 10-minute excerpt of “Rest Within The Wake” is available on Sprang’s website (jamesallistersprang.com), and the full composition is also available for purchase.

MAYA TIHTIYAS ATTEAN, “ROOTS OF RESILIENCE: ECHOES OF CONNECTION”

First Parish Church, 425 Congress St., Portland

Maya Tihtiyas Attean first heard the story from her mother. In 1757, Rev. Thomas Smith of the First Parish Church helped orchestrate and support an expedition to hunt and kill Wabanaki people in exchange for money.

“There’s a plaque inside that’s dedicated to this man who did this,” Attean, 30, said of the prominent Portland church. “I feel like it’s very important to show the other side of this history. Yes, this church isn’t who this guy is, but they have certainly benefited from the violence that happened.”

Attean is a Wabanaki artist who works primarily in photography, and she is interested, in part, in creating images that manipulate reality. She often works in more traditional methods, such as developing film in a dark room, because she wants to reclaim a tool that has been used to marginalize Indigenous people for many years.

Maya Tihtiyas Attean made “Roots of Resilience: Echoes of Connection,” three digitally collaged photographic vinyl banners displayed on the side of First Parish Church in Portland in May. Photo courtesy of Space

At First Parish Church, she created three large panels that were displayed through the end of May on the exterior wall of the building. The images were collages of trees, paired with a sound composition Attean made from archival video recordings her mother made of Wabanaki children in the 1990s and the sound of a women’s traditional chant that she loves. The artist also used the piece to shed light on Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Awareness Day on May 5.

“The trees represent the connections that we have as Indigenous people through one another,” she said. “I wanted to represent the resilient spirit that my ancestors had to survive through these challenging times in 1757 to today.”

Attean said the church today still has much to learn and is generally disconnected from tribal communities, but she found people there who want to make amends with Wabanaki people.

“We’re often forgotten when it comes to talking about people in Maine as a whole,” she said. “We don’t have a lot of sovereignty in government. I hope that people interacting with this piece are reminded of the consistent struggle and attempt at our own sovereignty and survival, and how we use our culture to push through these times and connect with one another. I hope that people can be more aware of Wabanaki people as a whole.”

Attean posted the audio composition as a link

on her Instagram profile @mayatihtiyasart.

Related Stories

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

Use the form below to reset your password. When you’ve submitted your account email, we will send an email with a reset code.